Of all the animals you might choose to fight crime, a cat would seem the least promising. Cats, unlike dogs, are not ranged on the side of order against chaos. They are not motivated by simple human moralities, by universalized appeals to the superego such as “good cat” or “bad cat,” by guilt culture or shame culture. Instead they follow their own opaque behavioral structures: Toes are to be eaten but only in certain shoes, walls are to be attacked but only at certain times of day, humans are to be controlled through displays of affection or brute force depending on the hour and mood. Calling cats the “sociopaths of the pet world,” as Jonathan Franzen does in Freedom, rather misses the point. These are not pets in his condescending sense of the word; they are still half-wild creatures, domesticated at most 10,000 years ago— tens of thousands of years after the dog. And so expecting them to conform to human ethical codes is hopeless.

However, in one extremely popular section of the bookstore, cats don’t just conform to human codes, they actually enforce them. Cat mysteries, a subgenre of detective novels in which crimes are solved either by cats or through feline assistance, have been around for decades, selling millions upon millions of copies: Lilian Jackson Braun’s Cat Who… series began in 1966 and spanned 29 books before her death in 2011, while Rita Mae Brown just published the 20th in her Mrs. Murphy series, begun in 1990. Some cat mysteries, like the early Braun books and Shirley Rousseau Murphy’s more thoughtful Joe Grey series, are pleasurable reads; others significantly less so. But all impart some basic cognitive dissonance, given that every cat owner knows their animal is more likely to commit crimes than detect them. Given the extrasensory powers ladled out to felines in these books, my two cats would, I fear, waste little time in cementing their already Cromwellian sway over the affairs of my household.

So how to explain the continuing allure of cat mysteries? The long and twisted history of human-feline relations offers a few theories as to the origins of this unnatural chimera, the cat detective.

Cat Behavioralism. Cats are confounding creatures, and humans have long searched for ways to explain their habits. Christopher Smart’s 18th-century poem Jubilate Agno accounts for the daily movements of the poet’s cat Jeoffry with a ritual of prayer. (“For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way. / For is this done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.”) Similarly, the beauty of cat detective fiction is that it offers a compelling narrative for the strange things cats do. Your cat isn’t using your leg as a scratching post for no reason—he’s actually alerting you to a crime being committed right outside your door.

A common thread throughout cat detective fiction is the denseness of humans, unable to read subtle feline cues. In The Cat Who Could Read Backwards, the first Cat Who … book, the brilliant Siamese Koko adopts the far less acute newspaper reporter Jim Qwilleran, using familiar cat mind-control tricks to help Qwilleran solve the murder of Koko’s original owner: “Qwilleran grabbed the cat under the middle and carried him to his own apartment … but Koko was gone again in a white blur of speed, flying up the stairs and wailing desperately from the top.” When my cats do something like this, it’s generally unclear whether they want to eat, to play, or simply to move me arbitrarily from one room to another according to some strange chessboard logic. By the rules of cat mysteries, however, they are telling me there’s a dead body under the floorboards, and I am too humanly foolish to understand.

Cat Mythologizing. Because of the strangeness of cats, we’re likely to credit even paranormal origins to their behavior. Cats have for centuries been viewed as mystical creatures, associated with Egyptian death cults, Satan, and black magic, and have suffered through a number of unfortunate side-effects: In the Middle Ages, they were wrapped in swaddling clothes and roasted alive as Christian ritual sacrifices, whipped to death in English Shrovetide celebrations, and tried and hanged as witches. The literary history of mystical cats is extensive, from the witchly cat Grimalkin of the 16th-century anti-Catholic satire Beware the Cat, to Poe’s “Black Cat,” the demonic Behemoth in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, H.P. Lovecraft’s Cats of Ulthar, and Dr. Seuss’ Cat in the Hat.

Today, we read detective novels starring cats capable of human speech or shape-shifting, as in the Joe Grey books with their frequent references to Celtic Selkie myths; psychic reasoning and implausible acts of physical derring-do, as in the Braun books; or invisibility and teleportation, as with Sofie Kelly’s Magical Cats series. None of these abilities seems impossibly strange (or at least not as jarring as they would with a dog or a horse), given what we’re already used to from our cats—predicting death, for instance, or just walking diagonally in front of you when you’re trying to get to the bathroom. As one of the owners of the talking cats in the Joe Grey books says: “Cats’ strange habits and strange perceptions, that’s part of their charm. … Cats are admired for their peculiar behavior.” Cat detective fiction derives part of its pleasure from its expansive—but strangely believable—definition of “peculiar” cat behavior.

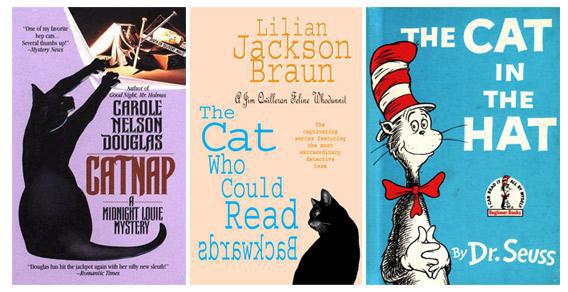

Catnap, a Midnight Louie Mystery; The Cat Who Could Read Backwards; The Cat in the Hat.

Forge Books; Headline Book Publishing; Random House.

Cat Power. The cat’s magical history connects it closely to women, and especially powerful and dangerous women. Associated with Egyptian goddesses Sekhmet and Bast, the cat was also a stand-in for the Greek goddess Diana, the Scandinavian goddess Freya, and for the Virgin Mary, according to a wonderful 1956 book called The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic by M. Oldfield Howey: “The darkness of the Virgin, and the black cat representing her [in early medieval art], is not the darkness of evil, but of the Uncreate, of the Great Deep, and the Unknown God.” The complexity of this image would prove too heavy for most medieval thinkers, who seized on the cat as a symbol of all that was unholy about women. Witch-hunting guides like the Malleus Maleficarum spread the idea of a cat “familiar,” and the woman living alone with her cats became encoded as a threatening figure.

Into this ugly history stride the mostly female heroines of the cat mystery genre (written exclusively by women). Jim Qwilleran aside, these are proud cat ladies. Most are single; if not, they are cozily long-married (like “Harry” Haristeen in the Rita Mae Brown books). Librarians abound; female friendship and feminine wisdom are celebrated. Patronesses of tea shops, bakers of bread, the women of cat mysteries commune with nature and prize herbal cures over Western medicine. In other words, they are classic witches, blessed with an extra reserve of mystico-feline power that allows them to solve crimes baffling the (mostly male) police. Even the sexier model in Carole Nelson Douglas’ Midnight Louie series, set in Las Vegas with a heavy emphasis on studly boyfriends and stiletto heels, follows the same basic pattern. “I make myself useful looking after her without letting her know about it,” explains Midnight Louie, animal familiar of amateur sleuth Temple Barr. Who could say no to that?

Cat Justice. In her book The Cat and the Human Imagination: Feline Images From Bast to Garfield, Katharine M. Rogers traces a literary connection between cats and justice: “The same silent movement and steady gaze that aroused suspicions of evil designs and ungodliness could be interpreted from a different point of view to give cats a role as accusing witnesses.” She cites Emile Zola’s François the cat watching Thérèse Raquin commit adultery in her husband’s bedroom: “Dignified and motionless, he stared with his round eyes at the two lovers, appearing to examine them carefully, never blinking, lost in a kind of devilish ecstasy.”

My cat Lucas has a habit of planting himself at eye-level on my desk and staring at me with what you might call devilish ecstasy until I get off the couch to feed him. He’s not inflicting righteous shame for my moral failings; he’s just bullying me. In the nostalgic small-town world of the cat-cozy, however, the cat’s unblinking eye often represents an uncorrupted, prelapsarian view of morality and justice. The transformation of Joe Grey from an everyday tomcat into a crime-busting cat-philosopher occurs when he witnesses a human killing in an alleyway and comes away horrified by its uncatlike barbarity: “Cats killed for food or to keep their skills honed. … Cats did not kill with the cold deliberation he had just witnessed.” The murky evils of the human world, as contrasted to the purer truths of the animal kingdom, make a constant refrain in the Rita Mae Brown books: “The animals, whose senses were much sharper, their minds not cluttered with ideologies that screened or blunted reality, often knew things before the humans did.”

Or, perhaps we just wish that they did—and in the universe of cat mysteries, we’re allowed to believe.

Cat Pee. Of course, the real reason people love cat mysteries could just be that the cats have infected our brains. Maybe we’re putting up with bad punning titles and storylines that revolve around cats trapping murderers in spiderwebs of yarn because of brain parasites. After all, what do scientists call the chemical attraction to cat urine shown to occur in toxoplasmosis-infested rats? “Fatal feline attraction,” of course.

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.