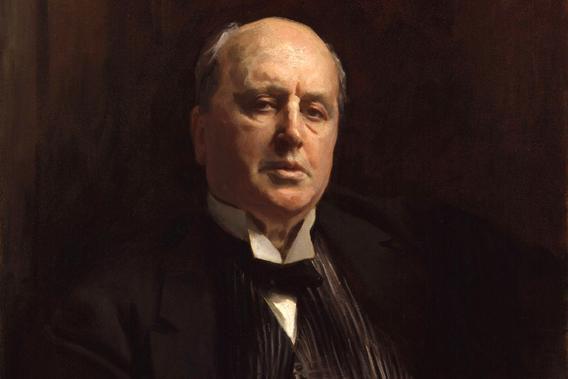

This article is excerpted from the introduction to Melville House’s new edition of Henry James’ novel The Reverberator.

Pretty pre-socialite May Marcy McClellan’s father had run for president against Abraham Lincoln in 1864 and later became governor of New Jersey. Her brother would, in 1904, become the mayor of New York City and beat William Randolph Hearst for his second term; he had “drifted” into politics, as his Times obituary hilariously put it, upon becoming close with Tammany Hall figures while a politics reporter. Which is to say, she was fancy.

On Nov. 14, 1886—shortly after her father died and shortly before her mother settled on Fifth Avenue across the street from the Astors—McClellan published an account of her recent time in Italy in the New York World. She begins with some lush description and immediately scores a wild gaffe at the end of the first paragraph: “The picturesque Hotel Excelsior, situated on a hill some little distance from the town, was formerly a villa belonging to the patrician family of Morosini, of Venice, but a few years ago they were obliged for pecuniary reason to sell it.”

She relays the current “Anglomania”: “The Romans and Neapolitans have it badly; it made me feel quite at home to see the preternaturally grave expression, the lurching walk and excessively British garments of these Latin dudes.” She then goes on about a “Princess Zucchini”—it really is like a parody!—and how the beauty of these people is their simplicity: the olive eyes, the early marriages, the handsome men …

This hilarious, probably racist but also really quite charming column, running on Page 10 as it did, still resulted in much astonished clutching of those European pearls. Henry James saw McClellan in Florence just a few months later and subsequently absolutely trashed her in private letters to friends.

The column and the outcry had such an impact that, one year and three days later, James laid out the tale for himself—in quite a dishy fashion, as was the custom for his notebooks—along with the ways in which he would disguise and alter it for a novel:

“Last winter, in Florence, I was struck with the queer incident of Miss McC.’s writing to the New York World that inconceivable letter about the Venetian society whose hospitality she had just been enjoying—and the strange typicality of the whole thing. She acted in perfect good faith and was amazed, and felt injured and persecuted, when an outcry and an indignation were the result … I shouldn’t have thought of the incident if in its main outline it hadn’t occurred: one can’t say a pretty and ‘nice’ American girl wouldn’t do such a thing, simply because there was a Miss McC. who did it … ”

Just two weeks from then James was pitching this story to an editor, and The Reverberator, the result of these notes, began serialization in Macmillan’s three months later, in February 1888. It overlapped with the serial publication of The Aspern Papers in the Atlantic. (This was when Henry James was working on a Woody Allen schedule.)

The story that sprang from the International McClellan Incident is of Francie Dosson, a pretty and rich 25-year-old American girl. She and her unpretty, conniving sister and simple father come from Boston to Paris. At sea they meet a reporter named George Flack, who then tours them through town. Flack falls for Francie but has introduced her to a trendy painter, who is painting frightening “Impressionist” portraits. (Sidebar! 1888 was already 16 official years into Impressionism; that year Gauguin was painting alongside Van Gogh, and Monet began his endless haystacks.) This painter’s best friend, of an American family (from “Carolina”) that has married ridiculously well into France and become Frencher-than-thou, falls for Francie as well. In the face of rivalry Flack decides he wants more than just Francie: He’s also after some hot copy for his American paper, The Reverberator.

