If you’re like me, you read the unabridged Pride and Prejudice in fifth grade, ate lunch in the library all through high school, and often fixate on the Purpose of Literature. If you’re like me, you’ll understand that a book titled The Story of My Purity (aka what I’ve been calling my teens and early 20s) brought up a few questions.

The Story of My Purity, translated from Italian by Stephen Twilley, is a novel narrated by Piero Rosini, a 33-year-old “flabby” tragic antihero who is in a sexless marriage and has devoted his life to Jesus. He addresses an open audience, telling us he’s “totally committed, in my own way, to becoming a saint”; and yet, he’s just like us, with the same quotidian troubles: “Saints don’t ask their parents for loans … But I wanted to change jobs. I absolutely had to change jobs.”

He works at Non Possumus, a “far-right Catholic publishing house” that plays a “distinct role in the internal debates of the Church … Who else talks about the cultural power of the Jewish lobbies in Europe and America, their dechristianizing efforts?” It’s an anti-Semitic publishing house, but Rosini rationalizes, “the times being what they are, you don’t turn up your nose at a chance to earn a living.” One time I worked as a makeup artist for child actors.

Non Possumus’s current project is a book purporting John Paul II was secretly Jewish, aptly titled The Jewish Pope. (Entertaining aside: Before The Jewish Pope, Non Possumus published The Book of Cocks, proving that “producers had inserted nudity into children’s movies and cartoons in the form of photographs or drawings of breasts, vaginas, and penises, as new single frames or montaged existing ones.”) Non Possumus refuses to publish novels, an ungodly genre.

For the first half of the book, Rosini rattles off a litany of cultural toxins in descriptively baroque paragraphs—but not to warn readers against them or offer treatment, not to make any point other than to talk shit about dark times where entertainment and art take us away from accessing a deeper part of ourselves, hijacking our connection with God. There are long philosophizing passages—about the church, about cunts, about nature—that don’t enlighten so much as provoke. Our narrator says stuff like: “Certainly, after 9/11 my world of ideas, of pleasure, of books, had collapsed a bit like the towers.”

I’m paraphrasing Mary Karr and David Foster Wallace when I say literature ought to be a service to a reader’s interior life. I read to feel, to be moved, to live a more engaged and aware life, to have an emotional response I don’t get from sitting at a computer eight hours a day. This is my hope in literature, that it will alter and improve the way I view and interact with the world, that it will in some sense rescue me.

“The truth can’t be found in novels!” Rosini says, explaining why he stopped reading them. As with most things Rosini says, I don’t agree.

The first “turning point” in Rosini’s life is meeting Corrado, an aspiring novelist who pitches Rosini his novel about a gay couple that wants a traditional family. Rosini pontificates to Corrado how Italy is full of aspiring writers: “I’ve seen so many … illiterates who use too many ellipses … You know that you shouldn’t ever use more than one question mark?” These meta-moments are the best—self-aware, funny, genuine.

Corrado introduces Rosini to Lavinia. One night at a bar, Lavinia places her legs on Rosini’s left thigh, at which point he throws his chaste thoughts out the window. When he talks about sex (not celibacy), both the narrator and prose come alive: “When you start having sex you discover new lifestyles and forms of art, entire continents and alternative vocations, new ideologies and ways of falling asleep, breakfast menus, combinations of amusement and mystery.” Turning point No. 2.

Rosini doesn’t know what he wants in life or out of life, and these ambiguities launch a familiar ennui and panic that drives him from Rome. Sans job and chasing Lavinia, he flees to Paris, where he interns at Éditions du Bac and lives rent-free in the adjoining flat. His wife doesn’t follow, and yet they don’t divorce. It’s complicated. Ostensibly he’s avoiding the public outcry when The Jewish Pope is published.

Instead of working hard, he takes a lot of strolls in Paris, searching for Lavinia. (Spoiler: He never finds her—is this some post-modern technique or just sloppiness?)

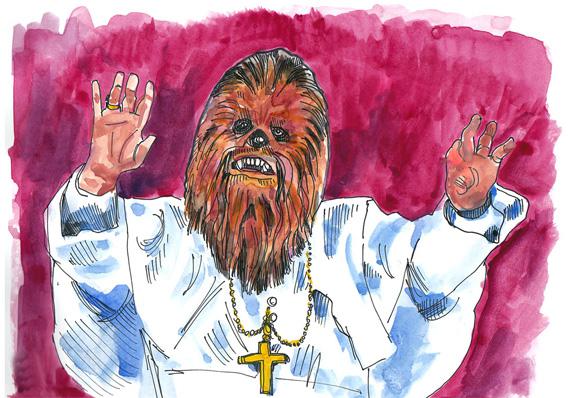

In Paris books are no longer bullshit. “Corrado’s novel had renewed my love of literature, Lavinia my love for the human species, prompting me to reread the stories that had formed me.” Novels are a slippery slope. One day he wakes up with an erection. Next he masturbates. He explores Internet porn. One evening he meets “a quartet of female bourgeois bohemians” tripping on MDMA who change his life. Again. He tells them his name is Chewbacca as he thinks of himself as “an enormous, hirsute Cinderella, a listless, sweaty insect.” With them he gets drunk and smokes hash and forgets his wife.

