This review is being published in partnership with Jezebel.com.

Illustration by Nick Pitarra

I don’t have any children yet, so my breasts are still more aesthetic than functional. I mostly use them as a food shelf, a cellphone case, and an in-flight pillow. When I was young and single and had less self-esteem, I used to joke that my breasts were “all I had” (good one, unhappy baby self!), but now that I’m older, I don’t have to rely on them to feel beautiful—for the time being, they’re just parts of me that fill my clothes and make my back hurt and, sure, make me feel pretty sometimes. I just don’t think about them that much anymore. Thanks to Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History, a surprisingly emotional book by Florence Williams, though, that’s all changing. All of a sudden I can’t stop thinking about my breasts. Because it turns out they are total jerks.

by Florence Williams

W.W. Norton

In Breasts, Williams, a contributing editor for Outside magazine, attempts to offer a comprehensive social, cultural, medical, and scientific history of the human breast, a la single-word-titled best-sellers like Cod or Salt or Stiff—though not, alas, Balls. (In an act of one-word-wonder solidarity, Stiff author Mary Roach blurbed Breasts, citing Williams’ “double-D talents.”) Though that genre of sweeping, single-topic histories can wind up feeling hasty and reductive (it’s hard to write the history of one thing without touching on the history of all other things), Williams’ writing is scientifically detailed yet warm and accessible. She also stays firmly away from the juvenile (BOOOOOOOOO!!!) and isn’t afraid to delve into her personal life, making Breasts a smart and relatable, if occasionally dry, read.

Williams’ journey begins when, alarmed by a news article about toxins in breast milk, she decides to get her own milk tested. And, surprise! It’s packed with toxins—specifically, chemical flame retardants—that Williams is funneling directly into her baby. (“Well, at least your breasts won’t spontaneously ignite!” her husband jokes, because that’s exactly what you want to hear when adjusting to the news that you’re a human baby-poison factory.) This sends her down a rabbit hole in search of deeper understanding of her own anatomy— into the evolutionary history of mammals, to Peru to investigate nursing and weaning, back to the first breast augmentation surgery, and all over the world to interview more boob experts than you can shake a pasty at.

And she discovers that breasts are complicated. Impossibly so. She learns that it’s the breast’s permeability that make it such an evolutionary powerhouse (lots and lots of estrogen receptors help human puberty occur at the optimal time; nutrient-rich breast milk makes for giant brains)—but that same permeability is also, partially, what causes one in eight women to develop breast cancer. Our breasts make us great but they also make us vulnerable, and you can’t help but come away from Williams’ book feeling a bit helpless. (Self-examinations! Self-examinations are key!) While she makes the story as dynamic as possible, there’s no escaping that this is science journalism—there are lots of PBDE levels and octa-203 and penta-47 and dioxin and “lobule type 4” and other such enemies of lively prose. But that’s OK—there are enough surprises and genuinely horrifying learning moments to keep a reader (especially a lady-reader), uh, latched on.

Five Things I Learned About Breasts From Florence Williams’ Breasts

1. Women: Your boobs are trying to murder you.

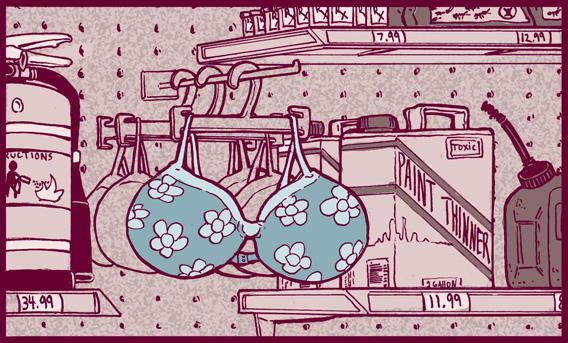

Right now. All the time. The day you were born, your boobs took one look at you and were like, “Oh, no. No. Absolutely not. Hey, does anyone know where I can get some poison?” Turns out, everywhere! Breasts are largely made up of fatty tissue, and chemicals looooooooooove to accumulate in fatty tissue. Here’s a partial list from Williams: “paint thinners, dry-cleaning fluids, wood preservatives, toilet deodorizers, cosmetic additives, gasoline by-products, rocket fuel, termite poisons, fungicides, and flame-retardants.” So what can you do to keep your chest-sponges safe from marauding chemicals? Nothing, pretty much, short of becoming a trillionaire and taking over literally every drug company and industry on earth. So get on it, concerned citizens! Step one: CoinStar.

