White men can’t dance, black men can’t swim, and Asian men …

Martin Luther King Jr. said we should be judged by the content of our character and not the color of our skin, but no one said anything about what’s in our pants. There is an unspeakable fallacy that all Asian-American men must decide early in their adulthood to acknowledge or not, one that concerns their manhood. Call it the elephant in the men’s room. An Asian elephant that America believes has a small penis.

What’s changed, maybe, is that this archetype has somehow become acceptable, even trendy. (See: black resin glasses, comics, obsessive collectioneering, geek chic, nerd-core, backpack hip-hop, nouveau japonisme.) Still, it continues to imply a lack of sexuality. Rarely does the Asian-American guy go home with the girl—and the injustice is doubled when his female counterparts are pathologically fetishized.

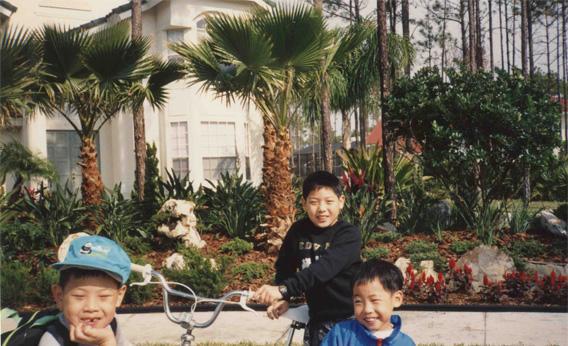

Eddie Huang’s new memoir Fresh Off the Boat suggests it’s up to the Asian-American man to pulverize his sexless image with hip-hop, fresh apparel, and authentic Chinese food. The book, and the life it documents, is an unapologetic attack on the Asian masculinity fallacy. It implicates everyone: from Huang’s closed-minded white neighbors where he grew up in southwestern Florida, to girlfriends who turn his would-be cohorts into milquetoast civil servants, to his parents for their misguided attempts at making him an upstanding dork. (They succeed only in teaching him that he must be more discreet in his aberrance.) But the message is clear: America has an unfortunate tendency to neuter Asian-American men, and Eddie Huang won’t take it lying down (unless “it” is America’s girlfriend).

The fact that Huang has initiated (some would say instigated) debate, conflict, and several full-blown fights in the world of New York high/low cuisine challenges the model minority myth, which would have Asian-Americans pushing only when shoved. Pushing/shoving/general mayhem makes up much of the memoir’s Part 1, which spans Huang’s early childhood up through early adulthood. During this time Huang drops out of college (to later complete his degree at a “lesser” school) and lands in jail twice: once in high school for throttling a classmate poised to beat up his brother Emery, the second time for crashing a Chi Psi frat party with an alleged concealed weapon. His coming-of-age scenes are always battle royales. One time, the Huang brothers confront a group of Indian boys from the neighborhood—Eddie’s grievances are obviously not exclusive to white Americans—who’ve parked a car with a vanity plate reading “AK-47” on the Huang driveway and lawn. Eddie (in high school at this point) gets clocked in the face; 8-eight-year old Evan (the youngest brother) comes out of the house shooting at the Indian kids’ car with a paintball gun; Emery eventually chases one of the boys with a pitchfork. As a kind of self-help guide for the neutered Asian-American male, the laugh-out-loud memoir mostly concerns itself with Eddie’s rock-star delinquency. Still, one can’t help but wonder—fear, almost—how the other Huang brothers turn out.

Part 2 begins with a hajj to Taiwan, and it’s a meditative break from the video game pace of young Huang’s mischief. Though the trip is part of a “Study Tour” program, Eddie believes his parents have sent him to Taiwan to “go home, see the motherland, and, eventually, get someone from the same tribe pregnant” while the effects of his second arrest cool down in Florida. He returns to the United States refreshed and even more confident—and immediately falls back into a whirlwind of deferred careers. An attempt to write for the Orlando Sentinel’s sports section is quashed by an editor who flatly tells him he can’t guarantee work for someone with “that face.” He goes to law school and briefly works for a Midtown firm. After getting laid off, he funds a new set of goals with gray- and black-market dealings in imported sneakers and weed.

