Among the conventions of the author bio, age disclosure has a particular function. Often it signals a debut’s trump note. “Zadie Smith,” a flyleaf of White Teeth informed readers, “was born in North London in 1975.” Jesus, sighed her contemporaries, who in 2000 were still finishing degrees or scrambling for desk jobs. A reader, growing aware of its intended effect, might notice that few authors older than 30 bother with the year drop, and begin to hear double snaps in its wake. X was born in 1978, but Y was (b. 1983), bitches.

Scanning the bio attached to what purpose did i serve in your life, the first book from online lit’s enfant terrible Marie Calloway, I didn’t hear snaps but the voice of Judy Garland. During some mid-duet patter on an episode of her early 1960s variety show, Garland stopped Jack Jones after he mentioned being born in 1938: “Nobody was born in 1938,” Garland said. Of course her dismay is funnier, and sadder—that was young once—50 years later. But seriously, nobody was born in 1990.

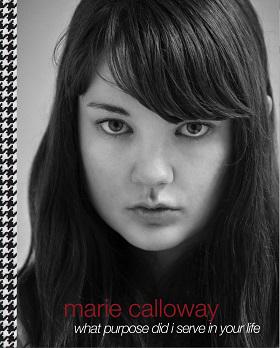

In her debut—a collection of starkly observed, first-person sexual odysseys (some originally published on sites like Thought Catalog and Muumuu House) interspersed with collages of low-res photos and chat transcripts—Calloway’s age forms the self-conscious center of a desperately self-conscious world. The narrator, whom I’ll call Marie (Marie Calloway is a pseudonym, though the author draws heavily from her own experience; close-ups of her face fill the book’s front and back cover, close-ups of other parts of her body are found between them), rarely has a thought unconnected to her sense of a very young self. And rarely is she observed without her age—her youth and beauty—being observed first. Very little guards the border between Marie the subject and Marie the object, and this porousness is the source of a confusion particular both to young women and, perhaps, to this moment.

The pieces are ordered, roughly, to follow Marie from age 18, in 2008, to 22. Often in her interactions with older men—the only kind of man, or person, for that matter, Marie encounters in these stories—she drops her age to discover or refresh its effect. Some of the men are older writers, some are older photographers; some are older johns. In one of the better stories, “Jeremy Lin,” the title character—whose name provides a celebrity membrane for the elsewhere named and pictured author Tao Lin—places half a tablet of MDMA on Marie’s tongue, then looks at her and sighs: “I can’t believe I’m 28.”

That’s the book’s central dynamic, powered always by the narrator’s age: Men respond to Marie. This is both what happens in these stories and what she tells us herself. Often the stories begin with an appointment to meet, and go on to describe a real-world encounter produced by the kind of correspondence Calloway excerpts elsewhere, in which an intricate dance of staccato chat and selfies lead to plane tickets and a more carnal if no less blighted attempt at connection.

In “Adrien Brody,” the story that earned Calloway a profile in the New York Observer and the wrath of the commentariat—along with a few key admirers—Marie emails a 40-year-old cultural theorist to compliment his thoughts on pornography. To his delayed, cordial response she replies with clipped entreaties, like telegrams sent from inside the cloud: “if you want please read my writing zzz…tao lin liked both stories zzz.” “plz add me on fb if you want.” A quick email exchange follows, 10 days pass, and then, Marie tells us, she sends Adrien this:

“hello

I will go to Brooklyn may 26 - june 1

I would love to sleep w/ you

probably you’re not into that sort of thing but thought I would say anyway zz via nothing to lose

goodluck in your life zzz”

As happens throughout the book, Marie explains her motivation in terms that manage to feel simultaneously disarming and disingenuous: “I wanted to keep his attention, so I emailed him again, this time a gallery of photos a friend had taken of me in thigh high socks. I was also curious to see how someone who seemed so dignified and cerebral would respond to a young girl sending sexy photos of herself to him over the Internet.”

The outcome of Marie’s gambit will not surprise you, but the quality of the ambivalence and automatonic detail with which she documents it might. We all know this story, as those who dismiss Calloway as a tiresome or even dangerous kind of disclosure artist point out. What feels unknown enough to be shocking when it surfaces, as it does with some consistency here, is access to the enveloping perspective of an ordinary young woman seeking affirmation, connection, comfort, and other, darker unknowns through sexual contact. If what she describes is the same old anomie, Calloway joins a new chapter in the literature of disaffection. Here self-consciousness, far from a new literary toy, has flattened into landscape, an airless plane where stunted characters pass the occasional pebble back and forth like a cold potato.

***

Melissa Panarello, the Sicilian author who under the pen name Melissa P. published 100 Strokes of the Brush Before Bed at age 18, in 2003, wrote of her sexual extremities in comparatively florid, fairy tale tones. Not for Calloway are spades thrust into “rich, luxuriant soil.” The image of Marie and Adrien Brody discussing Gramsci while doing it, however, is equally laughable. (“I couldn’t pass up the chance to sleep with my intellectual idol,” Marie writes after learning of Adrien Brody’s girlfriend, one of many painfully ingenuous declaratives that stand in place of metaphor, abstraction, and psychological insight.) She adopts in these dialogue-heavy scenes a style of relentless, somewhat remedial observation, like an inverted Lillian Ross reporting with alien fascination on her own feelings and her companion’s limited array of airs, gestures, and expressions. Even Marie’s pleasure seems pleasureless, passive, occurring for the purpose of data collection and dissemination. Compare her description of sex with her first trick—“He lay there and had an erection while I moved”—with that of her more profound, much anticipated assignation, with Adrien Brody: “He penetrated me and I was happy. I felt a strong sexual connection with him.”

