What Midwestern childhood spent bellied up in front of the family TV set wasn’t shaped in some small but inexorable way by the Empire Carpet Man, that folksy spokesman who always managed to slip you his number before you flipped the channel? The disarming riff that teed up the “588-2300” jingle was so crucial, the copywriter, Elmer Lynn Hauldren, donned the denim himself and proceeded to invade our living rooms for the next 20 years, even if we never bought a yard.

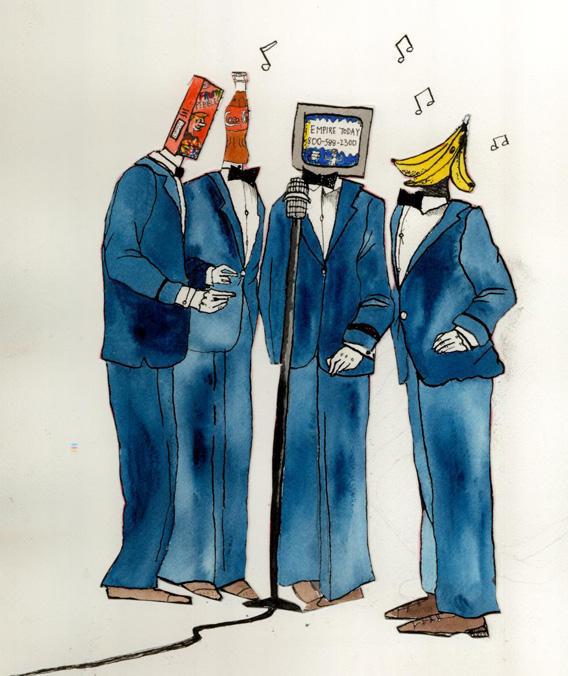

Could Kraftwerk have made a jumble of numbers any catchier than that jingle, performed by Hauldren’s own barbershop quartet, the Fabulous 40s? And why was I protective of those manipulative notes? I still remember the shock when I heard the song in New York with “800” shoehorned at the top of the harmonized call signal, a mandatory addition once the company expanded beyond Illinois. That was my carpet jingle!

How is it that I was forced into associating the uninvited Fabulous 40s with a sense of home? And likewise, why, to this day, when I hear the chorus of the Four Tops’ classic “I Can’t Help Myself,” does an unwanted internal vocalist always sully the payoff with, “It’s Duncan Hines and nobody else”?

This question—how the Motown Sound was co-opted to hype cake frosting—is tackled in a particularly fascinating section of Timothy D. Taylor’s absorbing new book, The Sounds of Capitalism. Having guided the reader through some of the most successful jingles of the radio and television era—from the wholesome days of ditties by the Wheaties Quartet to the full-scale invasion of earworms written by the Madison Avenue Choir—Taylor arrives at the “parody fever” of the early ‘80s in a chapter appropriately titled “Consumption, Corporatization, and Youth.” Though well-known phrases, melodies and song lyrics had been re-recorded and customized for commercial recordings for decades, Taylor writes that executives pounced when a certain heartstring was tugged by the boozy, sing-along nostalgia captured in 1983’s The Big Chill. The first company to tap this new vein was Ford, which crammed 17 oldies into one TV spot. Sizing up his Baby Boomer targets, a creative director involved in the campaign said, “[The music] recalls their adolescence, the most exciting time of their life, and it transfers some of those good feelings to Lincoln-Mercury.”

The unexpected effect, of course, was that kids of the ‘80s, like me, never had a chance to experience Motown before Madison Avenue introduced us to its parodies. We just thought the California Raisins knew how to move a crowd. This is not to suggest that such a practice was exclusive to the ‘80s. I doubt the kids of today, for example, will be able to slow-dance to Sarah McLachlan’s “Angel” without crying into their corsages, images of exploited animals now haunting the dance floor.

Though it’s easy to be cynical about the swindles examined in The Sounds of Capitalism—the closing chapters on gray-flannel advertisers going hip provide plenty of ammo—there is actually much to admire, or at least concede, about the industry’s triumphs. Perhaps the greatest attribute of Taylor’s exhaustive research is that it awakens the reader to the ingenuity of jingle writers, especially in the frontier days of radio. Tracing their patterns of speech and melody to distant precursors like the “verse without music” that peppered print advertising in the Victorian era and the sung advertisements of wandering street merchants, Taylor shows that jingle writers of the 20th century managed to create a new, potent language of their own. As far back as 1896, a book on advertising noted, “It is astonishing how some of the things we think the silliest will stick in our minds for years.”

It’s also astonishing to discover how much restraint programmers exhibited at the dawn of the radio age. Fearful that overt pitches might sour new listeners, promoters favored “indirect advertising” to keep the medium afloat. Warnings like “the family circle is not a public place” and “the announcer is an invited guest” echoed across magazine editorials. The most effective way for advertisers to generate goodwill was to provide music programming, which dominated the airwaves in the ‘20s. Announcements and ads were carefully woven into the shows, to minimize intrusion. Behind the scenes, however, advertisers were maniacal about securing their target demographics. The choice of music was endlessly debated and test-marketed. Researchers went door-to-door to thousands of homes to pinpoint preferences. Pollsters wanted to know: Pipe organ or Hawaiian? Ultimately, the consensus was jazz—or, as Taylor more accurately defines it, “highly arranged quasi-classical dance tunes performed by white musicians.”

