Are losers interesting? Considering the herd of suburban strivers who crowd our fiction shelves, publishers seem to think not. You can almost picture them scribbling “Unlikeable!” on page after page of dark manuscripts, sidestepping tales of self-righteous day care workers with anger issues and depressed men engaged in affairs with their former mothers-in-law in favor of yet another tale of infidelity between sane, productive members of society.

Thank the sweet Lord, then, for Sam Lipsyte, whose twisted tales make sane, productive citizens look like a shadowy curse upon the land. In his new story collection, The Fun Parts, Lipsyte suggests that sanity and productivity are not, in fact, sane, productive responses to a world gone mad. Contempt, alienation, and escape—into fantasy, prophecies, heroin, papaya smoothies—these are the more natural responses to our late capitalist frightmare.

Here and in his earlier books—three novels and another story collection—Lipsyte has cultivated a sensitivity to the ways that economic swings and social uncertainty make desperados of us all. He recognizes the flavors of avoidance that build up around unfounded hopes and poorly charted dreams. Consider Gunderson, the self-proclaimed prophet at the center of “The Real-Ass Jumbo,” a man who seems almost to long for the apocalypse. As Gunderson’s life falls to pieces around him—his pitch for a reality TV show appears doomed and he’s reduced to squatting in his ex-wife’s duplex while she’s away—he retreats into end-times visions and conversations with an imaginary golden guru. And yet this feels less like a descent into madness and more like his only chance at survival. By making willful delusion and other objectively bad choices seem perfectly rational, Lipsyte gets us firmly on the side of his protagonists, whether it’s Gunderson begging his golden guru for answers as his time runs out or Mitch, in “The Wisdom of the Doulas,” brandishing nunchucks at the busy and important parents of a baby named Prague.

Like a cross between Mary Gaitskill and David Foster Wallace, Lipsyte has palpable affection for precocious misfits who, instead of living up to their advantages and talents, slip and fall and never really recover. Again and again, the protagonists of The Fun Parts start out humiliated and slide lower from there, moving gradually from debasement to hopelessness. Readers lucky enough to have met Milo, the sad sack at the center of Lipsyte’s vivid satirical novel The Ask, may recognize that trajectory. But in contrast to self-destruction-as-romance novelists like Charles Bukowski or Chuck Palahniuk, Lipsyte traces his characters’ wildest misperceptions and most repugnant dysfunctional tics without glorifying or condemning them. Take “This Appointment Occurs in the Past,” in which former college friends convene to revisit old wounds and possibly inflict some new ones. Our protagonist, after confessing his love for an old friend’s big ideas, confides, “I wasn’t one of those narcissists who thought I had to understand something for it to be important. Besides, he wasn’t wrong about whatever the hell he meant.”

Distilling this kind of absurd preening—egos aloft on clouds of hot air, bitterness cloaked in self-conscious, choreographed swagger—is one of Lipsyte’s great gifts. Even more remarkably, though, he summons empathy for these petty miscreants and makes you understand them. “We were poseurs,” the protagonist muses, “but why do you think poseurs pose? Because they want to be invited to the dominion of the real, an almost magical zone of unselfed sensation, and they know their very desire for it disqualifies them. Dude just wants to feel.” Psychosocial projections are scattered throughout the story, even in the most mundane details. “The dashboard robot in the Mazda goaded. Beneath its officious tones I sensed confusion, a geopositional wound. Had some caustic robot daddy made it feel directionless?” We learn in passing that our nameless protagonist’s father once “recited a limerick that began ‘There once was a dumb fucking boy/ who was never his daddy’s joy.’ ”

But Lipsyte never seeks refuge in characters who are too knowledgeable or heroically self-aware. In “Nate’s Pain Is Now,” an author of confessional addiction memoirs—Bang the Dope Slowly and its follow-up, I Shoot Horse, Don’t I?—realizes that he’s fallen out of fashion. “The world had worthier victims,” he explains. “Slavers pimped out war orphans in hovels hung with rat-chewed velveteen. Babies starved on the desert floor.” In a hilariously humbled moment, the downtrodden author admits of his father, “It’s true he never hit me. A father need not hit. His coughs, his smirks, are blows. Even a father’s embrace confers a kind of violence. Or so I once pronounced on public radio.” Despite his outsized self-pity, the man increasingly solicits our sympathy. Through absurdities and exaggerations, Lipsyte illustrates how fickle markets and fickle tastes giveth and taketh away in head-spinning succession—everything that is celebrated and embraced is eventually scorned in equal measure (and then graphed in New York magazine.) “You mattered to me once,” a stranger tells the author on the bus. “What happened?” the author asks. “You mattered to me less and less,” she replies, as if her shifting tastes not only require no justification but are somehow the author’s fault. The author’s ego deflates like a balloon animal, and the implication is clear: In these capricious times, no one is immune to such violent shifts in fortune.

