The following is an excerpt from Hothouse: The Art of Survival and the Survival of Art at America’s Most Celebrated Publishing House, Farrar, Straus and Giroux by Boris Kachka, out now from Simon and Schuster.

Among those New Yorkers who made ad hoc plans on Sept. 11, 2001, driven together by emergency and grief, were novelists Jonathan Franzen and Jeffrey Eugenides. They’d been introduced a few years back by their mutual editor, Jonathan Galassi, at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Franzen had an apartment on the Upper East Side. Eugenides lived in Berlin but happened to be staying in the West Village; he was marooned uptown that day, so Franzen offered to put him up. They met on the steps of the New York Public Library, tromped together through streets stunned into silence, found an anonymous Italian restaurant, and commiserated over a changed world.

“Who would have guessed that everything could end so suddenly on a pretty Tuesday morning,” Franzen wrote in the next issue of The New Yorker. “In the space of two hours, we left behind a happy era of Game Boy economics and trophy houses and entered a world of fear and vengeance.” What Franzen couldn’t foresee, but privately hoped, was that America would still need relics of that more complacent age. Few of that autumn’s artifacts would survive the leap from one era to another. There was really only one novel that did, a book that had been out for six days: The Corrections.

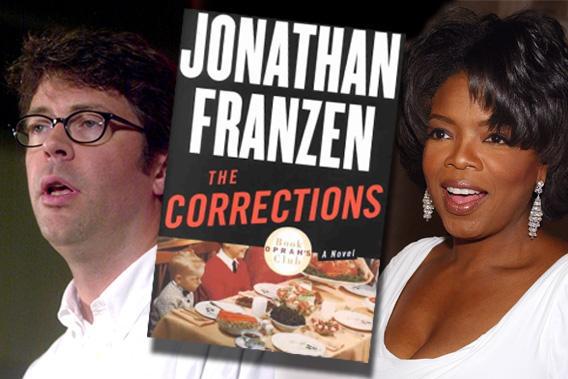

Farrar, Straus and Giroux was the relic of an even earlier era, one abounding with wealthy patron-operators like Roger Straus. The brash and haughty Guggenheim heir had sold FSG to a German conglomerate in 1994; seven years later, at 84, he was still its president. The Corrections helped deliver both writer and publisher into a century with a new set of rules. They had some surprising help, and more than a little grief, from a talk show hostess named Oprah Winfrey.

The Friday before Labor Day, 11 days earlier, was perhaps the year’s slowest day at FSG’s Union Square headquarters. Lynn Buckley, who’d designed the book jacket for The Corrections, happened to be among the very few people still in the office. So was Peter Miller, Franzen’s publicist. Early in the afternoon, he called out to her suddenly from his office across the hall. “Oh my god, you won’t believe it,” he shouted. “The most amazing thing that ever happened for a book just happened for The Corrections!”

“What happened?” Buckley asked, “Did it win the Pulitzer Prize?”

“No,” he said, “It’s an Oprah selection!” The Corrections was the 45th pick of Oprah’s Book Club, but it was among only a handful chosen right on publication. “I guess it helps a book sell more than a Pulitzer, right?” Buckley says now. “That just seems crazy to me.”

Franzen felt much the same way. Around lunchtime, someone called him at home and told him to expect a call from the New York Times in 45 minutes. Would he be home? Sure, he said, befuddled by the cloak-and-dagger routine from a paper he’d already written for. Actually, it was Harpo, Oprah’s company, securing the line as though it were one of Roger Straus’s ancient CIA contacts. “Everything was bogus from the start,” Franzen says. “My first encounter with Harpo Productions was being told a lie.” Here’s how he remembers the ensuing phone conversation:

“Jonathan?”

“Yes?”

“Oprah Winfrey!”

“Oh. Hi. I recognize your voice from TV.”

Awkward silence; deep breath from Oprah.

“Jonathan, I love your book, and we’re going to make it our choice for the next book club!”

“That’s really great—my publisher’s gonna be really happy,” he said in an even tone. They hung up soon after.

“I think she was surprised that I wasn’t moaning with shock and pleasure,” Franzen says now, a decade later, even after a very public show of reconciliation. “I’d been working nine years on the book and FSG had spent a year trying to make a best-seller of it. It was our thing. She was an interloper, coming late, and with an expectation of slavish gratitude and devotion for the favor she was bestowing.”

Franzen promptly went up to Tarrytown, N.Y., to play tennis with his friend, the writer David Means. Though sworn to secrecy, he told Means about Oprah and they had a few drinks to celebrate. Having only recently bought a cellphone, Franzen wasn’t yet accustomed to checking his voice mail. On the train back into the city, he discovered he had seven messages from Peter Miller.

Back at FSG, Miller had been faxed a long contract from Harpo, which covered timing, media coordination, and the important issue of where and how to display the Oprah logo on the cover. The contract had to be signed by midnight Chicago time, or 1 a.m. Eastern, in the wee hours of Labor Day weekend—a bizarrely inconvenient deadline. Roger Straus and publisher Jonathan Galassi were out of town, publicity chief Jeff Seroy in the Pyrenees. Spenser Lee, the director of sales, had left for the day but lived nearby. He came in to sign in Galassi’s place. But no one could sign for Franzen.

The author’s train rolled into the Harlem Metro-North station around 11; he and Miller and Buckley met up shortly afterward in Franzen’s rent-stabilized Upper East Side one-bedroom. With 90 minutes to spare, they sat around a kitchen table and perused the contract. Buckley had brought along a copy of what they called Oprah’s “poker chip,” and they tried placing it over different parts of Buckley’s cover. Nothing seemed right. Could they put it on the back? Franzen asked. Per the contract, they could not.

