The term egghead has mostly been retired to the Hall of Lost Insults, hung up alongside Poindexter and gomer in the “Making Fun of Nerds” section. But being accused of being an “egghead” in the 1950s wasn’t the same as being called a “geek” today. The epithet connoted high-minded idealism, self-indulgent impracticality, and a vulnerable breakability in the face of real-world conditions. Wrote novelist Louis Bromfield in a 1952 issue of the libertarian journal Freeman:

“Egghead: A person of spurious intellectual pretensions. … Over-emotional and feminine in reactions to any problem. … Emotionally confused in thought. … a self-conscious prig, so given to examining all sides of a question that he becomes thoroughly addled while remaining always in the same spot.”

Adlai Stevenson, the Illinois governor and 1952 and 1956 Democratic presidential nominee was probably the most famous egghead of his time. A Unitarian (of course!), Stevenson would write and rewrite (and rewrite) his speeches. He bought half-hour blocks of television airtime, thinking that he’d use it to explain complicated issues to the public. In competition with the avuncular Eisenhower, a plain-spoken war hero, Stevenson lost—twice. (Stevenson had a sense of humor about his image. He once replied, when asked about being an intellectual in politics: “Via ovicapitum dura est”—“The way of the egghead is hard.”)

As Aaron Lecklider’s surprising history Inventing the Egghead shows, the figure of the unworldly and fragile genius showed up across postwar popular culture, in comic pop songs, science fiction, television, and the theater. Lecklider shows how the suddenly omnipresent and mockable egghead was a creature of its time, born of postwar anxieties over Communism, gender roles, and race. He argues that the national sport of making fun of eggheads had far-reaching consequences. To stereotype people interested in ideas as elite, “soft,” white, and male was to restrain the definition of intelligence—to “limit those for whom intelligence was culturally available.”

In order to make his argument, Lecklider has to show that before the Cold War, a broad range of Americans admired the qualities later associated with eggheadery. In his influential 1963 work on the topic, historian Richard Hofstadter argued that anti-eggheadism—or, to strip the term of its slang, anti-intellectualism—had been pervasive in American life all along. Lecklider, on the other hand, thinks that instead of being a particularly virulent manifestation of an ongoing strain of American thought, the invention of the hated egghead represented an abrupt departure from previous popular attitudes toward intelligence.

Ranging across bits and pieces of popular culture from the first half of the 20th century, Lecklider presents us with a series of cases meant to prove that before the Cold War, everyday people both respected intellectual activity and claimed it for their own. In this “organic intellectual tradition,” women, working-class people, and minorities redefined “intelligence” as a quality that the marginalized could use to gain power. Moreover, “brainpower” was democratic—transmittable through the ad-hoc and cheap educational vector of popular culture.

Coney Island was a magnificent carnival in the early 20th century, stuffed full of games, roller coasters, and freak shows. Yet in 1909 it also contained the Luna Park Institute of Science, where employees wore nametags identifying themselves as “professors,” and people learned about wireless radio, the engineering of the Panama Canal, and the new technology of the baby incubator. Meanwhile, the Chautauqua lecture circuit, a staple of late 19th and early 20th century middle-class culture, promised brief, entertaining introductions to new ideas, given by experts. The experience of going to a Chautauqua in person was supposed to be fun, empowering, and exciting, all in one package. People traveled miles to attend lectures on their summer vacations. Workers’ education movements in the 1920s brought industrial laborers to college campuses for brief, intense “schools.” At the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers, held during the 1920s, students took courses in music appreciation, economics, science, and English.

