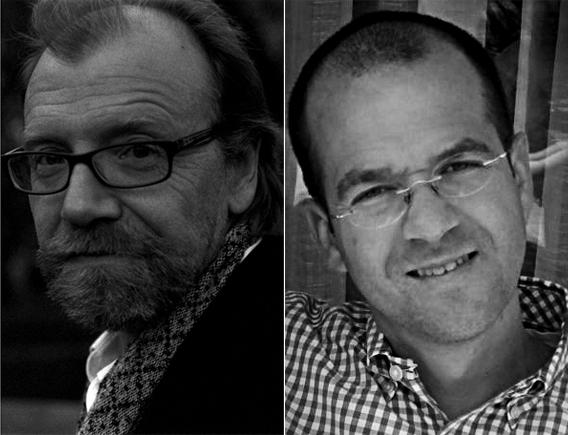

Andy Ward has edited George Saunders’ writing since 2005, first at GQ, and now at Random House. On the occasion of Saunders’ new collection, Tenth of December, Ward and Saunders emailed each other about writing, editing, outtakes, and how over and over again The Novel becomes a story.

Ward: Correct me if I’m wrong, but there’s a story in this here collection, “Semplica Girl Diaries,” that you started in 1998 and finished in September of 2012, 14 years later.

Saunders: Yes, and thanks for bringing up that painful subject.

Ward: Hey, at least I didn’t ask you when you were finally gonna write The Novel!

Saunders: Actually, at least three of the stories in this book were “novels” until they came to their senses. That seems to be the definition of “novel” for me: a story that hasn’t yet discovered a way to be brief.

Ward: OK, but at one point, I think you said “Semplica Girl Diaries” was almost 200 pages long. When you sent it to me—with the caveat that “this story has confused me for many years now”— it was about 30 pages long. Is this normal for you? It brings to mind a story I once heard about Robert Rauschenberg, I think, who was asked, “How do you know when a painting is done?” And he responded, “When I sell it.” Do you feel the same way, that you could keep reworking things forever?

Saunders: “Semplica Girl Diaries” was unusual in the time it took but not in the pattern. I’ll often get stuck in the middle of something like that. What happens is that I start out pretty well and then “figure out” what the story is about—but the danger is that the story will just be about … that. So there can be a period where I’m waiting for the story to hop up to another level—but to get that to happen takes me a lot of writing.

As far as Rauschenberg—I have an internal standard for when a story is done that I can’t really articulate. Maybe it’s just: I know it when I see it. Or: I know it when I don’t see it. It has something to do with making the action feel undeniable. There’s a feeling I get when (in the rereading) the language passes over from language to action: What was mere typing before starts to feel like something that has actually happened. So that can take a while and it’s not just about the language—it’s also a structural thing. If the story is tight and all the scenes are necessary, it helps me to understand what the current section is supposed to be doing—and hence I can know when it’s right and done.

One thing that really helped on this one was your patience—as we went down to the wire, the story still kept opening up and I appreciated how positive and supportive you were—no pressure, all hope. A perfect atmosphere in which to write.

Ward: A lot of people say to me, “God, it must be so fun to work with George Saunders. Do you even have to edit him at all?” And they say it like they assume you shun all editing, or don’t allow editing, which is always really funny to me, because you are a person who craves feedback, who wants to be pushed and challenged and sent off in new directions. This all sounds self-serving, I realize, so I should add: Of course, at this stage, you don’t need an editor. But you want an editor. Why?

Saunders: No, I definitely need and enjoy having an editor, and for the exact reasons you state. There’s a really nice moment in the life of a piece of writing where the writer starts to get a feeling of it outgrowing him—or he starts to see it having a life of its own that doesn’t have anything to do with his ego or his desire to “be a good writer.” It’s almost like an animal starts to appear in the stone and then it starts to move, and you, the writer, are rooting for it so hard—but may not be able to see everything clearly after working on that stone for so long.

If a writer understands his work as something that originates with him but then, with any luck, gets away from him, then what he needs is someone who can grasp the potential of the piece and lead him to that higher ground. (I’m aware I’m mixing metaphors here. OK: One ascends to the higher ground, and on that higher ground is a sculpture of a bear, a bear that is “coming alive” and “outgrowing” him. And the editor is encouraging him to “grasp the potential of” the bear. Aiyee.)

One of the things that you are really great at is simultaneously acknowledging the parts that are working and showing me to the places where the piece could be working better—it’s a genuine kind of encouragement that is literally “en-couraging”—it makes me feel, “OK, I can do this, Andy likes Part A and Part B, so I can go back to Part C and find a bit more in it.” There’s also a way that you have of being precise but also allusive, that works well for me—it’s something about the open-hearted way you frame your queries. Instead of feeling daunted or discouraged, I feel excited to give whatever it is a try. This takes a lot of editorial wisdom and confidence—to know just how to get the writer to take that extra chance.