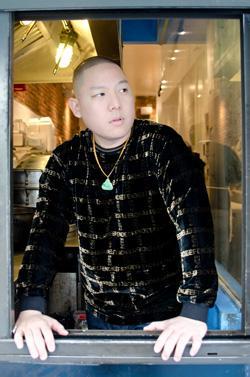

Opening a restaurant was the last bullet point in a six-month action plan to kickstart his life post-being fired. (The list started with quarterbacking for the Redskins and playing for the Knicks.) What eventually became Baohaus, though, was Huang’s version of owning up to his own arguments about ethno-culinary authenticity. From Page 1, which describes his grandfather complaining about imperfect dumplings, it’s clear that Huang does not want heritage cuisines to be taken for granted. Instead, they should be vaunted by the people they represent. So he made Taiwanese gua bao (steamed pork bun sandwiches) the hallmark of his new business, even though he admits to not being the dish’s biggest fan. Slinging what amounts to a Chinese barbeque pork sandwich is a strategic marketing move: White America likes sandwiches, and damned if char siu bao isn’t close enough.

Delinquency can seem endemic to memoir-writing—though there is no indication either in the memoir or in real life that Huang has learned to stop antagonizing people. Recently, he started a public celebrity-chef spat when he accused Food Network hero Marcus Samuelsson of contributing to the gentrification of Harlem by opening Red Rooster, an upscale soul food joint. In his op-ed review of Samuelsson’s memoir, Huang attacks Samuelsson for willingly playing to tokenism—to what Michael Twitty of Afroculinaria calls the “one negro syndrome”—and for “writing the report on a book he never read.”

For Huang, race and cuisine intersect too often in a bourgeois white bubble. His gadfly/bête noir persona has earned him more followers than enemies, perhaps because authenticity can appear an Asian’s only defense in a food culture rigged for Food Network superficiality and prêt-a-manger “ethnicities.” It’s no wonder Huang files grievances both against said network (after losing to what he believes is a more telegenic competitor on Ultimate Recipe Showdown), and Asian-Americans like David Chang, whom Huang has challenged to several culinary (and one fitness) battle. Chang’s crime is being a sellout. Whereas Huang’s more explicit philosophy on race and cuisine would be, in the words of one of Huang’s idols Tupac Shakur, “Ride or die.”

It is worth noting that Huang’s offensive comes as Asian-American men start to infiltrate a category of manhood that hasn’t been available to them since Bruce Lee. This manhood has accrued the descriptors jock, or meathead. A pejorative when applied to other races, when it concerns the ever-elusive Asian masculinity, the image is almost endearing. As Huang has been declaring at events recently, Fresh Off the Boat “is the beginning of a movement of big dick Asians.”

His concern with the myth of Asian phalluses goes way back. “My cousin Allen was the first to point it out to me when we were still kids,” he explains.

“Yo, you notice Asian people never get any pussy in movies? Jet Li rescued Aliyah, no pussy! Chow Yun-Fat saves Mira Sorvino, no pussy. Chris Tucker gets mu-shu, but Jackie Chan? No pussy!”

“Damn, son, you right! Even Long Duk Dong has to ride that stationary bicycle instead of fucking!”

Photo By Steven Lau.

Then, as a college student, Huang tries to get out of officially joining his school’s Asian student union, which he accuses of subscribing to a model minority myth. His emblematic problem with the “bamboo ceiling” they all embrace is that “Jet Li gets NO PUSSY!” in Romeo Must Die.

