“I was supposed to be having the time of my life,” Sylvia Plath’s young protagonist sighs in the 1963 classic The Bell Jar. Sulking, acerbic Esther Greenwood—Holden Caulfield in a shantung sheath—is in Manhattan, supposedly “having a real whirl,” but is actually spending most of her time obsessing over executions and stuffing herself with expensive condiments. “I just bumped from my hotel to work and to parties and from parties to my hotel and back to work like a numb trolleybus,” she admits. She manages to make New York and all of its youthful splendors sound like a Bataan death march for striving debutantes, which, while not unrealistic, is hardly the Manhattan dream.

That’s probably why Elizabeth Winder’s Pain, Parties, Work, the most recent addition to the ever-expanding Plath biographical oeuvre, feels so unlikely. Much of the book, about Plath’s month in New York City in 1953, is downright cheery. Then a 20-year-old student at Smith College, she won a spot as a guest editor for Mademoiselle’s annual college issue and would live with 19 other young “guest editors” spending a month in New York filled with parties, fashion shows, dates, ballets, cocktails, and caviar, mostly paid for by the magazine. When she arrived on May 31, she had a new wardrobe, a perfect pageboy haircut, and plenty of red lipstick.

She was also 58 days away from her first suicide attempt and 10 years away from publishing The Bell Jar, the roman à clef that chronicled that month in New York and her ensuing breakdown. (She killed herself just a few months after the book was published.) How did this golden girl go from the pinnacle of her budding career to sitting in a crawl space, swallowing a bottle of Nembutal?

Plath was, as Winder points out, part of a growing tide of young, single women moving to New York, which was becoming “a safe haven for women who were more interested in becoming fully formed adults than wives and mothers.” Her base was on 63rd and Lexington Avenue at the Barbizon, the famed all-women’s hotel and protector of female virtue. (Other residents of note over the years included Grace Kelly, Joan Crawford, Liza Minnelli, Eudora Welty, and Joan Didion, who did her own stint as a Mademoiselle guest editor.) The young editors each had a small, un-air conditioned room at the hotel, from which they would walk to the Mademoiselle offices on 79th Street.

As the guest managing editor, Plath’s work at the magazine was particularly demanding. Soon she was “spending hours chained to a makeshift desk” under the watchful gaze of editor Cyrilly Abels, who realized just how talented the young writer was. But Plath didn’t just want to work. Like most 20-year-olds, she was there to stay up late with the other editors and wear strapless silver lamé dresses and drink daiquiris and, of course, date. Before she made it to New York, Plath wrote in her diary, “My consuming interest in men and their lives is often misconstrued as a desire to seduce them, or as an invitation to intimacy. Yet, God, I want to talk about everybody.” In New York, she hoped to meet an endless array of new characters and headed out with everyone from preppy Ivy Leaguers to South American diplomats (although she was ultimately disappointed).

When delving into Plath’s short life, biographers have more or less focused on her older years, particularly her turbulent relationship with future British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes. Winder sees her book as “an attempt to undo the cliché of Plath as the demon-plagued artist.” (Andrew Wilson’s recent Plath biography, Mad Girl’s Love Song, also refocuses on the pre-Hughes years.) She relies heavily on interviews with the other 1953 Mademoiselle guest editors to paint a rather different image of Plath from the one most readers are familiar with today. On these pages, we get a portrait of the artist as a typical young woman in 1950s America. “Sylvia seemed to me like a girl who was eager to please,” says fellow guest editor Gloria Kirshner. “She was anxious to do right—the epitome of the good girl.” Another describes her as “slightly unapproachable, but not awkward or shy or rude. She was very pleasant and courteous. One felt like you couldn’t tell her a dirty joke.” And Carol Levarn, the young woman whom Plath twisted into The Bell Jar’s wild Southern belle Doreen, distills what most of the women seem to be thinking: “I never could have imagined the life she had ahead of her. She seemed just like me.”

In her seminal 1994 work on Plath and Ted Hughes, The Silent Woman, Janet Malcolm writes, “The history of her life … is a signature story of the fearful, double-faced fifties. Plath embodies in a vivid, almost emblematic way the schizoid character of the period. She is the divided self par excellence.” It is Plath’s ability to express these divisions—the good American girl and the unhinged poetess, the wife and mother and the mentally ill cynic—that has made her an object of fascination for the past half-century. Plath was not unaware of her central position in the zeitgeist. In 1957, she wrote in her journal about The Bell Jar’s Esther Greenwood, “Make her a statement of the generation. Which is you.”