Listeners ate it up. By the early ‘30s, newspapers were running profiles on not just band leaders but the production men and control engineers who made the programs possible. As the decade drew to a close, producers feared that music was becoming too familiar and might fade into background noise, so they pursued radio personalities who packed maximum punch. Though this was a far cry from the shock jocks of today, the foundation had certainly been laid.

During the Great Depression, there was a “near total blackout on discussions of current problems on the radio.” Comedy shows reigned. To stretch the dollar, advertisers demanded more effective ads, resorting to “carnivalesque tactics.” I couldn’t shake the feeling that the analog pleasures of early radio would cure some of the ailments fueling our current Great Recession. The fan letters that poured into radio stations kept the USPS plump. Trade publications kept printing presses humming. Musicians and workers were unionized. Advertisers could rely on a built-in audience that couldn’t fast-forward commercials.

One commercial that couldn’t be avoided, even by those who didn’t own radios, was the “Pepsi-Cola Hits the Spot” campaign of 1939. Arguably the first jingle to go viral, long before the company torched Michael Jackson, the tune achieved saturation not just over the airwaves; more than a million phonograph records were pressed for distribution in jukeboxes across the country. Kids everywhere sang it at home, at no charge to the advertiser (and “with the added benefit,” Taylor writes, quoting a Nation article, that children “are also much more difficult to turn off”). At the Pepsi headquarters in Long Island, the proud boss even installed a set of electronic chimes on top of the plant to play the first seven notes of the jingle every half hour. (I suppose that generation of workers didn’t have much of a choice.)

The next jingle to hit it big was the 1946 Chiquita Banana spot that made Americans crazy for calypso. Reading the lyrics, I couldn’t help but wonder if that famous opening hook—“I’m Chiquita Banana and I’ve come to say, I offer good nutrition in a simple way”—wasn’t the kernel of the corny trope in which any out-of-touch jokester could rap that they were “here to say” they liked something in a “major way.” The folks at Fruity Pebbles, for one, leaned pretty hard on it.

Indeed, when rap broke through in the ‘80s, advertisers were at the ready. “Part of the appeal seems to have been that a good deal of information could be imparted by rapping the lyrics,” Taylor writes. Russell Simmons notes that the use of hip-hop in commercials wasn’t selling out, because “being a starving artist is not that cool in the ghetto.” By the time Run-DMC nabbed a sportswear line after releasing “My Adidas” in 1987, Adidas had already been slipping them shoes for years.

As memorable as “My Adidas” was, my favorite moment of brand loyalty from DMC remains his ferocious shout-out to Ronald McDonald in “Son of Byford.” And while McDonald’s is responsible for their fair share of tongue twisters (remember the “Menu Song” pressed on flexi discs?) the fact remains that jingle writers of the ‘40s were crafting rhymes with more complexity than most of today’s club hits. And taking this one step further, is it possible that jingle writers predated beat boxing? Taylor recounts a labor dispute between recording artists and record companies in 1942 that led to oddball instruments not recognized by the union like kazoos, Jews’ harps, and musical saws being used for the recording of TV jingles. Most strikingly, singers also mimicked full bands with their mouths. Said adman Robert Foreman: “Some of our people can dub in a bass fiddle by blowing a ‘puck-puck-puck’ sound close to the mic. There’s one guy who does the snare drum, trumpet, and sax by breathing through his nose. He must be making a small fortune out of TV sound tracks.”

It is innovations and improvisations like this that make for such immersive reading in the first half of Sounds of Capitalism. And though Taylor does a fine job completing the circle, there’s simply not as much material to grapple with once music licensing became the name of the game in the ‘90s and beyond. Taylor astutely targets the “conquest of cool” phenomenon and chronicles the erosion of the sell-out stigma, explaining, for example, how the once-untouchable Beatles catalog has since become commercial wallpaper, with the controversial appropriation of “Revolution” in a 1987 ad for Nike serving as Trojan horse. I also liked being reminded of the day we all rushed to snap up that Nick Drake song from the Volkswagen commercial, pretending we’d owned it all along. But it’s less fun to read about Moby’s grandma-friendly techno and the millions of dollars it reaped in licensing than it is to discover a scrappy character like the banjo player Harry Reser, who created “sparkling” music for the Clicquot Club Eskimos radio show in 1929, which in turn made listeners think of sparkling ginger ale.

I guess I simply appreciate the spirit of jingle writers, even when their creations drive me nuts. The cannibalization of the pop charts and an endless parade of kitsch may be eroding the craftsmanship that made jingles such an experimental enterprise in the last century, but the practice is far from extinct. As any Chicagoan can attest, carpeting-related earworms didn’t end with Empire, especially considering Luna, another local carpet company, has already claimed the crown of catchiest jingle in the city. In New York, the “Hatfield and McCoy-style advertising war” between Dial 7 and their rival, Carmel Car and Limousine Service, whose jingle is a little too 6-centric for Dial 7’s taste, rages on. And don’t look now, but even the Free Credit Score band is back.

—

The Sounds of Capitalism: Advertising, Music, and the Conquest of Culture by Timothy D. Taylor. University of Chicago Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.