Huang is arguably better known for statements like this than he is for his cooking. As the host of a ViceTV show, Fresh Off the Boat With Eddie Huang, he’s become a pop anthropologist franchising relationships between Asian Men 2.0 and the rest of America. In the show’s second episode, Huang orders a German bratwurst dish at a Taiwanese café that serves food in miniature toilets. The sliced sausage is festooned with a brocolli floret, which obscures the meat. Cue a veiled, metaphorical lesson on making the best of a bad situation (small Chinese sausage) by trimming the shrubbery (i.e. don’t bother covering up the sausage with broccoli).

While on ViceTV Huang may show how to be a Big Dick Asian by way of example, in his writing and stand-up—Huang was a stand-up comic in between selling clothes, practicing law and running a restaurant—he does it by piggybacking on the more virile stereotypes of black men. Huang describes part of his comedy philosophy as an experiment in stereotyping. By exchanging tropes of the emasculated Asian male and the “dick-swinging” black man, he demonstrates that all stereotypes are volatile and irrelevant. One could argue though, that he fetishizes the black size myth to neutralize the Asian one. Amid references to hip-hop and gangster rap, the author fantasizes about an America that fears the mentally unstable Asian-American man, just as it fears black male anger. In a set he calls “Rotten Banana” he exclaims, “White people weren’t scared of kung fu, but you know what they were scared of? Black people! …. THEY’LL FEAR US!” He even suggests that the stigmas of black culture “could be used to empower Asian and Arabic people who had been considered model minorities.”

Huang’s success as a restaurant owner is matched only by his storefront antics—hiring employees through obscure hip-hop references posted cryptically on Craigslist, getting blitzed the night before a New York Times review, antagonizing patrons who insist on bespoke versions of a fixed menu of Bao pork buns. He’s not just fucking around; he’s trying to rewire assumptions about the Bulletproof Chinese Food Vendor, one of Asian-America’s least understood stereotypes.

Because while Fresh Off the Boat’s celebration of the success of a young and charismatic New York restaurant owner may obscure the message, the fact is these kinds of success stories are minimum entry for Asian-American acceptance. An Asian kid opening his own business and “making it” is about as shocking as a black power forward. If hyper-masculinity is the new frontier for Huang, a sense of boredom with the model minority trope was the gateway.

He’s not the only one getting restless. Missives like Fresh Off the Boat come on the tide of a critical mass attempting to blow up the status quo. Wesley Yang’s “Paper Tigers” for New York magazine abolished the notion of a model minority with loud yawns of boredom. Carolyn Chen’s New York Times piece “Asians: Too Smart For Their Own Good?” negotiates for the end of affirmative action policies that punish good work by taking Asian performance for granted. If the fallacy of the Asian male has gone unchallenged in the media, it has at times been cannibalized by the Asian-American woman. Jenny An’s “race trolling” piece for xoJane.com, “I’m an Asian Woman and I Refuse to Ever Date Asian Men,” may have outraged the larger public, but it arose from a broadly acknowledged problem with interracial dating: Asian-American men supposedly “lose” every time. (Ask Jet Li.)

Huang’s memoir has the self-indulgence of comeuppance rap and the tempo of a stand-up routine, with citations ranging from Nas to Jonathan Swift, as if the author’s in a hurry to prove something. (The size of his phallus, explicitly.) Between junior high and college he is tossed by and tosses around enemies, strangers, and even family at a rate that makes him come of age at least once a year. So no, his memoir is not a traditional immigrant’s tale. It is an anthem. For if the unspeakable fallacy is that Asian men have small penises, the crime against Huang’s humanity is that Asian men haven’t been allowed a proper phallus. That phallus is to Asian men what a college education is to the underprivileged, and Fresh Off the Boat is affirmative action into “plates and plates and plates of titty.” This is about, in other words, a Big Dick Asian suiting up against the status quo and rallying his “chinkstronauts” to venture with him into the great unknown—because this is America. Because in America, it’s not the nice guy who finishes last. It’s the guy who has to believe size doesn’t matter.

—

Fresh Off the Boat by Eddie Huang. Spiegel and Grau.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.