Ward: It’s easy to acknowledge that parts are working when the parts are working! I never strain to find passages in your work where I can write “I love this” in the margin and really mean it. But it’s also freeing, as an editor, to know that your partner in the process—the writer—is so open to suggestions, and to reworking things, and pushing deeper into an idea, or a scene, that might seem good enough as it is. I never get the sense that you don’t want to be bothered to make something better. And I often find that you have a pretty good sense of what I’m going to say, anyway. Like, I’ll put a note in the text that says, “I’m not sure this graf is working, or adding much. Cut?” And you’ll say, “Yes, cut, and I kind of knew it wasn’t working, too.” That kind of similarity of sensibility/worldview takes a lot of the tension out of the editing process—which I always feel shouldn’t really be a tense process if both parties are coming to it honestly and with good intentions.

You and I have talked a lot about how this book feels a little different than your previous collections. The voice has maybe come down an octave here and there, the emotional stuff simmering beneath the surface is, for me at least, harder to ignore. Can you articulate why that is? Was this a conscious thing?

Saunders: It wasn’t exactly conscious, I don’t think, because the book came together over such a long time. It might have just been developmental: I got older and moved into a new stage of life. And in that new stage, things look different. But I think the most truthful explanation is a little more technical. I would come to some fork in the road in a story and it would seem that certain choices weren’t interesting, in part because either I’d done them before or had seen them done before. So in order to keep interested I’d have to swerve in a new direction, and that direction often tended to be … (and here I’m struggling for the word, so as not to sound full of it) … but maybe … well, I found myself trying to avoid what we might call the “knee-jerk negative swerve.” Or “the choice that indicates humans are always shit.”

I turned 54 this year and I find myself feeling like I’m in a bit of a race to get down on paper the way I really feel about life—or the way it has presented to me. And because it has presented to me very beautifully, this is hard. It is technically very hard to show positive manifestations. (“Happiness writes white,” said de Montherlant, who was, Wikipedia told me when I just now went to find out who’d said that, a Nazi collaborator.) But I can look back at the way I thought and felt even as a little kid and there was a lot of wonder there, and openness to the many sides of life—the way that beauty and ugliness co-present, for example, or the way that tragedy might be enshrouded in something really funny, or vice versa—and I feel like I’ve only barely scratched the surface so far in what I’ve been able to write. And I have finally realized that, you know, it’s not a given that my lifespan will accommodate my writing aspirations. It could be that it would take me 12 more books at six years each to get it—which means I would have to live to be 126. Which I fully intend to do, of course. But it seems to me that there are certain thoughts and vignettes and attitudes that I have always had the desire to represent—but that I’m only now picking up the chops and/or confidence to pull off. So, good news/bad news: good news that I’m progressing; bad news that life is short and art is long.

Ward: Let’s talk about nonfiction. I spent 15 years in magazines, editing stories, and I never encountered another writer who worked like you. Your drafts were incredible. You delivered a version of the story—often a little longer than we’d anticipated, but still: Jesus—and a companion file of “outtakes.” This file consisted of 2,000-3,000 words of perfectly polished sections you had taken out of the story, and yet, obviously kind of wished you had kept in. Otherwise, why the crystalline outtake file? What a beautiful system. So the process, for me, became merging documents, essentially: picking my favorite outtakes, and working them into the final story. How did you come up with that system? I noticed you also do it with some of your short stories, too. Isn’t it hard to put something back into a story once you’ve taken it out?

Saunders: It’s a little like packing for a trip. First you lay out everything that might possibly be useful, with no thought about the size of your suitcase. Then, look at your suitcase. In the case of narrative, there’s a certain obligation to keep the pace up and have each section or subsection be doing something. The ideal thing would be: no merely decorative sections. Every section has to (1) be good in its own right (funny, or sad, or fast, moving, whatever) and (2) advance the story in a meaningful way. With that criteria in mind, some bits are just … goiter-esque. Even if they’re good. If they’re not functional, they’re optional.

So with the GQ pieces, which I knew couldn’t be much longer than 12,000 words, there always came a draft of reckoning—where it suddenly became clear that entire vignettes (which were actually pretty good, i.e., pretty well-realized) would have to go.

Then usually just before sending I’d cull through all of the stuff that had been cut, and start editing that as well—trying to get each bit down to the bare minimum, or the essence of itself, so to speak. And as I kept working (trying to get down near 12,000 words) I would keep cutting from the good bits and whittling down the rejected bits, thinking: If you guys are ever getting back into the story, you are going to have to be really lean.