“Jonathan started talking out loud,” Miller remembers. “Saying, ‘Why should I do this?’ And of course I, being the representative of the publicity department, said, ‘This is an enormous opportunity.’ ” Franzen says he never seriously balked. “FSG had stuck with me through a book that hadn’t done well, and had been very patient, and I love what they mean to American literature. The idea that this was going to add instantly another half million to their sales—there’s no way I wasn’t gonna do it for them.” What about for him? “Having gotten there with my own steam, I felt a certain resistance to the boost that [it] would represent.”

The world would soon know about Franzen’s ambivalence. But for the moment, as the trio walked briskly to a nearby Kinko’s to fax the contract just ahead of the deadline, those doubts were tossed hurriedly aside. On the way, Franzen muttered, half to himself, “I just realized I’m probably a millionaire.”

On Sept. 9, The Corrections made the cover of the New York Times Book Review. Inside, David Gates raved about “Jonathan Franzen’s marvelous new novel.” It had conventional appeal, but “just enough novel-of-paranoia touches so Oprah won’t assign it and ruin Franzen’s street cred.” In fact, Oprah was set to assign it four days later. That announcement was postponed in the wake of the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil.

FSG had drawn up a packed schedule for Franzen’s rollout, beginning with a Sept. 18 launch party on the roof of a SoHo hotel. Returning to work on the 13, PR head Jeff Seroy struck a defiant pose. “Fuck them,” he told Roger Straus, “we should just carry on!” Roger, soon to resign as president, responded with one of his last judgment calls: “Are you out of your mind? You want to have everyone at this party standing there staring at the wisps of smoke rising from the ruins of the World Trade Center?” The party was postponed for a month.

Oddly, Sept. 11 seems to have helped The Corrections. Oprah’s postponement gave FSG some extra time to print an additional 680,000 copies. By the time she did officially announce her selection, many stores had already gotten books bearing the Oprah logo, exploding her embargo but building buzz. “A work of art and sheer genius,” Oprah finally told her viewers on Sept. 24. “When critics refer to the great American novel, I think, this is it, people!”

The day of the announcement, Franzen was well into a successful book tour—passing through stringent but sparse security lines, stretching out over empty airplane rows, driving to packed readings. “People were sick of staying home and watching TV,” he says. “It was a total embarrassment of riches … I think one of the main reasons that the entire world turned on me during the Oprah thing was that one person had benefited from 9/11, and that was me.”

He gave the world plenty of ammunition. In regional interviews, his ambivalence pushed its way out into the open. “That Oprah selection will probably not sit well with the writers I hang out with and the readers who have been my core audience,” he told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He confessed to the Miami Herald that he was “muddled” about the Oprah pick—especially the logo’s “corporate branding.”

Finally, a story in the Portland Oregonian foregrounded his reservations: “Oprah’s Stamp of Approval Rubs Writer in Conflicted Ways.” He’d told them the pick did as much for Oprah—hitching her to the “high-art literary tradition”—as it did for him. On Oct. 12, the day the story ran, Oprah put in a call to Union Square. Peter Miller answered. The first thing she said was, “What is this guy’s problem?” She went on to say she might cancel Franzen’s appearance.

“I felt like I was getting an ulcer,” Miller says. “I was terrified that this was going to sink the ship.” Beyond The Corrections, Oprah might blame FSG for the mess, jeopardizing their long-term relationship with the arbiter of America’s reading taste. Would she ever take another chance on the publisher that had burned her?

Miller passed Winfrey on to Seroy, who tried to explain that she’d caught Franzen on “a very steep learning curve,” having “spent 10 years in a cave writing this book.” But he didn’t quite apologize for his author. “[Franzen] was kind of clumsy, or unpracticed, or graceless in the situation,” Seroy says. “I don’t know whether I would call it a mistake.”

That evening, after his final New York reading, Franzen dined with Miller, Seroy, and his agent. “We all yelled at him,” Miller says. “’How could you sabotage it?!’” But it was Galassi’s dressing down that Franzen remembers most. “He said, ‘You’ve outgrown this,’” Franzen remembers. “He was essentially saying, There’s no need for you to be so angry anymore. You have a chance to reach lots of people. Don’t alienate them.”

At FSG’s behest, Franzen wrote Oprah a personal letter of apology. In public, he offered grudging semi-apologies that, by blending false abjection with unfortunate flashes of honesty, occasionally made things worse. “To find myself being in the position of giving offense to someone who’s a hero — not a hero of mine per se, but a hero in general — I feel bad in a public-spirited way,” he told USA Today.

On Oct. 23, five days after Franzen finally had his rooftop party, the news was all about anthrax in the White House mail facility. But FSG fixated only on one devastating public statement: “Jonathan Franzen will not be on the Oprah Winfrey show, because he is seemingly uncomfortable and conflicted about being chosen as a book club selection.” Mercifully, the dreaded corporate “poker chip” stayed.

It’s possible that airing the show would have sent The Corrections into the stratosphere, but the controversy did boost sales by at least 150,000 copies. With more publicity to do, Seroy hired a media coach to teach Franzen to love the idiot box. “I prefer it to print interviews,” he says now. Oprah, too, was chastened. After a one-year book-club hiatus, she mostly stuck to classics. Her first new selection after The Corrections, in 2005, was James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces. After that didn’t go so well either, she went back to classics yet again. The first one she picked was Elie Wiesel’s Night. It happened to be on the backlist of an FSG subsidiary, setting up another great year for Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

—

Excerpted from Hothouse: The Art of Survival and the Survival of Art at America’s Most Celebrated Publishing House, Farrar, Straus and Giroux by Boris Kachka, out now from Simon and Schuster.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.