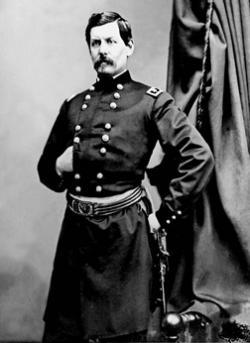

Imagine, for a moment, that it is 1862 and you are Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, the Union’s premier fighting force. The Confederate Army, led by Robert E. Lee, has just invaded Maryland. As you’re preparing your strategy for checking Lee’s advance, a message arrives at headquarters: A corporal from Indiana has found an envelope lying in a field near enemy lines. Inside are three cigars. Oh, and a copy of Lee’s Special Order No. 191, detailing his invasion plan and revealing that the Confederate general has split his force in two, a daring move that has left his army dangerously exposed to attack. You’re George McClellan—beloved by your soldiers, tasked by your commander-in-chief with destroying Lee’s army. What do you do?

Smoke the cigars, obviously . But after that? If you answered, Attack with all possible speed, by god!, you have a lot to learn from Richard Slotkin’s The Long Road to Antietam: How the Civil War Became a Revolution. As its title suggests, the book sets out to show how the nature of the war changed during Lee’s Maryland campaign, which culminated in the famously bloody Battle of Antietam. Up until that point in the war, powerful men on both sides of the conflict believed that a negotiated peace might be hammered out. But after 3,600 Americans died fighting outside a farming village on the banks of Antietam Creek, Lincoln would issue the Emancipation Proclamation, a radical document that ended any hope of reconciliation. In the wake of Antietam, the Union would fight an all-out war of subjugation, with the goal of crushing the rebellion beneath its Yankee boot and ending the institution of slavery by force.

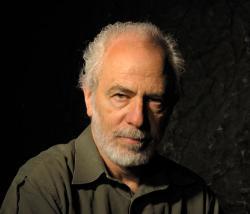

Slotkin, a historian and a writer of historical fiction, offers an absorbing account of this evolution. But the central figure of The Long Road to Antietam isn’t the author of the Emancipation Proclamation; it’s a man who openly opposed it—George McClellan. Vainglorious but insecure, power-hungry but risk-averse, a Democrat fighting a Republican’s war, McClellan is arguably the Civil War’s most fascinating figure and certainly its most frustrating. In McClellan, Slotkin finds an embodiment of the thinking that Lincoln repudiated with the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, namely the idea that the South should be compelled to rejoin the Union, but allowed to preserve its peculiar institution. Unfortunately for Lincoln, McClellan was also the Union’s best hope for delivering a battlefield victory big enough to give the president the political capital required to issue such a controversial proclamation. Reading deeply and thoughtfully through McClellan’s correspondence—the general didn’t so much as trim his moustache without first dropping a line to his wife Mary Ellen—Slotkin paints a detailed portrait of the talented but flawed general who helped Lincoln bring about his revolution, if ever so unwillingly.

So what did McClellan do when presented with the copy of Lee’s invasion plan rolled up with those cigars? He first sent a few telegraphs to his superiors crowing about how he was about to deliver a decisive victory. (To Lincoln: “I have all the plans of the Rebels and will catch them in their own trap.”) But he soon fell victim to the second thoughts that plagued him throughout his career as a commander. Though he issued orders to act on the intelligence, they exhibited, in Slotkin’s words, a “balance between boldness and anxiety,” and failed to take full advantage of his remarkable good fortune in stumbling upon his enemy’s plan. (As Slotkin notes, the discovery of Lee’s orders was pure serendipity—intelligence-gathering was among McClellan’s weaknesses.) Union forces won a minor victory on the strength of the lost plans, at the Battle of South Mountain, but failed to destroy Lee’s force, allowing him to retreat and fight another day (at Antietam, it would turn out). Despite the modesty of the South Mountain victory, McClellan reported it to his wife with typical immodesty: “If I can believe one tenth of what is reported, God has seldom given an army a greater victory than this.”

Here, as throughout the book, Slotkin is careful not to use the benefit of hindsight to judge McClellan too harshly. He isn’t convinced, as some of the general’s tougher critics have been, that had McClellan acted without anxiety his army could have decimated Lee’s at South Mountain. “It could be argued,” he writes, “that McClellan’s caution was reasonable given his estimate of enemy strength, even if it is hard for historians who know how wrong McClellan was to accept that judgment.” Partially as a result of his poor intelligence-gathering apparatus, McClellan had a tendency to wildly overestimate the size of his opponent’s army and thus miss opportunities to exploit his superior forces. At Antietam, McClellan would convince himself that he was facing down a Confederate force of 65,000 men. Slotkin figures the number was more like 36,000.

