Ten years ago, Mary Szybist’s debut book of poems arrived trailing blurbs from Donald Justice, Jorie Graham, and Robert Hass. She picked up rave reviews and a nomination for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and then, for the next decade, no more books arrived. Incarnadine, which finally closes that bracket, is an oddly quiet and disquieting collection and an unlikely, if welcome, answer for that duration. In Incarnadine, Szybist longs for God and longs to long for God and treats her own longing with occasional scorn. The book is a mix of good manners and postmodern invention. At her most outlandish (a poem in the form of a sentence diagram, for instance), Szybist still sounds relatively conventional. At her most conventional, she’s up to something strange.

Incarnadine is loosely structured around a pun: the author’s first name. Almost one in every four poems is an Annunciation: “Annunciation (from the grass beneath them),” “Annunciation in Nabokov and Starr.” (The latter borrows language from Lolita and the Starr Report; another borrows from George W. Bush and Sen. Robert Byrd.) The sometimes-absent Marys of those poems snare and tangle childhood faith and adult childlessness, and as Szybist equates that childlessness with a lack of purpose, the angel Gabriel starts to look, in his own absence, like an uncomfortable stand-in for a unreliable muse: “what meanings / can I place in you?”

At times, her language feels uninspired, immaterial. There’s something too plain about it, too willing to settle for an ideal that has gotten small—“Already it’s hard to remember / how you used to comb your hair”—and then some repeated note reframes it, and then, a couple pages later, Szybist has made it haunting again: “Days go by when I do nothing but underline the damp edge of myself.” It’s unsettling in part because that motion makes it hard to trust such beauty, even as the beauty pulls. Szybist makes herself unreliable by so apparently trying to tell us the truth. She observes, writing of herself:

“Mary secretly thinks she is pretty and therefore deserves to be loved.

Mary tells herself that if only she could only have a child she could carry around like an extra lung, the emptiness inside her would stop gnawing.”

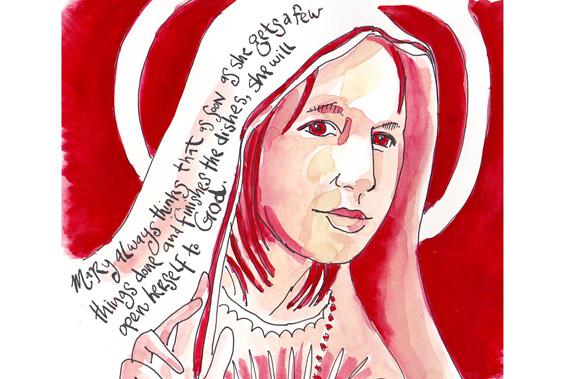

That poem, “Update on Mary,” begins with a declaration that “Mary always thinks that as soon as she gets a few more things done and finishes the dishes, she will open herself to God.” The light comedy of that sentence sets the tone for the rest of the poem, highlighting a world in which God seems not so much absent as incommensurate—un-American, even. Inasmuch as this book does in fact reflect the years in which it didn’t yet exist, the ones in which no new book by Mary Szybist kept arriving, it suggests a time in which life had lost its confident urgency.

As the book moves forward, Szybist persistently tightens the association between revelation and destruction, presenting the other side of an unspoken loss that seems to lurk in the decade Incarnadine emerges from: a loss of faith, urgency, purpose, love, inspiration—some or all or none—whatever made necessary speech possible before. That old confidence lurks in a deliberately haphazard iconography that contrasts with the careful arrangement of symbols in the Catholic paintings Szybist mentions. Religious symbols, such as Mary’s blue garment, or the red of the book’s title (which suggests everything from incarnation to the monthly absence of conception), recur in these poems, but they never resolve.

The annunciations grow increasingly violent. The Leda-esque sense of violation gets more pronounced. Meanwhile, Szybist presents her own fascination with stories of mothers killing their children. And, in “On a Spring Day in Baltimore, the Art Teacher Asks the Class to Draw Flowers,” she learns of an art teacher who sexually assaulted a young student—a teacher, she reveals, who flattered her, when they were both young, by sketching her constantly over the course of a summer. “To be beheld like that,” she explains, “it felt like glittering,” and that odd word “glittering” keeps a particularly American youth in the frame. The loss of her mother feels like losing that, she’ll suggest a little later on. So does (or is it would?) the loss of God.

It’s irony that keeps Szybist’s singing intact. She finds new beauty in estrangement, particularly in inhuman scenes where her imagination can overflow. In one version, the ravishing “Do Not Desire Me, Imagine Me,” she writes, in a row marked “As Corpse,” “Loosened, bare, profusely female / the pulse in my thigh / unthreaded.” Unworldly and ungodly, lines like these pull Szybist beyond the propriety that restricts her and the violence that warns her away.

Courtesy of Joni Kabana

“Knock me or nothing,” she pleads at the outset of another poem, “the things of this world / ring in me, shrill-gorged and shrewish.” It’s an astonishing couplet, Hopkinsesque in its wild grandeur. It’s also an unusual presence here, since Szybist declines, for the most part, to get carried away. Incarnadine’s first line asks permission to honor the troubadours: “Just for this evening, let’s not mock them.”

Characteristically, that poem manages to be both a small domestic scene, deftly rendered and overcrowded with misfit desires, and an image of an artist trying to arrange the world to overwhelm her. The more time I spend with Incarnadine, the more elusive it feels—whatever new insight I come across, digging deeper, I soon realize that Szybist was there first. And yet the book’s original, rich immediacy stays present, much as an array of mockable visions stays present for Szybist’s speaker—stifling and seducing. Midway through “The Troubadours, Etc.,” she offers a stunning account of a time when passenger pigeons covered sun, sky and even sound for days. She concludes, “When they stopped, Audubon observed, / they broke the limbs of stout trees by the weight of their numbers.” And then, skipping a line, she picks up the domestic scene again: “And when we stop we’ll follow—what? / Our hearts?”

—

Incarnadine by Mary Szybist. Graywolf.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter