by Rosecrans Baldwin

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Early in Rosecrans Baldwin’s droll and well-observed memoir Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down, Baldwin’s looking for an apartment in the Latin Quarter, and in the shadow of the Pantheon, he reflects on all that has happened since the days of Hemingway. He goes on to list some of these things: “Luke Skywalker had happened. Supermarkets happened. Hip-hop happened and Joan Didion happened. Email happened.”

Sans blague. The Paris of today is no longer your parents’ Paris, Midnight in Paris Paris—the city of Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and later Julia Child, of 20-franc hotel rooms and 5-franc bistro lunches. Paris has grown up, learned English, globalized, and gotten expensive. Meanwhile in America: Espresso has happened, Chez Panisse has happened, Napa Valley has happened. In both places, 1968 happened. Paris has sushi restaurants and immigration issues, and America has Whole Foods, which evokes such reverence in the French people in Baldwin’s book that they call it “unbelievable” and “so beautiful” and declare—crazily, to American ears—that “we have nothing like Whole Foods … show me where in Paris food is sold like art.”

So who is talking to whom here? Has America become more French, has France become more American? Baldwin, like many Americans, harbors fantasies about life in Paris—there he would discover his true artistic self, shed the banal skin of Americanness, and rediscover himself as a European. Perhaps he would learn to appreciate wine. He moves to Paris in 2007 to take a job as a copywriter for a big French advertising firm. He and his wife rent an apartment in the Marais, and when Baldwin isn’t writing copy, he’s studiously working on a novel, in another grand tradition of American writers.

It’s a little ballsy at this point to write an American-in-Paris memoir, given the genre’s deep bench. Since moving to Paris 18 months ago, I’ve read Hungry for Paris, The Sweet Life in Paris, Paris to the Moon, Lunch in Paris, and—most recently, after having a baby here myself—Bringing up Bébé. Every publishing season seems to bring its own Paris memoir, and every season I (and plenty of other Americans, in Paris or America,) snap these stories up. But what makes Baldwin’s book particularly enjoyable is that it engages with the clash of our American idea of Paris and Paris the modern reality. In Paris the global city, Baldwin continually runs up against his provincial and romantic fantasies, and then asks himself why he has them in the first place.

In many ways, Baldwin and I are in the same cohort: thirtysomething, college-educated, upper-middle-class Americans with jobs in media. We both moved to Paris from New York City with our spouses. Both of us first learned to revere Paris from our parents. Baldwin remembers visiting the city as a child and watching his mother transform into a woman over a bowl of café au lait. Similarly, I’m named after Éric Rohmer’s film Claire’s Knee, and my parents fed me escargot before I turned 10. Both of us were raised on the Paris of our parents’ expectations, a place where everything was a little more beautiful, more cultured, more intellectual, more delicious, more right.

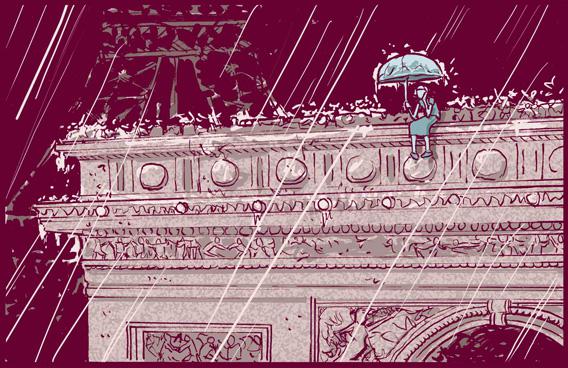

Against this shimmering ideal, modern Paris can be a bit of a slap in the face, sometimes feeling designed to sabotage all romance. The quaint bistro down the street from Baldwin is run by Australians, serves ostrich steak, and is wallpapered in pornographic cartoons. The Metro is crowded, the coffee is terrible, and it rains as much as in London. The most delicious and affordable food comes from the local frozen food retailer, Picard.

It may seem naive or even insane to cling to a romanticized image of a city when its full-blooded reality is staring you in the face. But Paris encourages such paradox because of how heavily it trades on its own romantic mythology. More international tourists visit Paris each year than any other city, and Paris knows what they come for: not just the Eiffel tower key chains but the quaint bistros, the sidewalk cafes, the Louvre, the croissants and the baguettes and the boules. Though a lot has happened since Hemingway, it’s still selling that story.