Though McClellan often seemed to be afraid of his own shadow , he could also be wildly self-assured, and The Road to Antietam captures him in all of his megalomaniacal glory. (McClellan’s nickname was “Young Napoleon,” but reading Slotkin’s book I imagined him as an unholy combination of Alvy Singer and Douglas MacArthur.) “He would come to see his elevation as providential,” writes Slotkin, “and would interpret his successes and failures as signals of God’s intentions toward the American republic. … He confided to Mary Ellen his sense that ‘by some strange operation of magic I seem to have become the power of the land.’ ” It’s self-regard so grandiose it verges on treason.

McClellan believed that he, and he alone, could save the nation from ruin—both the ruin threatened by Bobby Lee’s army and the ruin threatened by those in the Republican Party who would abolish slavery. “McClellan was living in a military and political fantasy world,” Slotkin writes, “in which he was the central figure in a two-front war to save the Union from the Rebels in front and the Radicals in the rear.” But rather than spur him to action, the fantasy only reinforced his trepidation. McClellan was loath to commit his troops to battle, Slotkin argues, for fear that a loss would give his political enemies the ammunition they needed to relieve him of his command.

He certainly wasn’t going to risk his neck to help a rival. To show us McClellan at his self-serving worst, Slotkin takes us back to the Second Battle of Bull Run, in August 1862, in which Robert E. Lee badly outmaneuvered a Union force commanded by John Pope. The North had forces that could have come to Pope’s rescue, but unfortunately for the soldiers being cut down by the Confederates, those forces were commanded by McClellan, who saw Pope as a threat to his ambitions. Despite repeated orders to reinforce Pope, McClellan dragged his feet, asking for clarification on who would be in command when he arrived on the scene. By the time he got his troops to the field, it was too late. Slotkin quotes Attorney General Edward Bates’ assessment of McClellan’s performance: “a criminal tardiness, a fatuous apathy, a captious, bickering rivalry, among our commanders who seem so taken up with their quick-made dignity that they overlook the lives of their people & the necessities of their country.”

Photo by Bill Burkhardt.

Why on earth would Lincoln suffer such insubordination? For one, there was a paucity of Union generals with command experience at the outset of the conflict. To paraphrase a confounding military mind from our own era, you go to war with the generals you have. The Union war effort also relied on a fragile coalition of Republicans and so-called War Democrats, who would have blanched at McClellan’s ouster. (McClellan was well-connected in the party, and would unsuccessfully challenge Lincoln as the Democratic nominee in the 1864 presidential election.) And finally, despite his failings, McClellan’s men loved him — as any soldier might love a general disinclined to risk his men’s lives.

The Long Road to Antietam culminates in a detailed account of the titular battle, in which McClellan finally committed his troops to an all-out engagement. The blow-by-blow description of the fighting may tax the patience of the lay reader; what goes by in a matter of pages in a popular survey like James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom here occupies several chapters overflowing with carnage. (Twenty-five thousand soldiers were killed or wounded on Sept. 17, 1862, making it arguably the bloodiest day in American history.) But Slotkin’s description of the battle is essential to completing his meticulous, maddening portrait of McClellan. Though he commanded a superior force—and though he drew up a sensible strategy for vanquishing Lee’s overtaxed army—a tentative McClellan nearly snatched defeat from the jaws of victory, ultimately allowing Lee to retreat back to Virginia with his army badly bruised but intact.

Unluckily for McClellan, his victory at Antietam was just decisive enough to give Lincoln the political cover he needed to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and set the war on the president’s new, revolutionary course. The victory was also just limited enough to give Lincoln the political cover he needed to issue Young Napoleon a pink slip and put the Army of the Potomac in the hands of men committed to stamping out the rebellion and the insidious institution it sought to safeguard. McClellan had finally gone to battle, and won, but the victory proved to be his undoing, not the coronation he’d imagined in his letters to his wife. Close, but no cigar.

—

The Long Road to Antietam: How the Civil War Became a Revolution by Richard Slotkin. Liveright Publishing.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.