A third of the way through the book, Mr. Flack delivers a chilling and visionary speech to Francie that he expanded for the (wordier, less punchy) New York edition of 1908, to give this mildly terrifying manifesto:

“The society-news of every quarter of the globe, furnished by the prominent members themselves—oh they can be fixed, you’ll see!—from day to day and from hour to hour and served up hot at every breakfast-table in the United States: that’s what the American people want and that’s what the American people are going to have … That’s about played out, anyway, the idea of sticking up a sign of ‘private’ and ‘hands off’ and ‘no thoroughfare’ and thinking you can keep the place to yourself.”

Well, yow. So Henry James Nostradamus’d People magazine and TMZ and actually much of the way we live now.

***

Newspapers were (and are?) a great business, but they were always desperate to get a leg up. When the New York Times began in 1851, already hundreds upon hundreds of New York newspapers had risen and died—and William Randolph Hearst only bought his first New York newspaper in 1895. In the battle to stay ahead, publications competed—for example, to see who could obtain the fastest boat, so as to get the news quickest from the ships arriving from Europe and scurry it back to the typesetter. In this competition, New York papers were engineering what was seen as a war on society.

“Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops,’ ” wrote Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in the Harvard Law Review in 1890, in a rather overwrought attack on the press in an age when “personal gossip attains the dignity of print.” This is what Henry James saw as the new “devouring publicity of life, the extinction of all sense between public and private.”

While America was beginning this slide into celebrity tabloidism, and the first New York Social Register—a European import done up in a truly American style—came into being in 1886, it was also the case that in both America and England compulsory education had begun to spread literacy further among the nonrich. So staunch advocacy journalism about the “lower classes” was being put forward at the same time that these growing audiences of women and nonrich people were discovered to be opportunities for new journalism products. Tit-Bits, a silly blog of a thing, was founded in 1881; the idea for a publication filled with small news and notes and humor for ladies came about, recounts Margaret Beetham in A Magazine of Her Own? (1996), because a bigwig newspaper editor read items from the real, big-boy paper to his wife, and she just enjoyed it ever so much.

This all sounds like a great deal of amazing fun, but when Hearst burst onto the market in 1895 with his New York Journal, the papers promptly became louder, bolder, more crime-obsessed, more graphic, and of course more tabloid—tabloid in a manner nearly identical to the one we know today. Unfortunately, at the same time, the papers also became far less true. What James and others feared certainly came to pass. For better—the media now, for instance, does not necessarily solely serve to protect the interests of the rich—and for worse, but mostly for capitalism, we absolutely discarded many of the old notions of privacy.

***

Reviews of The Reverberator were all over the map. The New York Times gave it a pretty solid and dismissive pan. Robert Bridges in Time came a bit later, noted these bad reviews, and suggested a reason: “Perhaps the severe criticisms of the press were not a little prompted by the prickings of the editorial conscience, which in its rare moments of introspection discovers how hard it is for the man of best intentions to publish a wide-awake newspaper and not violate some of the conventions by ‘invading the sanctities of the home.’ ”

As for the rest of us, the young girls in search of high society and the greedy journalists and the terrible rich people who own newspapers, not much has really changed. Certainly in New York City, it all seems to come around again and again. On the front page of the same New York World that contained poor May McClellan’s charming Italian diary, there ran a story with the hysterical headline “ARE THE RICH GROWING POORER?” “There is great poverty and much unseen suffering in New York, beyond doubt,” it noted. “But it is a city imperial in wealth and luxury.” The story went on, about the art, the jewels, the newly rich, the “waters studded with pleasure yachts, floating palaces.” In the end, the answer to the headline, as it is to almost every question in a headline, turned out to be “no.” But wouldn’t it fit just perfectly on the front of the Times’ Style section today?

—

The Reverberator by Henry James. Melville House.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.