This essay is adapted from Ed Park’s introduction to the new edition of Russell Hoban’s novel Turtle Diary, out now from New York Review Books.

You hear a lot about things you’re supposed to read. My own shelves are crammed with books I mean to get around to sometime. Yours probably are, too. So you may think you don’t have room for Russell Hoban’s novel Turtle Diary, which comes swimming back into print after nearly four decades, as patiently as its titular reptiles traverse the oceans stroke by miraculous stroke: “Thousands of miles in their speechless eyes, submarine skies in their flipper-wings.”

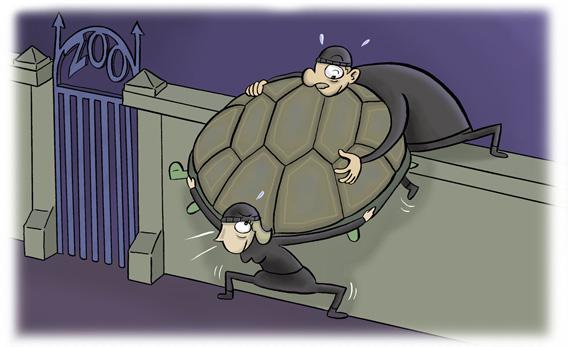

This is what the best books do. They have all the time in the world. They never get lost. They find their way to you. What if I told you that Turtle Diary, about two loners on a mission to liberate the sea turtles from the London Zoo, is like a lot of things you already like, while being so much its own stupendous thing, that it’s become one of my literary yardsticks?

For Turtle Diary is a disquisition on loneliness as perfect and inexhaustible as the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” or Chekhov’s “Lady with the Little Dog,” a work of art that vibrates on a new frequency each time you read it, depending on the weather in your life. Like Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, it’s a breathtaking lattice of metaphors, everything standing for everything else, and on every page, the inventive similes—like those of P. G. Wodehouse, J. G. Ballard—provide a steady stream of delight. Birds called oyster-catchers “walked with their heads down, looking as if they had hands clasped behind their backs like little European philosophers in yachting gear.” Though its “he wrote, she wrote” chapters don’t crescendo into the blood-curdling shriek of Gillian Flynn’s ingenious thriller Gone Girl (or, for that matter, the crazed fan letter/late reply of Eminem’s “Stan”), the alternating POV generates a beautiful urgency here. And like Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, it’s the most emotionally direct (and, to my mind, finest) novel by a writer whose other remarkable books tend to resemble trips down the rabbit hole.

Turtle Diary is one of the great novels of middle age. Those of you not yet at that nebulous stage of life (as I wasn’t, when I first read it), those of you comfortably or uncomfortably past it, don’t shut the cover yet. It’s a book that can help you, even if you don’t think you need help. (If you’ve read this far, you do.) It offers solace to anyone who has ever looked at her situation in life and wondered, as one of Hoban’s characters does, “Am I doomed?” (Answer: No.)

I’m going to make you need this story, do a better job of it than the one done by bookstore clerk William G., the first of the novel’s two fortysomething diarists.

“Today one of those women who never know titles came into the shop. … This one wanted a novel, ‘something for a good read at the cottage.’ I offered her Procurer to the King by Fallopia Bothways. Going like a bomb with the menopausal set.

She gasped, and I realized I’d actually spoken the thought aloud: ‘Going like a bomb with the menopausal set.’

She went quite red. ‘What did you say?’ she said.

’Going like a bomb, it’s the best she’s written yet,’ I said, and looked very dim.”

In Turtle Diary, the inside slips outside, the private turns public. What ensues is often embarrassment, fumbling, and regret, but also a rekindled sense of life and emphatic, even amazing action. “I’ve precipitated a harmless fantasy into an active crisis,” worries Neaera H., Hoban’s other diarist, once she and William have decided, nearly wordlessly, to launch the turtles out of their tanks and over hundreds of miles back to the sea.

Neaera has a public face—she’s a successful children’s-book writer and artist—but she’s as mummified by loneliness as William is. “My married friends wear Laura Ashley dresses and in their houses are grainy photographs of them barefoot on Continental beaches with their naked children,” she wryly observes. “I live alone, wear odds and ends, I have resisted vegetarianism and I don’t keep cats.” But what friends? We never meet any of them. Interacting with one of William’s coworkers, she notes, “I could feel my face not knowing what to do with itself.”

She describes herself as “a more or less arty-intellectual-looking lady of forty-three,” who “looks, I think, like a man’s woman and hasn’t got a man.” When William, a divorcé, first sees her in the bookshop (an event that doesn’t happen till Page 45), he pegs her as an “arty-intellectual type about my age or a little younger. … Not at all bad-looking.” But when she asks for a book about turtles, he feels a sort of magnetic repulsion: “I don’t really want to talk to a woman who’s accumulated the sort of things in her head that I have in mine.” Look at all the lonely people.

It takes more entries still before these two skeptical, cautious souls establish, almost telepathically, that they’ve both been fixated on the captive turtles. (“Had I in fact said it? That first day at lunch I’d talked in code, talked about hauling bananas. Had I ever said turtles?”) They join forces, and both lives change. “I didn’t know how lonely I’d been until the loneliness stopped,” one of them notes.

