The answer is less obvious than you might think. Sure, you are familiar with your own scrawled to-do lists, or the brief missives you leave on the kitchen counter for houseguests or your spouse. Perhaps you take notes by hand in meetings (though if you’re like me you consult them only sporadically after the fact). But when was the last time you filled a page of foolscap—or Mead college rule, for those of us who’ve never been quite sure what foolscap is—with lines and lines of unbroken lettering, trying to express an argument or make a developed point? When was the last time you used pen and ink for writing, and not just for jotting?

The Missing Ink, from British novelist Philip Hensher, makes the case that it has probably been too long. Subtitled “The Lost Art of Handwriting,” the book is an ode to a dying form: part lament, part obituary, part sentimental rallying cry. In an age of texting and notes tapped straight into tablets, we are rapidly losing the art and skill it takes to swiftly write, with a pen, a sentence that is both intelligible and attractive. The time devoted to teaching handwriting in elementary schools around the globe has dwindled. Hensher opens his book with the plaintive question: “Should we even care? Should we accept that handwriting is a skill whose time has now passed? Or does it carry with it a value that can never truly be superseded by the typed word?”

Hensher has a dog in the fight. He makes reference throughout the text to various chapters that he has drafted in longhand—a process unfathomable to someone who is tapping out these lines in the Notes app on her iPhone at 4:58 in the morning. (That’s one advantage to our modern means of scrivening—you can do it at night in the dark without getting out of bed or waking your husband.) But Hensher is a man whose friends compliment him on his distinctive handwriting (and who reproduces perhaps a few more of these compliments in the book than is strictly necessary). Hensher is a man who composes on paper and has a preferred brand—and nib!—of fountain pen. In other words, he is quite unlike most modern humans.

