Springtime 1536, and in taverns and alehouses up and down England they are singing about Henry VIII’s sexual prowess: “the ballad of King Littleprick and his wife the witch.” That’s the national result of the rollicking affair that was at the center of Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel’s Booker prize-winning historical novel. In that work, Mantel dusted off Thomas Cromwell’s 500-year reputation as Henry’s sinister henchman, to bring a fresh character onto the world stage—a renaissance man who, as Wolf Hall informed us, is “at home in courtroom or waterfront, bishop’s palace or inn yard. He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury.” Only now he has 10 years of power behind him.

Mantel knows how to plunge the reader into the thick of things. At the end of Wolf Hall Henry VIII and his entourage were descending upon his latest romantic intrigue, Jane Seymour. Behind them were the machinations wrought by his chief minister Cromwell, ousting all who opposed the King’s separation from the Catholic Church. There was the sense of a great author at the height of her powers taking a breath and beaming; on the page, a palpable atmosphere of relief and future glory.

That atmosphere dissipates in the first few pages of Bring Up the Bodies, which picks up just two months later, as the court packs from a summer of hunts. Though this second book in a planned trilogy stands alone as a meticulously crafted novel, the first chapter is a seamless continuation of the final page of Wolf Hall; last seen galloping across summer fields, Cromwell returns watching hawks swoop in early autumn.

For the reader, there is a happy familiarity to a sequel. Even the two deaths that dominated Wolf Hall—beloved mentor Cardinal Wolsey, and sadistic fanatic Thomas More—hover ghostlike over Cromwell. He calls upon Wolsey for advice, and when he thinks of More, “He doesn’t exactly miss the man. It’s just that sometimes, he forgets he’s dead.” Death is everywhere in the book—Cromwell’s wife and daughters are ever remembered; the discarded Queen Catherine coughs her way to oblivion, forgotten in a country house; the jolly crew of sycophants around the king have no idea their demise is weeks away. Cromwell himself has less than five years before his own beheading.

Until then there is the magic of Cromwell’s mind. Cromwell: the blacksmith’s son from Putney, the soldier from Italian campaigns, risen to be the King’s right hand. Having more than ably established his humanity in Wolf Hall, here Mantel gives him free rein. You want to say that he is Machiavellian, but he’s already read The Prince and deemed it “almost trite … nothing in it but abstractions.”

One fool he suffers gladly is the king, who calls him “Crumb.” There are shades of Jeeves and Wooster, as the buffoon Henry, romantically hopeless, rages and whines and boasts, and the dark cloaked minister looks on gravely. Henry is made decent only by the reverence with which Cromwell treats him. But there is a limit. At one point, he screams at his chief minister: “I really believe, Cromwell, that you think you are king, and I am a blacksmith’s boy.” Cromwell reflects, “You could never be the blacksmith’s boy.” Mantel sets the stage through the autumn and winter before that deadly spring. The king grumbles frustrations, as the once-bewitching Anne turns shrewish, her womb not as promising as hoped. Anne is as haughty as ever, but after three years of marriage, she has gone from being so alluring as to inspire a new religion to annoying enough to provoke a beheading, all without changing her affect. Henry alights on wife No. 3, the plain Jane Seymour of Wolf Hall. It is up to Cromwell, once again, to intuit the king’s wishes and realize them. Only this time he doesn’t have eight years, just nine months. A procession of events: We’re at Christmas within 100 pages, then St. George’s Day and on into the breathtaking final third, the grinding death march.

This lends a sense of immediacy, as if after spending years honing Wolf Hall (and decades waiting for the opportunity) Mantel has to get the tale of Anne Boleyn’s downfall out of the way before the next volume. Bring Up the Bodies is still superb, but it is that much more breakneck, the intrigues hurtling forward.

This most shopworn of historical tales has been told in many ways, from the ponderously reverent (A Man for All Seasons) to the salaciously silly (The Tudors) and everywhere in between (see Philippa Gregory and Antonia Frasier). The most successful recent telling is C.J. Sansum’s terrific Matthew Shardlake series, the first two books of which feature Cromwell as the hero’s terrifying boss.

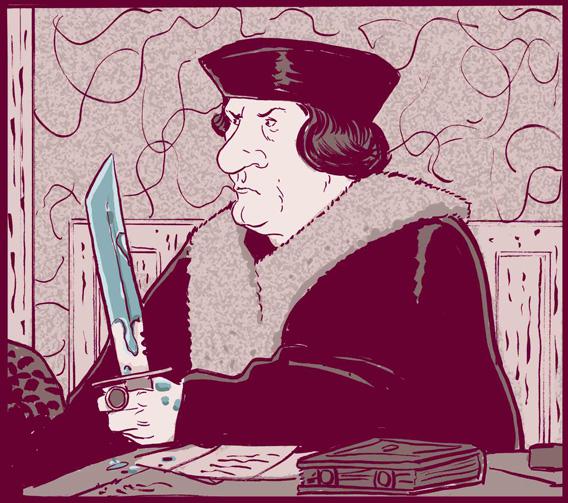

And of course there’s the Holbein portrait, a running gag in Wolf Hall, continued here as Cromwell mutters about being made to look like a murderer (Page 6). The portrait he refers to, now hanging at the Frick, makes him look like Tony Soprano: a fattened, middle-aged tough guy who can meekly bow and scrape to a lord a few months before having him executed.

