Peter Trachtenberg’s Another Insane Devotion is a discursive essay on personal growth, a public exercise in private exorcism, and a collection of notes toward a philosophy of love. Pondering morality and memory, the author addresses Sappho, Homer, Aristotle, Descartes, Michelangelo, Proust, Ruskin, and the Gnostic gospels. He argues with the universe, anatomizes exes, dons a hairshirt or two, and by-the-by sketches Hopper-esque scenes of small-town strangeness and urban alienation. The book inspired many thoughts in me, foremost that I need to clean the litter box. Another Insane Devotion is a cat memoir.

Would meowmoir work as a coinage? Is there need of a coinage anyway? After all, though the Internet loves to laugh aloud at a fuzzy Felis catus, book publishing has declared the dog its best friend; as Trachtenberg observes, “It’s easier to write about a dog than a cat. With dogs, there’s always something going on.” It seems possible that with cats—excepting craps taken territorially in an infant’s crib—there is always nothing going on. Or, to steal an idea from an earlier meowmoir—Willie Morris’ My Cat Skip McGee—dogs are about doing and cats are about being, pure being.

Curled up in the sunbeam of Another Insane Devotion is Biscuit. Biscuit! Here comes Biscuit on the first page, ginger-furred and snot-faced, a female just rescued from the wild. The cat greets Trachtenberg with a possessive lick of the hand: “She was claiming me.” There Biscuit goes, on the third page, wandering off from Trachtenberg’s upstate New York house while he and his wife are away. Alerted of the crisis by a cat-sitter manifesting depraved oafishness, he spends money that he does not have to fly home from North Carolina and mount a search.

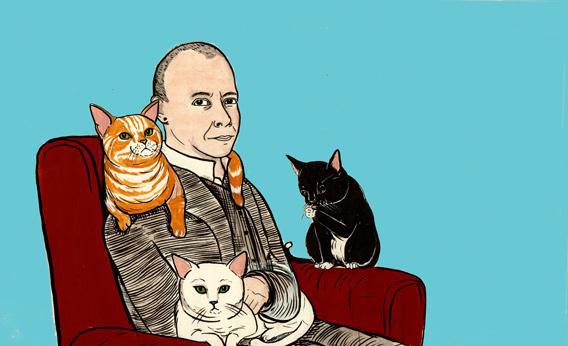

This quest constitutes the book’s centerpiece, a semi-suspenseful narrative maypole gradually wrapped in ribbons of digression, with the author telling the stories of his domestic life in self-aware circles, lit-critical coils, and downward spirals. It’s obvious from the jump that Biscuit is not the only one lost in a dark wood. Trachtenberg depicts himself as a bit of a stray, which perhaps explains his desire to take in so many of them. When Biscuit arrived, there was already a dementia-addled old tom named Ching and a black shorthair named Bitey. And then there was one-eyed Gattino, a runt born near a writers’ retreat in Tuscany. Trachtenberg and his wife (whom he calls “F.”) had lost Gattino the year before Biscuit wandered off.

Gattino disappeared like the promise of domestic optimism, and he haunts the entirety of the narrative. Also, he haunts the entirety of an entirely different narrative: F. is Mary Gaitskill, and she published an essay about the Italian cat in Granta. Is this a first? Has it ever happened before that both halves of a sundered literary couple have written about their pet? (Did Edmund Wilson ever own an actual bunny? If so, did Mary McCarthy ever boil it?)

The Gaitskill-Trachtenberg marriage has yielded a nuanced game of he said-she said. Reading their accounts side-by-side is like watching a version of Divorce Court where the bailiff doubles as a couples therapist and the judge actively encourages irrelevant testimony. Take a moment to admire the blame-game trick shot of a moment where Trachtenberg, taking credit for the name Gattino, curses himself for causing “F.” to bond with a sickly animal from across the Atlantic; meanwhile, Gaitskill claims that “Peter” wanted to call the cat “McFate,” and that she changed his mind: “McFate was too big and heartless a name for such a small fleet-hearted creature. ‘Mio Gattino,’ I whispered, in a language I don’t speak to a creature who didn’t understand words.”

I don’t know that I’d want to be married to the guy myself, but I think it’d be fun to hang out. Paging through Another Insane Devotion, I thought often of the bit in Catcher in the Rye where Holden identifies a truly good book as one that leaves you wishing the author were a friend you could call on the phone. This book belongs to a related category: It is truly not bad, and I wish I could have had the phone calls in lieu of the literary experience. Here is the intrinsic problem, compounded by the book’s meandering nature: The cats all blur together. It isn’t difficult to sort out Biscuit from Bitey from Ching if you pay close attention to their antics, but it is difficult to pay close attention to their antics, because they are another person’s cats, and I don’t even pay such close attention to my own. I love him in an atmospheric way, but I am not sure that were he a person he’d be the kind of person I’d want to have a beer with. I initially thought to write this piece in his voice, but it came out sounding, in its harrowing lack of affect, rather like The Stranger.

It is not clear whether Trachtenberg understands the essential sociopathy of the species. When I read that young Gattino had “a look of jaunty toughness, like one of those skinny Neapolitan kids who grows up to be a prizefighter or a gigolo,” I felt that Trachtenberg was trying to put one over on himself. The phrase catches a truth about movement and bearing and then creeps up on its little feet to a fib about mentality. You can hug an Italian playboy without his making that expression elsewhere described by Marilynne Robinson: “Her ears were flattened back and her eyes were patiently furious.” Ian McEwan somewhere has a good one along the same lines. Actually, come to think of it, there is a lot of well-observed writing about cats in the world. This is because cats’ preferred way of interacting with humans is being observed by them.

My cat is an 8-year-old tabby. As in “The Naming of Cats”—from Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, T.S. Eliot’s light-verse incitement to Andrew Lloyd Webber—he has three names. There is “the name that the family use daily”—that’s Wally. There is the “name that’s peculiar, and more dignified”—that’s Sir Walter Raleigh. I’ve always supposed that this would be the name on his registration papers, if such a thing existed for a cat born in the basement of a deli and delivered unto a couple newly living in sin.

I’ve no idea what his third name is. That’s an essential part of the existential deal. Eliot writes:

But above and beyond there’s still one name left over,

And that is the name that you never will guess;

The name that no human research can discover—

But THE CAT HIMSELF KNOWS, and will never confess

When you notice a cat in profound meditation,

The reason, I tell you, is always the same:

His mind is engaged in a rapt contemplation

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name;

His ineffable effable

Effanineffible

Deep and inscrutable singular Name.

I’ve always supposed that we adopted Wally with the motive of turning a rental apartment into a home and to give our shacking-up a firm foundation. This is not to suggest that a cat gives good value as a practice child (though in their idleness and hauteur, they are perhaps good surrogates for teenagers). Rather, the idea was to give the home a spirit. It is essential to remember that the domestic cat domesticated itself: We didn’t set out to tame it; it just one day showed up conducting itself confidently. Same M.O. as Tom Ripley. “One can assume that they settled down, made themselves as comfortable as possible, and went about their business,” Faith McNulty wrote in 1962’s Wholly Cats. “People, on the other hand, seldom have been willing to let it go at this.”

In Another Insane Devotion, Trachtenberg writes, “The pleasure of dog ownership is having an animal that speaks your language, or a language that shares many terms with yours, like Swedish and Norwegian. A cat doesn’t speak your language.” If you believe this to be true, then it follows that the pleasure of keeping a cat is a function of this language barrier, that aloofness, the feline cloak of effanineffibility. A cat is a riddle you never get the answer to. I scoop the poop of a common sphinx.