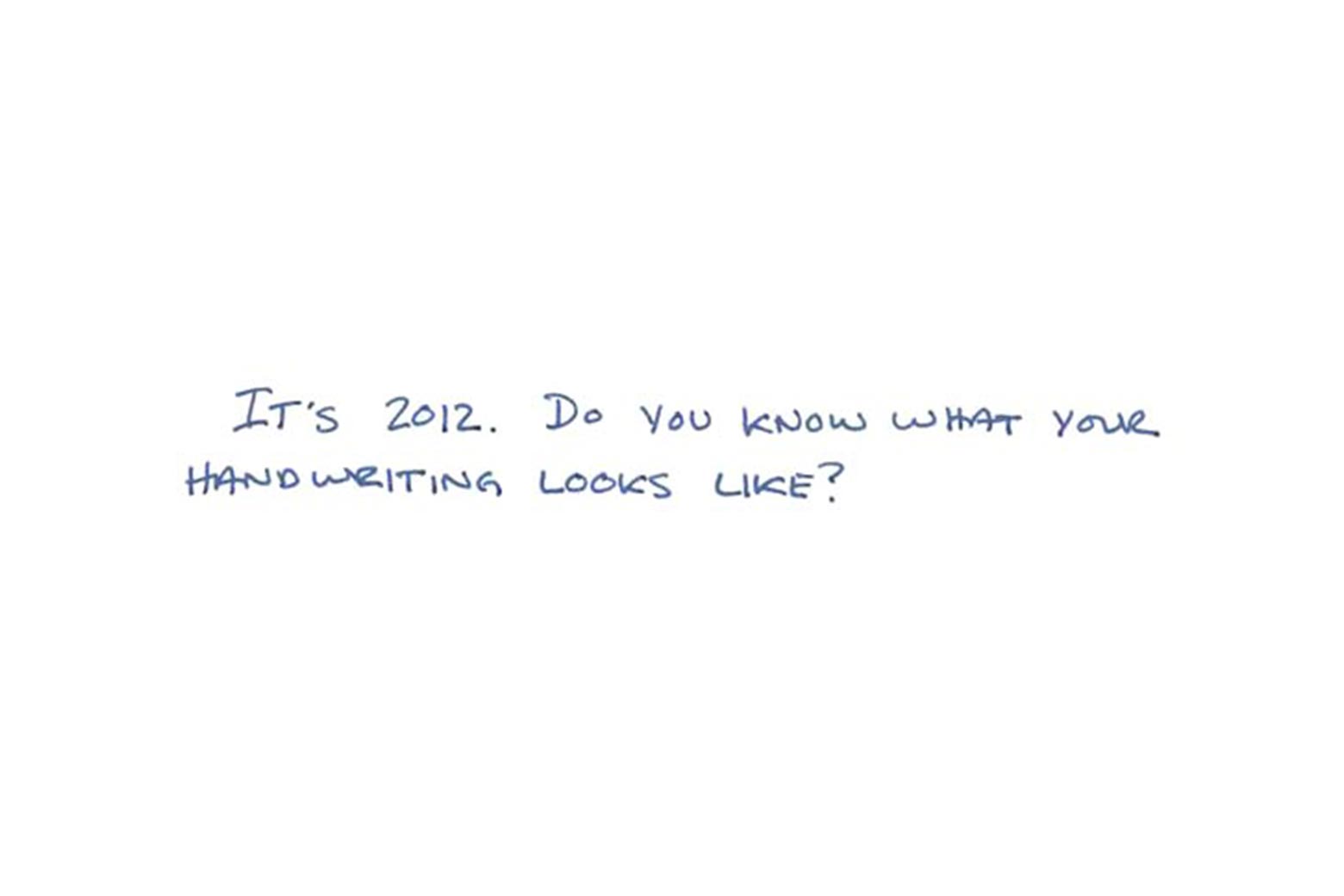

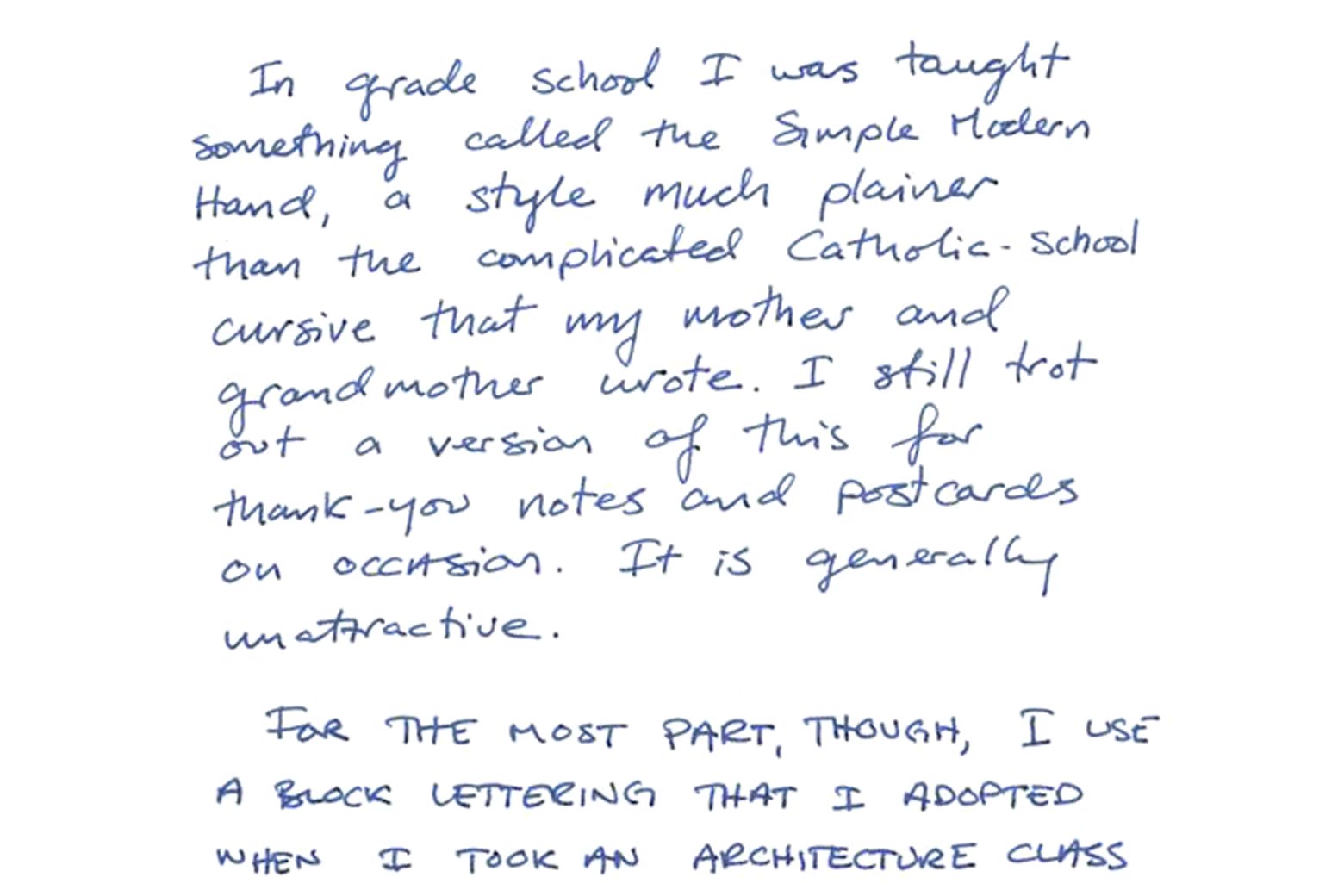

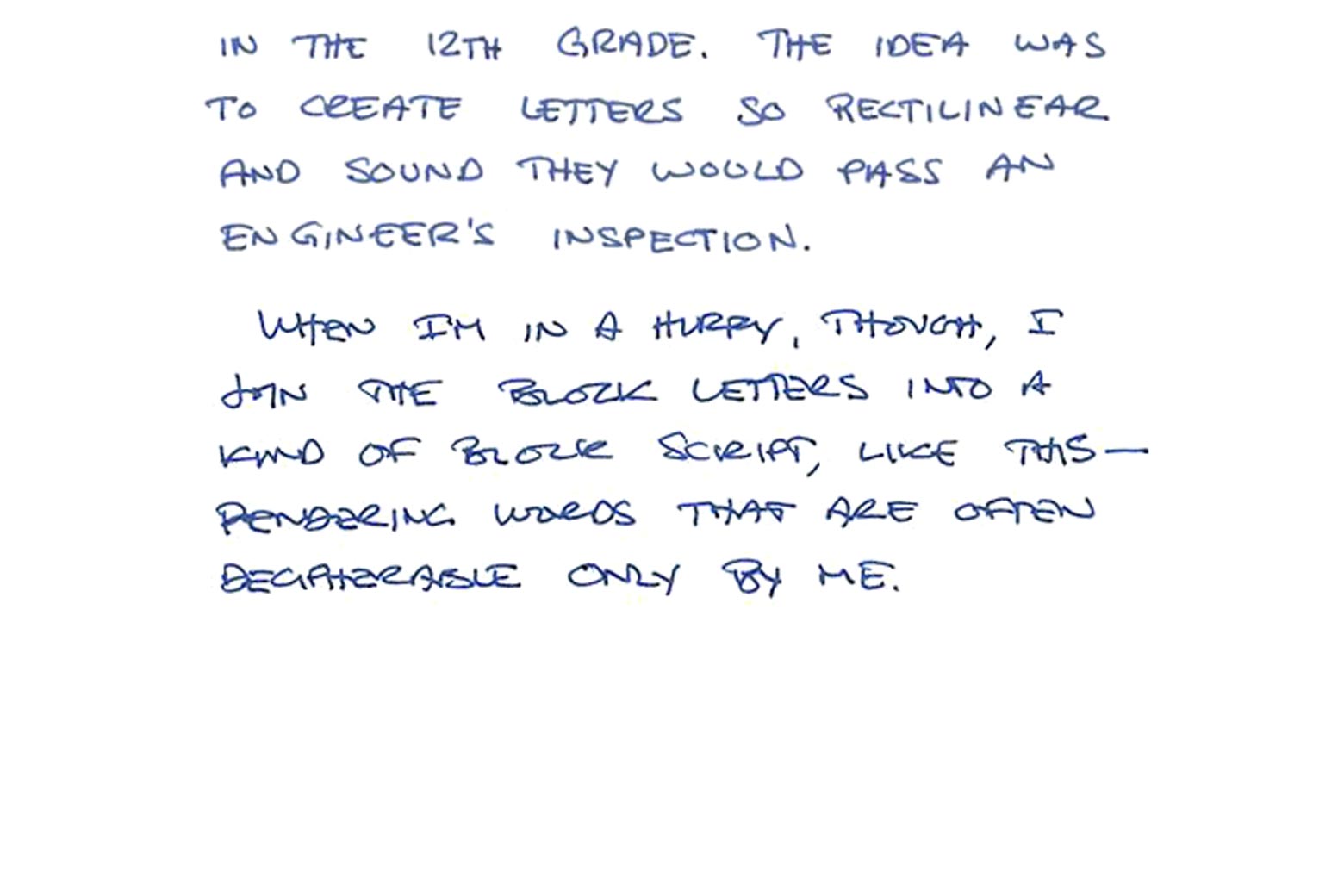

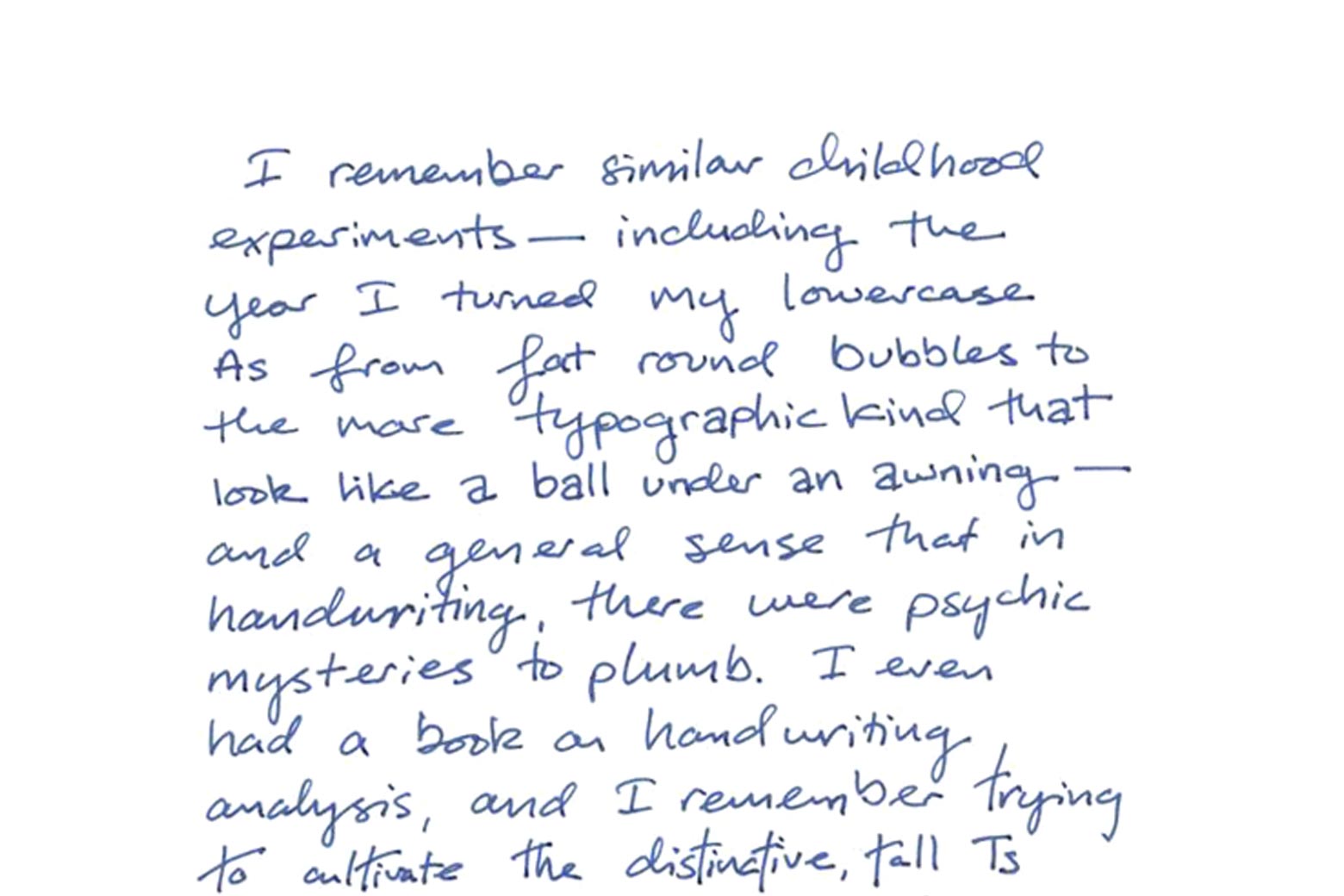

Still, I share Hensher’s concern about the “lost art of handwriting.” When I examine my own crabbed scrawl, I’m struck by the idea that I can no longer be said to have any particular sort of handwriting, anymore. Here’s what it looks like, these days:

When I review the 42 notebooks I have filled in my years working at Slate, they look like diaries of a madwoman—a jumble of styles and ink types with very little consistency. This is particularly troubling given Hensher’s emphasis on the notion that our writing is, on some level, an expression of ourselves. He is most eloquent—and his novelist’s eye for detail most keen—when discussing the self-consciousness with which young people learn to write, and to develop a style of their own. He recalls a certain Paul im Thurn whose distinctive italic style impressed him at university, and how he developed “violent downward verticals.” He writes of adolescent experimenters who amended their penmanship “sometimes as a response to an impressive master at school, sometimes independently, in their spare time at their desk in their bedroom, just wanting to be as elegant as possible.”