Fortunately, Hoban is the most unconventional of fictioneers (one paper called him “the strangest novelist in Britain”), and thus while Turtle Diary contains the dramatic mainstays of love and death, they are not necessarily in the places you expect. What would seem to be the central event doesn’t neatly track as the Moment It All Changed. Though the book is seamlessly readable, the two-voiced structure renders the narrative unstable, its rhythm unfamiliar. William contrasts his and Neaera’s uncomfortable, confusing meeting to the charming way “a film with Peter Ustinov and Maggie Smith” would handle it. “Real life is all the details they leave out,” he thinks. Is the story they find themselves in a proper one, of momentous happenings, of growth and change? Or will they be left behind with their lives running along the same, parallel tracks, the main narrative having been somewhere else all along?

Turtle Diary is not Hoban’s best-known book, though it was adapted into a well-received 1985 film (Harold Pinter wrote the script; Glenda Jackson and Ben Kingsley played the leads). Riddley Walker (1980) is generally considered his masterpiece, a ferociously imagined fiction in which he mints his own language (along the lines of A Clockwork Orange) in a new and brutal iron age; David Mitchell cites it as the chief linguistic inspiration for the central chapter of Cloud Atlas. But more popular by far are the Hoban books it’s likely you’ve already read, or have had read to you: the Frances series, in which the most charismatic of badgers sees ominous shapes as she struggles to sleep (Bedtime for Frances), adjusts to a sibling (A Baby Sister for Frances), has an elaborate picnic (Best Friends for Frances), and broadens her palate (Bread and Jam for Frances).

Hoban was born in 1925 near Philadelphia, went to art school, was awarded a Bronze Star in World War II, and worked as a magazine illustrator and in advertising before finding success as a children’s author. He moved to London with his family in 1969 and got divorced in 1975. (His first wife, Lillian, illustrated all but one of the Frances stories.) By the time Turtle Diary appeared, he had published 37 books for children and two novels for adults.

Surely one reason William and Neaera ring so true is that Hoban sheared off parts of his identity for use as defining aspects. The former is divorced (as Hoban would soon be), living a cramped boardinghouse existence in which clogged drains fill him with rage and magnify the loss of his former life. (Like Hoban, William once worked in advertising.) And Neaera’s popularity as the creator of anthropomorphized critters—Gillian Vole, Delia Swallow—makes her even more cynical about kiddie lit, to the point where she agrees to write a book on the “tragic heritage” of the genre: “possibly the biggest tragedy in children’s literature is that people won’t stop writing it.”

“People write books for children and other people write about the books written for children but I don’t think it’s for the children at all. I think that all the people who worry so much about the children are really worrying about themselves, about keeping their world together and getting the children to help them do it, getting the children to agree that it is indeed a world. Each new generation of children has to be told: ‘This is a world, this is what one does, one lives like this.’ Maybe our constant fear is that a generation of children will come along and say: ‘This is not a world, this is nothing, there’s no way to live at all.’ ”

Such eloquent nihilism makes you rethink the climax of Bedtime for Frances (1960) as a description of coerced consensus, with nothing but violent insanity at the core.

” ’Everybody has a job,’ said Father.

’I have to go to my office every morning at nine o’clock. That is my job. You have to go to sleep so you can be wide awake for school tomorrow. That is your job.’

Frances said, ‘I know, but …’

Father said, ‘I have not finished. If the wind does not blow the curtains, he will be out of a job. If I do not go to the office I will be out of a job. And if you do not go to sleep, do you know what will happen to you?’

’I will be out of a job?’ said Frances.

’No,’ said Father.

’I will get a spanking?’ said Frances.

’Right!’ said Father.”

Hoban’s prose is elegant even at its most brooding, loaded with enough precision-cut lines to fuel your Twitter feed for a month. Yet the chapters also convey the aleatory rhythms and the frequent utter murk of day-to-day living—the details that ground the fantasy in reality. Entries often start with a small observation (“What a weird thing smoking is and I can’t stop it.” “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone pick up a box of matches without shaking it”) that opens up into a worldview. Like the rest of us—like people in real life—they see movies (King Kong, The Swimmer) and read books and reflect on them (separately, of course).

In one offhand bravura passage, William walks over a manhole cover and sees that it’s marked K257. It’s as though the simple fact of his noticing renders the mundane cluster into part of a cryptic code. Later he looks up the Mozart work with the same designation, which turns out to be the Credo Mass in C: “Credo. I believe.” Hoban gets to the lofty by studying what’s right underfoot.

Believe in what? Early in the novel, Mrs. Inchcliff, William’s landlady, thinks aloud about her ex-boyfriend. William notes: “There must be a lot of people in the world being wondered about by people who don’t see them anymore.” If you—solitary, gloomy, cynical you—are thinking of others, isn’t it entirely possible that someone is thinking about you? The sublime keeps cracking through the despair. What is magical about Hoban’s book is simply the possibility of connection: that someone else’s inner thoughts are moving at the same approximate pace and toward the same direction as yours, and that this silent kinship is revealed.

Which makes you wonder: Why is it Turtle Diary, singular, and not Diaries? Both William and Neaera are the writers, but neither of them can be the reader of the whole; the accounts remain quite separate. Could it be that, searching for connection, they have dreamt you, the reader, up? “Between now and then were all kinds of minutes, all of them good,” Neaera writes near the end. “Who knew what might happen at the typewriter?” Even at their lowest points, William and Neaera have kept writing, getting down the texture of their fears. And in writing, they have conjured you, like Shackleton’s third man, so that you can bring to their loneliness your own, and let it stop along with theirs.

—

Turtle Diary by Russell Hoban. New York Review Books.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.