Among the group is Clelia, an art gallery assistant and a Jew. Clelia connects “Chewb” with Uncle Leo (also Jewish), who rents various apartments in Paris and offers one to the enormous, hirsute Cinderella. With his internship almost up, he accepts. Leo begins calling our narrator “Rosenzweil.” We’re up to at least two alter egos.

Photo courtesy of Grazia Ippolito

With his new persona, he seduces Clelia, who hardly needs seducing. Unbeknownst to Leo, Clelia spends most of her nights at Rosenzweil’s place. It’s not what you think though—unless you think that a celibate married man devoted to Jesus would live with another woman and never touch her sexually unless she is asleep. Because that’s what he does. But in this book it’s fine to cheat and molest if you’re a split personality. When Clelia returns Rosenzweil’s touch, he calls it a “Jewish caress”; he refers to her as “the Jewish girl,” “the Jewess at home,” “this Jewish mouse.”

Sinister, untrustworthy, egomaniacal, it’s hard to like the narrator who talks like this, who says things like, “Of my Roman weekend there’s not much to report,” like we care. How can we care? As a Jewish girl, I broke a pen while stabbing the book so many times with it. (It’s certainly been an interactive reading experience.) At these moments, I feel robbed of the pleasure I take in reading, of connecting with the characters and entering into a meaningful conversation with another (neurotic) mind.

“[T]his was not the story of my redemption, but neither was it merely a story of my depravity,” Rosini or Chewbacca or Rosenzweil says. “I wasn’t someone who had repented of having thought ill of Jews and now that he knew them didn’t find them so bad.” So what is the story about? At one point Rosini describes Clelia as someone who “didn’t speak from the heart; instead she spoke ironically.” This is a fitting description of our narrator, whose unceasing ironic detachment kept me from any intimacy with him and from any Great Truth about his story. “Irony has only emergency use,” wrote Lewis Hyde in Alcohol and Poetry: John Berryman and the Booze Talking. In his essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” David Foster Wallace expounds:

“This is because irony, entertaining as it is, serves an almost exclusively negative function. It’s critical and destructive, a ground-clearing…singularly unuseful when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks.”

Yes. Emotional generosity, sincerity, and clarity are the virtues of literature. What is Rosini’s true voice, his earnest opinion? Without knowing, he hasn’t said much that is significant. He blames novels for filling his brain with bullshit, but he’s mistaking the cure for the disease.

Spoiler: Things don’t end well for Rosini/Chewbacca/Rosenzweil. When The Jewish Pope is published, Leo discovers Rosini’s anti-Semitism and ends their friendship. Everything unravels from here. Rosenzweil begins to multiply, the narrative splinters and offers a picture of the mind in flux, at the limits of sanity. There’s Rosenzweil Two, Three, and Four. It’s a lot like the movie Multiplicity.

Rosenzweil thinks he might have avoided his downfall by having sex. “Too late: I didn’t fuck [Clelia] before the book came out and now the damage was done,”; this is followed by pages and pages of italicized “ifs,” Rosenzweil tracking thoughts to their improbable end, imagined journeys to nowhere, including one where he takes MDMA. “I have never been so absolutely happy in my life,” he says, and it’s a relief. But it turns out to be just another fantasy.

“But what’s the point of these internal struggles?” wonders Leo in the last chapter. I have the same question. Perhaps the point is there is no point (how post-modern), that we all have novels and fictions inside us—even the most vile and superficial of us—very possibly mediocre novels where not much progresses and there is no great awakening, where characters come and go without explanation and most don’t like you, where amid the noise and disappointment of the modern world, we go inside our heads and stay there, preferring our life to be a collection of stories we tell ourselves. “[T]he life of Piero Rosini had always been rhetorical,” Rosini concludes.

The Story of My Purity is a collection of anti-Semitic rants, sexist remarks, and societal denouncements; but it’s also an angsty rumination on the difficulties of being an adult—finding a desirable partner, a meaningful job, a place in the world—and an in-depth narrative on the precariousness of faith and fidelity, the price of pleasure and distraction, the prison of self-consciousness, the limits of fantasy and happiness, the scope of loneliness, and the power of the life of the mind—in short, this book is our story. The narrator is a lot like us, and I hate him.

—

The Story of My Purity by Francesco Pacifico. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.