Cromwell hasn’t just risen in the king’s court, he has been elevated in Mantel’s handling, so that the lowborn son whose coarseness so irked the lords is this novel’s guiding presence. This time around it is Cromwell’s humor, sensitivity, and reason set against the vulgarity of the dignitaries. It is a tidy sleight of hand.

Photograph by Jane Bown.

The level of detail in both books is so excessive that with a charmless narrator a reader would feel lectured. But Cromwell is exceptionally entertaining. Along with his grief, professionalism, and toughness is his sense of humor, Mantel’s sense of humor. Everything in the book is very funny, never more so than when Cromwell’s mind is turning a polite formal meeting into something so much darker.

Gruesomeness is blinked at with macabre glee. At a polite formal interview Cromwell notes of Anne’s doomed brother George: “Today he wears white velvet over red silk, scarlet rippling from each gash. He is reminded of a picture he saw once in the Low Countries, of a saint being flayed alive.” Mantel isn’t done yet: “The skin of the man’s calves was folded neatly over his ankles, like soft boots.”

As the noose tightens, and Cromwell focuses on the Queen, so does Mantel’s verve and wit, the courtliness giving way to ribald vulgarity, the queen’s womb a point of conjecture. Cromwell holds interviews with Anne’s ladies in waiting. “Who would not pass time with a man who has cakes?” he asks innocently of one pregnant lady. “You think I will confess just for cakes?” she asks. A few lines later: “That white one, is that almond cream?” Just as she spills the beans on her queen’s behavior. Cromwell is impassive, deadpan.

This is the greatest trick in the series and in this book, conveying the deep nonsense at the heart of courtly life, the upheaval of a nation over one man’s inability to produce a surviving male heir, or, for that matter, to deal with females like a man. Cromwell himself, less histrionic, has a one-night stand with an innkeeper’s wife.

Cromwell is still startled by his own survival. “He once thought it himself, that he might die of grief: for his wife, his daughters, his sisters, his father and master the cardinal. But the pulse, obdurate, keeps its rhythm.” That pulse is the careful, patient rage of the consummate professional in a world of highborn twits who never see him coming. At an interview with one of his victims, it dawns on the man that he is paying for his humiliation of Cromwell’s mentor. “Not one year’s grudge or two, but a fat extract from the book of grief, kept since the cardinal came down.”

You get the sense that he is grimly laughing at everyone, all the time, even as events become increasingly serious. His greatness is as inimitable as it is unfathomable to his contemporaries. Part of the story’s glory is surely its autobiographical nature, the notion that Mantel has here sublimated herself to Cromwell—the lowborn genius awash in grief rising above his contemporaries, astonished at the hypocrisy in society. One of the great satisfactions in watching Mantel win the Booker for Wolf Hall was her reaction to all the “oozing” of her contemporaries, who once reviled her, now congratulating her, much as Henry’s couriers compliment Cromwell.

This is a woman who said she “accumulated an anger that would rip a roof off.” Who endured decades of professional misogyny and medical misdiagnoses that altered her, body and mind. The clarity with which she finds Cromwell’s voice—halting in Wolf Hall—is here ragingly steady, a volcanic presage of what is to come. It is vindicating to see Mantel come into her own after 27 years and 10 novels, just as it is to see Cromwell in his element, still quiet and dark in the shadows, moving his betters around like pawns on a chessboard. The convincing revisionist history on display, that Cromwell executed four men on trumped-up charges for mocking Cardinal Wolsey after his death, is both tidy and chilling, making fierce sense of his resolute nature in the face of grief: “God takes out your heart of flesh,” he thinks, “and gives you a heart of stone.”

And yet for all the dazzle and momentum—the last hundred pages sail by—its sharply drawn vignettes, moments of beauty and hilarious vulgarities, there is the faintest comparative lack in Bring Up the Bodies. Set against Mantel’s singular achievement in Wolf Hall, this book feels not so much slight as a bridge to her next, a necessary and highly entertaining throat-clearing. Only a writer of Mantel’s abilities could be criticized for writing a merely brilliant novel, rather than another outright masterpiece. It is the scope that feels limited, the weeks in the novel as opposed to the years in the first. And perhaps that gnawing sense of consumerist pique that comes from knowing that even now, Mantel is writing about Cromwell’s fall from grace in the third part of this trilogy, The Mirror and the Light. That is the worst that can be said about Mantel—her latest book makes you angry, because you want more.

See all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.