So I would send you the outtakes in the spirit of putting out a fishing hook—the ones that you would call out as being good or possible, I’d try to work extra hard to get back in—sometimes they’d have to bump out some other bit. And sometimes you would say: This bit has to go in. Or send the merging document you talked about. So it was a form of gut-check. Like, I could make a really ruthless cut if I knew that you would eventually see the cut bits and call me on it if I was being too Draconian.

Ward: Do you still get that panicky feeling in your stomach when you send a story to an editor?

Saunders: Yes, and I hope I always do. I think that’s a respectful way to feel. A realized piece of writing had better be taking some chances, and since the end goal is communication, there’s always the possibility that the chance you are taking won’t pay off, i.e., the little leaps of faith that you’ve programmed in might be wrong, due to some tin-ear syndrome on your part.

Ward: Relatedly, do you ever not know if something is good at this point in your career?

Saunders: I feel more certain of what’s good, I think. Or—I know the trajectory of my own work through the many drafts, and can tell as I’m getting closer to the place where it will be as good as it can get. It reminds me somewhat of when I used to work in my dad’s restaurant. After your 50th dinner rush, you started to get a feeling for where you were in that process. It would be a total madhouse but, remembering the previous total madhouses, you could go: OK, we just have to hold out for another 15 minutes and it will recede. So sometimes in a story I can feel that it’s not working yet but at the same time can feel it slowly moving in the right direction. And can have some idea of how long it will take before that version of the story will show its true face.

Ward: OK, let’s do a speed round. I’m gonna throw out some topics and you give me 20 or so words off the top of your head. Ready?

Saunders: Ready.

Ward: CivilWarLand in Bad Decline.

Saunders: A book, written at work, by a youngish guy just realizing that capitalism can suck (i.e., can “plunder the sensuality of the body”).

Ward: The process of writing: Is it agony? (I think of the Post-it Philip Roth put on his computer, post-retirement, which read, “The struggle is over.”) True for you?

Saunders: I’m not sure I would call it agony but there is a kind of cyclic frustration. You get one story right and then here comes another one. When does that end? What I’m trying to do is get it to end right now, by recognizing that that cycle is writing. That is: trying to understand the frustrations and setbacks (and agony) as part of a bigger chess game you are playing with art itself. If someone really loved boxing, I suppose that when he got really nailed part of his reaction night be: “Huh, interesting—I wonder how that happened? And how do I prevent that from happening again?”

Ward: Your essay collection, The Braindead Megaphone.

Saunders: Sold enough that I got to go on TV, which helped me realize I should shy away from being on TV and just write fiction.

Ward: Your new book, Tenth of December.

Saunders: A book I would have liked to have written when I was young but didn’t yet have the chops necessary.

Ward: Why is that? Is it a matter of wisdom simply coming with years, or that you have gotten better as a writer? In other words, what did you not know then that you know now? Easy question, right?

Saunders: I’ve always wanted to write energetic, atypical sentences, i.e., sentences that were not normal or bland. I used to feel that there were situations and actions and mind-states that were too “banal” for me to describe them well. Now I feel that there is nothing that can happen to a person that is banal. Feeling that way was a failure of vision on my part. Everything that happens to us is interesting. That’s our job: to feel that way. And an interesting thing has started happening: feeling that way (or at least trying to feel that way), I am finding that non-banal prose will always present itself. Or the prose is banal at first, but if you start poking at it, with the confidence that the underlying reality is not (is never) banal, then the prose starts to rise to the occasion.

Ward: Favorite non-Saunders story ever.

Saunders: “The Overcoat,” by Gogol.

Ward: Favorite Saunders story ever? (Mine is “Tenth of December,” with apologies to “Pastoralia.”)

Saunders: Part of the process of moving on and doing more work is to regard all past stories as these small clay rabbits you have made and brought to life, which you loved very much during that process, but which then go running off across the barnyard into the mist, with your blessing. So no favorites. I just feel slightly fond of them all.

Ward: The role of fiction.

Saunders: Transfer energy from writer to reader.

Ward: The role of short fiction.

Saunders: Do that quicker.

Ward: Realism.

Saunders: Realism is to fiction what gravity is to walking: a confinement that allows dancing under the right circumstances.

Ward: Your reputation as a satirist.

Saunders: Slight thorn in my side.

Ward: The word “genius.”

Saunders: Always good for a laugh around our house, like when I accidentally drop my phone in the shitter.

—

Tenth of December by George Saunders. Random House.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.