And it quickly becomes Baldwin’s job to sell it as well, because at his ad-agency job he writes copy for Louis Vuitton and other French brands. As one executive at a French brandy concern puts it, the agency’s chief dilemma is to “reconvince the world to love France” (p.196)— specifically, France the unquestioned authority on luxury, not only to Americans but to a larger world market, most notably China. Chinese nouveau riche are buying French liquor as a prestige brand, drinking cognac with their meals like wine. Despite gasps and exclamations of “But that’s not normal!” from the French people in the room, a market is a market, and if it’s the Chinese who now have the money to support the French luxury industry, then it’s China that France will market Frenchness to.

The most well-observed passages in Paris, I Love You come from Baldwin’s time in this very French office, where his colleagues eat their McDonald’s lunches in courses (McNuggets, then fries and a burger, then salad, then dessert), and he can never figure out when to kiss people on both cheeks. Here, cultural assumptions break both ways—while Baldwin seems fascinated by the sad, confident sexiness of most Parisian men, he’s also an object of fascination to many of his co-workers, who are dying to move to New York. One of the Web designers starts calling him “my nigger” until Baldwin tells him it cannot continue, and another takes him to lunch to furtively confess, in a Paris filled with indignant union workers constantly on strike, her secret capitalist leanings.

When Baldwin seeks his own idea of Paris, rather than focusing on that of his parents or on selling it to Chinese businessmen, he—and we—are often disappointed. Though he takes pains to explain that his neighborhood in the Haut Marais wasn’t yet hip in 2007, it’s still essentially Paris’ West Village, a picturesque quarter that feels like a small town, but where your neighbor just happens to be a millionaire film star. It’s where the cool globetrotting kids hang out, where you may hear more English spoken than French. The other expats he meets seem uniformly obnoxious, particularly those connected with A Small World, an invitation-only networking group that goes global with the cliquishness of high school. His descriptions of Small World parties—populated with trust-funders who exclaim “I don’t think I even know a Parisian, isn’t that appalling?”—made my teeth ache. Eventually he drops this group, tired of their rarefied bubble, but not before I’d heard way too much from them.

Baldwin is more interesting when he’s being a plain old immigrant and attending his Jour Civique (Civic Day), a course in French history and government required of all foreigners living in France. He’s the only American in a class populated by residents of former French colonies like Algeria and Senegal, and his fellow students fully grasp the irony of their former colonizer now instructing them on equality. In a lesson on laws about assault, the teacher asks the class if it’s legal for him to hit them; a young Tunisian replies, “I’m an Arab, so you probably can hit me. Maybe it depends where you hit me.” This Paris isn’t just a romantic luxurious dream, but part of a powerful country in its own right, with deep-seated problems of race and class that are different from our own.

Americans aren’t the only ones who go through profound Paris disillusionment; as Baldwin mentions in his book, there’s a psychological phenomenon called Paris Syndrome which strikes Japanese tourists when the reality of Paris doesn’t live up to the fantasy. As many as a dozen have to be repatriated each year when their disillusionment brings about nervous collapse. Even Parisians are sometimes happier thinking about Paris than living in it; one confesses to Baldwin, “I would not want to live here if I could choose a different history.” This sentiment is echoed by many of his coworkers, who feel trapped: Paris is far too expensive/crowded/elitist to live in, but it’s Paris—how could you leave?

Gradually, Baldwin’s fantasy Paris is replaced by reality, and he finds he loves that city, too. As in falling in love with a person, true love with a city only comes in accepting its faults, and for those of us who tough it out, the irritants of Paris can become badges of honor, and small triumphs. (In that way, it’s not unlike New York, the city celebrated and excoriated in the LCD Soundsystem song from which Baldwin pinches his title.) Baldwin finally knows he’s fluent in French when he can get the telemarketer from his mobile-phone company to stop calling him every day. I knew I’d make it here the day that, cut off by a monstrous Parisian scooter, I cursed in French. (Seriously, why drive a three-wheeled scooter with a windshield? Just buy a car already.)

There’s a weird kind of joy in figuring out how to get past, around, or through the bureaucracy, the paperwork, the endless dossiers and C’est pas possibles that make up life here as either immigrant or native son. It may not be the Paris of Miller or Hemingway, but it’s our Paris—where they review novels on the evening news, and where you can still buy a great bottle of wine for 10 euros and drink it on the banks of the Seine. Pas mal, non? Pas mal du tout.

Read all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.