Plato didn’t ban poets from his ideal city because they were wrong. He banned them because they were persuasively wrong: interested in appearances, trained in enchantment—just the kind of people to convince you that life in a cave was grand. As the Milwaukee poet John Koethe observes in his latest collection, ROTC Kills, TV and movies have taken over the role poetry once had in our cultural imagination. Now out at the margins, poetry more often trains its attention on our illusions, looking to disrupt, critique, and map our mistakes rather than build new myths. If that seems like a good reason to go to the movies, it’s also a useful role for an art form that can’t compete with masscult on its own terms.

For Koethe, the main illusion is also the indispensable one: The feeling that life has a purpose. A long-time professor of philosophy, now retired (“from what?” a friend jokes), Koethe, now 67, remains a remarkably gentle poet—one whose meditations never mystify, even as they take in Plato, Wittgenstein, Berkeley, Aristotle, and a host of contemporary philosophers most of us have never heard of (not to mention other poets, a couple of novels and, appropriately enough, plenty of movies). Koethe’s poems drift from memory to reflection and back again, taking on an almost tidal quality as they describe the mind’s motion into and back out of a sense of rightness. Writing in long, mostly iambic lines, usually five beats or more, he creates an accommodating ease:

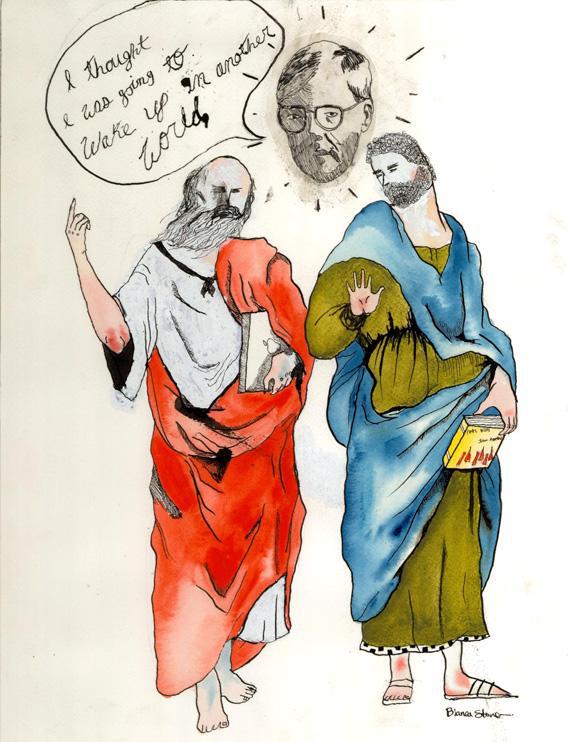

I thought I was going to wake up in another world,

And so I have, but it’s the one where I began. The sunlight

Just came back, as what begins in gladness and uncertainty matures

Into a kind of baffled happiness, unfinished and complete.

I have the sense of something constantly receding, the way

The future does, then suddenly returning, like the past.

It’s all so confusing, and yet it doesn’t bother me—

Everything evaporates, but some of it eventually comes back

In the uncertain form it assumed in the first place—

A remnant still intact and seemingly as distant from me

As the books in the library I keep remembering and looking up,

And as close as them too. But I loved it, whatever it was.

Here, as in so much of his work, Koethe sounds like his idol John Ashbery, but where Ashbery’s grand, wistful visions are always dissolving at the edge of sense, Koethe values clarity even when confronting a world that only seems to be clear, as when he writes of his parents: “They’re both dead now,/ And all I have to wrestle with are words, and yet these/ Syllables bring back the feeling of those summer afternoons.”

That said, ROTC Kills can be a baffling book, in which acceptance can border on indifference and memory can be its own justification. It’s hard to tell what he’s up to, even though the poems are full of self-awareness, including multiple references to other poems in the book. He repeatedly talks about how close death is, but rather than looking into the abyss he seems to be resigning from life, an impression that is deepened by his commentary on contemporary politics and society—observations that, while not necessarily wrong, seem calcified and incurious (“The silence in what people used to call the streets/ Is deafening, all talk is on the radio. …”) Meanwhile, Koethe has scattered the book with poems made up mostly of reminiscence, and without the buttressing skepticism that makes the past so powerful in his best work. Though these poems can be frustrating, they also heighten the stakes for Koethe’s longstanding interest in the persistence not only of the past but of the future that past promised us, partly by demonstrating the consequences of staying too attached to an old idea.

The book offers plenty of writing that shows just how agile Koethe still can be when he unleashes his imagination. He is a beautiful writer, one whose subtle inventiveness can give new life to persistent images (“the steep, unglaciated hills …”), nail a complex feeling in just a few words (“the ghostly consolations of the past”), or make the basic tools of the poetic trade into sources of pleasure and persuasion. Note the line break in this couplet from the collection’s title poem, about radical posters from the ‘60s that he still keeps on his walls:

I realize they’re footnotes, surface irritants that left the underlying

Language undisturbed.

Photo by Evin J. Miyazaki.

That small interruption gives the phrase “Language undisturbed” a remarkable, restorative power.

As Stephen Burt has written, poetry demands time out from much of what we think of as life. At times, reading ROTC Kills, I worry that Koethe has been too successful in eluding the demands of life. These poems are unusually short on references to living people—people who bring obligations—and some vitality disappears with them.

In a characteristic moment, he observes, “The elegance/ Is always in the telling, not in the truth, and yet/ Sometimes the words still speak to me/ As if they were true.” Where that “as if” pulls most strongly, our illusions matter most, and Koethe’s ability to enact the ways we can live meaningfully, beautifully, and uncertainly in that place make him a uniquely inspiring artist. I wish him more of the life that takes him there.

—

ROTC Kills by John Koethe. Harper Perennial.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.