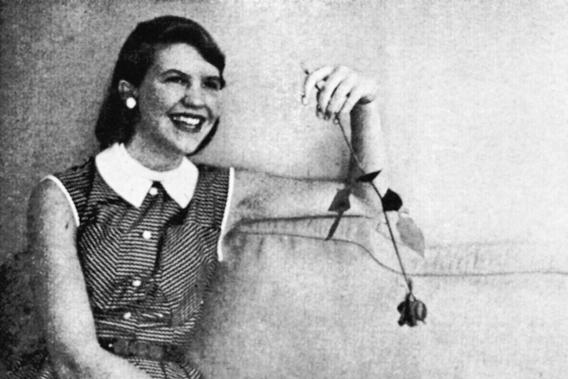

Photo by Reed Pedlow

Through her fictional alter ego, Plath was able to combine her light and dark selves into one uncomfortable, ungrateful, neurotic, beautiful, successful, damaged girl. It was the real Plath’s inability to construct a cohesive self out of these competing forces that, when combined with the crucible that is New York City, pushed her toward a breakdown. According to Winder, her deepening anxiety resulted from “the precarious nature of her own happiness, the instability of character, persona, identity, even affection. The instability of identity—how we are seen only one dimension at a time.”

Unfortunately for Plath, the habit of pigeonholing is a difficult one for humanity to shake. Winder, at times, pushes a touch too hard to portray a Sylvia who is missing the dark, bitter streak that always animated Plath’s journals and early writings. She insists perhaps too readily that Plath, who was fascinated by aesthetic beauty, “would have been a perfect fashion editor.” Perhaps, but one hardly longs for a world where instead of Ariel, Plath gave us 14 column inches on periwinkle. It’s doubtful the fiercely ambitious Plath would have wanted that, either.

When describing Plath’s successes, most writers cannot help but pan up, however briefly, to show the sword of Damocles dangling above her bleached blond hair. She was, in addition to her many gifts, terribly sick, suffering from depression and probably bipolar disorder in a time woefully unequipped to treat either. Since we know the ending of the story, an aura of melancholy and angst permeate, making the sad stories even sadder and lending the happy ones a bittersweet tinge. But reading The Bell Jar, one is reminded of Plath’s ironic wit and pitch-perfect appreciation for the absurd. Winder resuscitates a young woman who, while sick, is electrically alive to her first real adventure, running through Manhattan, jumping into cabs with strange men, trawling the racks at Bloomingdale’s and experimenting with cocktails. This girl is not quite as funny or fearless as Esther Greenwood, who was the more polished work of a slightly older woman, but is captivating in her own right as she struggles with her choices, anxiety, and hope for the future.

Winder wisely doesn’t end her story with Plath’s suicide attempt but tells us how, just 10 months after she left Manhattan and Mademoiselle psychically wounded in ways that would only too soon become clear, she flew back to the city. She saw friends, had lunch with her former editor, ran around the Village, and rode the Staten Island ferry. Winder’s portrait is of a resilient young woman who battled mental illness and rampant sexism in a society mired years behind her progressive vision of herself and life’s possibilities. She makes a compelling argument that in New York, while she paid a terrible cost, Plath moved closer to finding the voice that would define her writing.

It is not the classic New York success tale: There is no great romance or passionate lovemaking, there’s no dream job at the end of a grueling ordeal, and rather than the de rigueur cosmopolitan makeover, Plath ended her stay in Manhattan by throwing her clothes off the roof of her hotel, returning home in a borrowed peasant blouse. But she did learn a key New York lesson: that if you push as hard as you can, you will, for better or worse, learn things about yourself you would never have otherwise known. The proper young lady, so eager to please, who first appeared on the Upper East Side, was slowly being replaced by the powerful writer she would become. What hadn’t killed her made Plath stronger. Until, of course, it killed her.

—

Pain, Parties, Work: Sylvia Plath in New York, Summer 1953 by Elizabeth Winder. Harper.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.