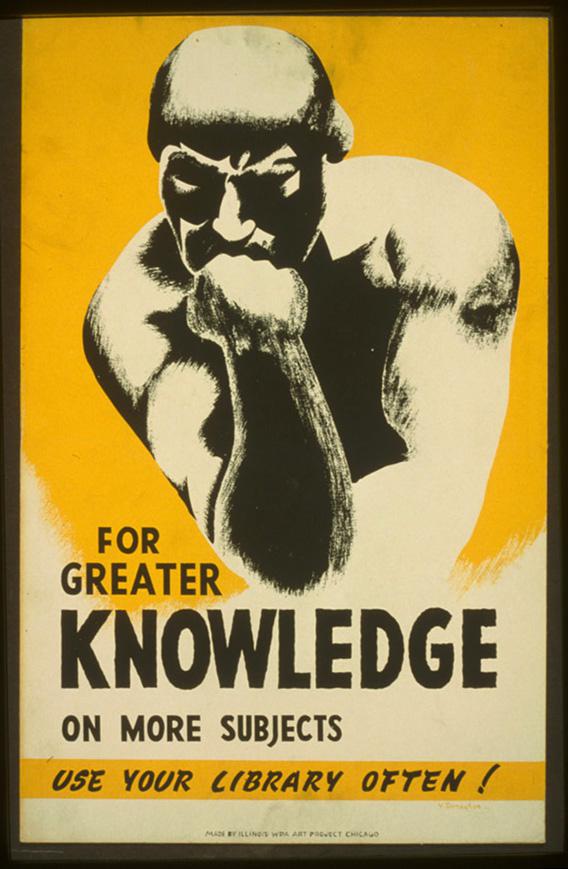

Placed in this context, WPA-produced posters promoting libraries and reading during the Depression make more sense. These striking images now look like quaint examples of a bygone culture that put more stock in the “right” things. (They are oft-circulated in the parts of the Internet that like libraries, history, and books.) Lecklider shows how the posters promoted reading for industrial workers and African-Americans during a time when those groups were increasingly economically threatened. The posters associated the work of the body with the work of the mind.

How did we, as a culture, bridge the gap between a world full of “proletarian cognoscenti” and the feminized, privileged “egghead”? Lecklider points to the media coverage of the Manhattan Project, and, in particular, the postwar revelation of the secret planned community of scientific workers in Oak Ridge, Tenn., to argue that this was a watershed event in the intellectuals’ retreat behind closed doors. After Hiroshima, that feeling of separation between everyday people and the intellectuals employed to think up the bomb got bigger, amplified by the terrifying consequences of all that brainwork. The press exacerbated the situation by pointing up the contrast between the Oak Ridge scientists and the rural Tennesseeans who lived nearby.

Courtesy of Brian Halley

Lecklider’s story largely ends in the 1960s, leaving me to wonder how today’s popular culture might compare with his recovered pre-war “organic intellectual tradition.” It’s certainly not difficult to find the kind of widely available educational popular culture that Lecklider looks back upon with some nostalgia. Are MOOCs the new Chautauquas? What about a resource like Open Culture, a Web repository of freely available textbooks, lectures, movies, and language lessons? People really like the History Channel and the Discovery Channel. Is their brand of “educational fun,” with its flashy packaging and dubious content, the latter-day version of the Luna Park Institute of Science?

The growth of an increasingly powerful and specialized military-industrial complex built on eggheady science might be Lecklider’s most concrete historical explanation for intellectuals’ increasingly precarious position in mainstream culture. In a more speculative connection, he argues that intellectualism fell out of favor because it suited those who held power. If eggheads could be painted as a little bit Communist, maybe a little bit homosexual, that image would scare working-class people away from potentially empowering intellectual pursuits.

For all their wide availability, MOOCs rarely address open-ended, speculative topics. They’re overwhelmingly focused on technical and practical subjects—a few high-profile classes in modern poetry aside. They offer deliverables. A project like Open Culture is a firehose of accumulated resources, offered without a political agenda beyond general enrichment. Its very digital nature means that a certain segment of the population won’t have access to its riches.

As for popular “educational” TV, it’s full of Vikings, Nazis, and baby whisperers.

We still have programs that bring poetry into prisons, or give low-income adults free classes in the humanities. These labor-intensive, tiny, grass-roots programs might come the closest to providing a space for the kind of working-class intellectual empowerment Lecklider calls for in his conclusion.

Finally: Via ovicapitum dura est, but a majority of the electorate picked the notably eggheady Barack Obama—twice. This book shows that respect for intellectuals—especially ones that came from relatively humble roots, like the president—is an American tradition, too.

—

Inventing the Egghead by Aaron Lecklider. University of Pennsylvania Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.