As prophetic an instrument as it can be, the novel is rarely predictive, in a straightforward, short-range, weather-forecast sense. The oracular nightmare (1984), the visionary comedy (Yellow Dog)—these tend to fulfill themselves in the imagination, not in actuality. To this broad rule Raymond Kennedy’s Ride a Cockhorse, first published in 1991 and recently reissued by New York Review Books, is a fantastic, florid exception. So completely, in fact, did this work of fiction anticipate the real-life rise of a certain Alaskan politician/celebrity, that were it written today, after the event so to speak, we might read it as a rather ponderous and literal-minded allegory.

Of course I’m overstating the case here, like a good journalist. For one thing, Raymond Kennedy, as a writer, was incapable of ponderousness. And the character and progress of Mrs. Frances “Frankie” Fitzgibbons—volcanically sexed-up heroine of Ride a Cockhorse—do not map with total precision onto Sarah Palin, her career, exploits, et cetera. Nonetheless, Kennedy’s book does exhibit among its other qualities a quite freakish degree of prescience and diagnostic foresight—such that it might even, who knows, help us understand the whole Palin “thing.” So in the name of the Republic, let’s have a look at it.

To summarize the plot rather crudely: Frankie Fitzgibbons is a demure and docile small-town New Englander, 45 years old, not long widowed, who one day goes bananas and begins to take over the world. I say “goes bananas,” but the first symptom of her disorder is a kind of bewildering (to others) supersanity: a fierce eloquence, a white-hot clarity of mind. It comes upon her suddenly, Pentecostally almost, while—in the course of her duties as home loan officer for the Parish Bank—she is on the phone with a woman who has been falling behind in her mortgage payments. “If you’re looking for a sympathetic ear,” snaps Mrs. Fitzgibbons, hitherto a reliable provider of just that, “you’re barking up the wrong tree.” Her new voice rings out, loud and muscular with cliché, turning heads, taking no crap. She has been reborn. “Remarkable as it might seem, with that one line, Mrs. Fitzgibbons put behind her years of futile, soft-soaping diplomacy.”

Ride a Cockhorse by Raymond Kennedy.

And so begins her reign of terror. Mrs. Fitzgibbons increases in confidence. She increases in personal magnetism. Out of nowhere she has a violently expansive corporate agenda. The slow-moving men in her way, the comfy old chauvinists, must be overwhelmed. She orders people about, amazes them. She initiates a wave of firings—some random, some vindictively personal. She makes enemies. She gathers acolytes. She becomes CEO of the Parish Bank, and in an interview with the local paper she lashingly disparages the bank’s competitors (“… local-yokel-operators … I’m not going around them, I’m going to roll over them.”) The press eats her up: “Woman With A Will!,” “Fitzgibbons Throws Down Gauntlet!” She appears on television, ranting, despotic with charm. Her libido is enlarged, and she takes a young lover. And each morning, before she goes into battle, she is adoringly beautified by a hairdresser named Bruce.

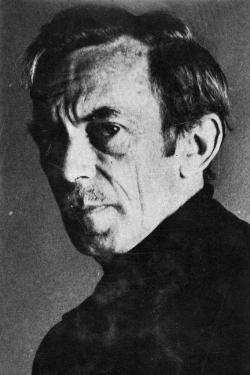

It all ends in tears, as it must. Flaming, cometary, out of her mind, Mrs. Fitzgibbons loses control and is dragged to earth at last. Opinion is divided—by which I mean, my opinion is divided—as to whether Raymond Kennedy himself loses control at the end of his book. A patrician New Englander, superbly lugubrious in aspect, Kennedy taught creative writing at Columbia and died in 2008. Ride a Cockhorse was his sixth novel, and his maddest. What Mrs. Fitzgibbons does to Louis Zabac, diminutive and well-groomed chairman of the Parish Bank, on the stairs of his own house … Over this grotesque episode we shall draw a veil.

Courtesy Branwynne Kennedy.

Then the shining hour, the dazzling hour, at the Republican National Convention in 2008, when Palin took the podium in an ecstasy of Fitzgibbon-ness, her face hard and beautiful, her $2,500 dollar Valentino jacket immaculately tailored, her backcombed updo crested and tailed like the helmet of King Leonidas—and all this before she even opened her mouth. “Sarah!” chanted the delegates. The job was already done: She could have waved in acknowledgement and stepped down. But she didn’t. She gave that sassy, bewitching, electrically scornful and paradigm-shifting speech.

The yin and the yang of Palinology are Going Rogue (by herself) and the scurrilous The Rogue (by Joe McGinniss): Palin as subject and object, the rock opera and the case history. It is the particular triumph of Kennedy’s style in Ride a Cockhorse to produce the impression that we are somehow, as it were, reading both books at once—that we are inside Mrs. Fitzgibbons’ head, sharing her exalted sense of significance and missionary urgency, while also observing her in near horror from the outside. In her case, dramatic as her achievements are, it comes down to ordinary madness: a common-or-garden manic episode. Sarah Palin, God bless her, is still out there, confounding the categories. No book has yet contained her.