The Missing Ink has an amusing chapter on handwriting analysis—that bogus pastime—and is full of interesting observations and arcana. Hensher notes in his introduction that he cannot recognize the penmanship of his closest friends; never having seen their handwriting in the wild, he simply doesn’t know what it looks like. It’s a startling truth about modern life: I asked 15 colleagues, many of whom I’ve worked with for years, to put the sentence “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” on paper, and I was able to match only two of the samples to their owners. (Hensher also reveals that the British have many more interesting pangrams—or sentences featuring every letter of the alphabet—than we do, among them: “Waltz, bad nymph, for quick jigs vex!,” “Amazingly few discotheques provide jukeboxes,” and “TV quiz jock, Mr Ph.D., bags few lynx.”)

But what Hensher’s book continually emphasizes is how brief and ill-starred the history of handwriting has been. Although a fuller account is available in Kitty Burns Florey’s Script & Scribble (and if you’re thinking of buying a book of handwriting nostalgia this holiday season for the pen freak in your life, Florey’s is the one to get—it’s just as charming and much more informative, full of usefully placed examples and illustrations), Hensher gets the basics down. Before the industrial revolution, handwriting was the province of the elite; with the rise in the 19th century of commerce and clerks and an office-inhabiting worker class came schools of penmanship designed to “get things done neatly, get them done quickly, and get things done correctly.” The first of these, Spencerian copperplate, was modeled on engraving and was thought—like so many things during that period—to engender moral uplift. It did so, per its proponents, by leading the untoward and unwashed to contemplate pleasing forms “such as a nice rounded o.” (“If I were a Victorian urchin,” Hensher notes, such sentiments “would persuade me to stay in the gin shop for the rest of my life, making rude marks on the billiard board with a crayon clutched in my fist.”)

After copperplate came a few other schools, notably Vere Foster’s “civil service hand” in the United Kingdom, and Palmer cursive in the United States. The Palmer method, which is almost certainly responsible for the way your grandmother wrote on your birthday cards, seems today to be full of superfluous curlicues, but it was actually designed, we learn, with speed and physicality in mind. A.N. Palmer, its progenitor, was an advocate of “whole arm movement”—a way of creating letterforms from your shoulder, rather than just the hand and wrist—which he thought helped people write with greater speed for longer periods, without cramping up.

Although these historical tidbits are fascinating—the chapter on the absurdly indecipherable script prevalent in Germany before Hitler banned it helps demonstrate how arbitrary and cultural our writing conventions are—they have one point in common. Every innovation in handwriting was designed to improve the speed and legibility of human communication. And here is where Hensher’s quixotic defense of the hand stumbles. For what is faster and clearer than typing? Weren’t you slightly relieved when the handwritten paragraphs in this review came to an end, leaving you on the sturdy shores of a new thought expressed in Microsoft Verdana? Isn’t it easier to catch my meaning, to pay attention, when you are staring at a nice clean block of type?

Author Philip Hensher.

Eamonn McCabeI once wrote a story about the value of hand-drawn maps, which, like handwriting, are endangered by technology. Why draw your pal a route to the library when he can just look it up on his phone? Cartographers argue, however, that hand-drawn maps are often much more sophisticated than computer generated ones, which fail to organize the information they contain in any useful way. A hand-drawn map can compress the scale of uneventful portions of the trip (drive 400 miles on I-95) and zoom in on tricky ones (here’s how to avoid that toll in Delaware) in ways that computers are just learning to mimic.

I am not sure, though, that there’s a similar case to be made for the utility of handwriting. It is simply not the clearest way to communicate if expressing what you mean swiftly, and being understood, is your primary purpose.

Which means the only case for handwriting, at this point, is the nostalgic one—and it is not without merit. There remains something wonderful about receiving a letter that has been physically touched—actually crafted—by the hands of your correspondent. Perhaps the same people who sell handmade whatsits on Etsy as crocheted rebukes to the digital age will soon take up calligraphy en masse—and more power to them. I will certainly keep sending hand-written notes from time to time. But let’s face it: Cultivating fine handwriting is now an indulgence, a hobby for the aesthetically minded, like knitting, or decoupage. Our children must learn to write in school—but they probably don’t need to write that well.

Hensher concludes his book with a plea to keep handwriting alive: “To continue to diminish the place of the handwritten in our lives,” he writes, “is to diminish, in a small but real way, our humanity.” But in a world where typing is dominant, perhaps our humanity will be even more apparent: We’ll be judged not by our dexterity with a UniBall, but by the things we choose to say.

—

The Missing Ink by Philip Hensher. Faber and Faber.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.