This style, with its suggestion of mournful detachment—critic Christian Lorentzen coined the term “Asperger’s realism” to describe the work of Tao Lin—reaches its fullest expression in “Jeremy Lin.” For two such stolid characters, Marie and her mentor do a lot of feeling, first in emails, then in person, then in emails again. “I feel like you know what you’re doing and when I read other people’s advice it makes me feel like I want to help you feel like you don’t need their advice,” Lin writes to Marie in the wake of publishing “Adrien Brody” on his website. Together they feel and they feel like, such that the phrase begins to suggest, amid a profusion of screens and floating personae, a kind of mutual assurance: I feel.

Marie tests Lin, as is her habit, annoying him with her need to be desired as well as championed. “I feel like I felt how you felt when you were lying in the bed not wanting to leave,” he writes to her, after she ends a druggy party lying on Lin’s bed, not wanting to leave. Lin is attempting to communicate empathy, but the abstraction-free style, whereby nothing is taken for granted, suggests a language, after centuries of wanton proliferation, reset to its basic verbs, pronouns, and prepositions. Like couples rebuilding a decimated relationship, Calloway’s characters seem trapped in a specialized therapy session, an endless series of Imago exercises. I feel this when you say that; I hear what you’re saying and it makes me feel this. Most often those feelings are: awkward, embarrassed, worried, lonely, confused, humiliated.

Courtesy of New York Tyrant.

A similar dynamic begins to define the relationship between reader and author. Calloway addresses the reader privately, occasionally expressing concerns about her “career,” a concept indistinguishable from her story, her arc, her sprouted mythology. Of her mentor Marie tells us that she “would probably always feel stifled and overshadowed unless I were to somehow totally disavowal [sic] Jeremy Lin from my life and career, and accept all of the difficulty and pain that would bring. I wondered if I would ever be able to reconcile my ambition to be a serious writer with my desire to be loved.”

Calloway might have worried about awkwardness as much as her character does. Transitions, behavioral logic, and attempts at self-analysis creak or have a studied glibness. (“I did block him,” Calloway writes of one Internet creeper, “but then I got bored and started talking to him. Then I realized I want more pictures of me, so I said he could take mine.”) Marie’s voice sometimes veers from zombie reporter to second-year grad student. “Sex work experience three” opens with a diaristic salvo:

“I need money for BareMinerals foundation and MAC lipstick and soy lattes and pizza. If I earn money I will no longer be a financial burden on my parents; I will be productive and accomplish something. I will be a commodity, and I will be in demand and valuable. I am so beautiful and young that men will pay three hundred dollars to have sex with me; sex work will reify my youth and beauty. I have no friends and nothing to do except school and this will give me something to do and a way to study other people besides through the Internet. I’ll find out for myself what sex work means, and what kind of men pay for sex and why they do it.”

Writing about the HBO show Girls for the New York Review of Books, J. Hoberman suggested that its creator, Lena Dunham, has “tapped into a vein of tragicomic sexual naturalism in which, as in the novels of Czech writers Milan Kundera and Ivan Klima, social constraint (here economic) makes sex, however messy, the lone arena of freedom.” Though it’s tempting to draw Calloway into this same arena—where blood and other fluids are spilled in search of a connection strong enough to obliterate its parties, their worries, their disparities, their fakery, their endless, obscuring refractions—the Dunham connection feels more complicated. The photos, the threesomes, the drugs, the men eager to tout and publish Calloway ASAP, all remind me of Hannah Horvath’s e-book deal with the editor of a pop-up press played, in Season 2 of Girls, by director John Cameron Mitchell. Where’s the sexual failure, he chastises his protégé when she turns in a draft focused on her female friendships. “Where’s the pudgy face slick with semen and sadness?”

More than once I have heard expressed by other women—particularly woman writers—the wish that Calloway and her book simply didn’t exist, that we might all just ignore it. It’s a weary wish, not a malicious one: It would just be easier, they sigh, and maybe better that way. I confess that being asked to write about this book inspired in me a similar wish—that the email had not been sent, that I would not have to decide—and mine was as useless. The experience of reading what purpose did i serve in your life, which rides the line between performed and genuine vapidity and malign naiveté so closely that the distinction between them blurs, is by turns dull, titillating, appalling, riveting, and as head-spinning, in Hoberman’s phrase, as “a hall of mirrors in which Girl Power and female powerlessness are endlessly reflected.” It is not, in other words, easy to turn away from. Easier, perhaps, to catch a shattered glance of oneself.

What Calloway depicts most persuasively is a young woman’s intrigue with herself—her transient powers and her highly exploitable weaknesses. Though she makes sexual discoveries, somehow freedom has little to do with it. Rather than sexual ecstasy, Marie reaches for her camera; pornographic shadows flicker around every coupling. In a book describing at least a dozen sexual encounters, Marie’s orgasm count never budges. When it appears, the word “love” has a random, retrospective quality: Marie might claim, two stories later, to love the partner from two stories back, but we can only take her word for it. Sex may be one arena of freedom, these stories imply, but the page is where the bloodied seek a rematch.

Finally, the book’s emphasis on scene suggests a failure of story: With the size and feel of a coloring book, what purpose did i serve in your life appears as an outline of sorts, something preliminary. An exercise in self-portraiture as modern self-mythology, it’s a book I can imagine appreciating best at 19, while taking cover in some furtive bedroom from the betrayals of young womanhood. But I’m not 19, and neither, anymore, is Marie Calloway. That was young once.

—

what purpose did i serve in your life by Marie Calloway. New York Tyrant.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.