Even when his characters border on sociopathic, Lipsyte still evokes our compassion for them. “The Dungeon Master,” one of the collection’s strongest stories, presents a group of boys enduring the whims of their imaginative but tyrannical D&D guide. The dungeon master’s little brother, Marco, is singled out for the most brutal treatment. “Marco is a paladin. He fights for the glory of Christ. Marco has been many paladins since winter break. They are all named Valentine, and the Dungeon Master makes certain they die with the least amount of dignity.” The dungeon master’s mother has apparently fled the scene, but his father “sticks his bushy head in the door, says, ‘Play nice, my beautiful puppies.’ ” Like his father and brother, the dungeon master seems relatively harmless—that is, until he transforms a dying ogre into the ghost of the real-life drowned little sister of one of the players. The boy starts to cry; our young narrator rises to his defense. A brawl breaks out. When it’s over, the narrator crawls to the window. “In the next yard, some kids kick a ball. It looks wonderful.” The bewilderment of childhood, its loneliness and lack of boundaries, the longing that arises from the repeated sensation that you’re in the wrong place with the wrong people—Lipsyte conjures these disparate sensations with one melancholy image.

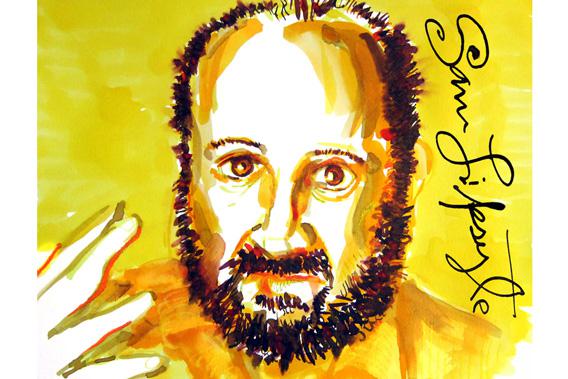

Courtesy of Ceridwen Morris

There is something courageous about Lipsyte’s losers, even in their ignorance, their vanities, and their desperate grabs for attention. And Lipsyte shows us how much we—with our fragile, hungry egos—have in common with a lonely kid, an extremely unskilled doula, or a junkie who is determined to write a children’s book about middleweight boxer Marvin Hagler (“The Worm in Philly”). Maybe that’s why these sad stories impart such a feeling of giddiness: By questioning the real gains of so-called winners and highlighting the subversive advances of so-called losers, Lipsyte frees us from the grip of false gods. His loser-heroes aren’t merely underdogs, they’re nihilistic seers who by understanding their predicament and graphing their own decline stumble on some sliver of salvation. In a last-ditch attempt at existential redemption, they give up on the hungry maw of ego and surrender, at last, to that “sweet caress of absolutely nothing.” If there’s a moral to these stories, it’s this: Whatever trivialities and petty grudges rule us, they melt away in the face of our ultimate fate. We’re all doomed in the end. So why not let go of such vanities and savor whatever trivial joys we can manage?

Some hints of this lesson lie at the heart of “Ode to Oldcorn,” in which a group of shot-putters are laid low by a wunderkind named Bucky Schmidt from a rival school. The world is divided between “those who have met their Bucky Schmidt and those who have their Bucky coming,” the young narrator explains.

“I’ve met my Bucky Schmidt and so I’m never disappointed by the way of things. I don’t want and want. Good money, good times, I’m happy for what I get. You don’t worry so much about it all when you know there is somebody out there who can take everything away like some terrible god.”

Leave it to Lipsyte to make humiliation and defeat sound not just inspiring, but downright transformative. Modern scribes of satire: Meet your Bucky Schmidt.

—

The Fun Parts by Sam Lipsyte. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.