2. Babies are cannibals and your breasts may be sexists.

A male baby requires almost 1,000 megajoules of energy in his first year of life. “That is the equivalent,” Williams writes, “of one thousand light trucks moving one hundred miles per hour.” And do you know where he gets all that energy? Not from the sun, unless you are a fern that somehow learned how to read the Internet (good job!). No, it’s from your boobs. HE’S EATING YOU. That little dude sucks it right out of you like the world’s chubbiest and least stealthy vampire. Which, of course, is exactly how it’s supposed to be—but it’s not surprising that so many women are leery of breast-feeding. On top of that, breasts (at least in rhesus macaque monkeys, whose milk is similar to humans) can actually determine whether a nursing baby is a boy or a girl, and adjust their milk production accordingly. Milk for girls is thin but abundant, while boy milk is fattier and scarcer—the theory being that girls then must stick closer to their mothers for frequent feedings, thus absorbing their social roles, while boys are easily sated and have time to play and explore. Um, way to prop up the patriarchy by reinforcing gender roles, monkey boobs.

3. Everything gives you breast cancer and nothing gives you breast cancer.

Williams learns about all the standard-issue risk factors for what is, by a wide margin, the most common life-threatening cancer among American women: age, family history, obesity, race, early puberty, late menopause. “But—and this is the disconcerting part—most people who get breast cancer have few of these risk factors, other than the big buckets of age and race,” she writes. Ninety percent of women with breast cancer have no known family history of the disease. Just as perplexingly, she notes, “most women with the risk factors, even a bunch of them, still never get breast cancer. In other words, the standard risk factors are fairly useless.”

Photograph by Corrynn Cochran.

So basically, if you want to find out your risk for breast cancer, you might as well just duct-tape a stethoscope and a mustache to a Magic 8 Ball and ask him. Don’t forget to flush $30 down the toilet for your copay.

4. Feel yourself up. All the time.

Breast cancer detection, according to Williams, “is as much art as science.” Every woman’s breast tissue is different—some have what are referred to as “denser” breasts, which might be firmer (an aesthetic boon by most standards) but make it more difficult for mammograms to detect abnormalities. And then there’s the issue that mammograms themselves, which use radiation, could actually be dangerous for women who are at the highest risk of breast cancer. (It might sound tempting to hypochondriacally forgo mammograms altogether, but I’d rather let a trustworthy doctor make those decisions.) Breast self-exams, or BSEs, Williams argues, are a vital detection tool—if we can educate women to actually perform them properly, instead of “half-assed shower gropings.”

Williams actually purchases a fake, cancer-ridden practice breast from Amazon.com—and works it over like some sort of tumor-ridden petting zoo (adorable!). But when it comes to her actual human breasts, she discovers, exploration isn’t so straightforward: “It was harder (and painful) to push down very far through all my natural ropy tissue. If I were to develop cancer, I’d have to hope for shallow tumors.” So, OK, it’s not as simple as “feel yourself up,” although the commitment to trying is a valuable step. But BSEs aren’t a pass/fail exam. You don’t get points just for showing up and cupping your boob for 30 seconds. You have to probe systematically and thoroughly for, according to Williams, seven minutes per breast if you want to be sure you’ve covered all the territory. This, obviously, is terrifying. I’m pretty sure I’ve never delved deeply enough into my own breast tissue to detect anything but the most shallow and superficial evils. As far as I know, there’s a fucking balrog down there.

5. Learning about breasts is a feminist action.

Breasts are sexualized, fetishized, criticized, ridiculed, obsessed over, augmented, flaunted, and stigmatized—but rarely are they taken seriously. It’s like we think about them constantly while simultaneously not thinking about them at all. I know it’s hard for people attracted to breasts to wrap their heads around the idea that they aren’t just fun, they’re also functional. It’s difficult to adjust to the idea that your favorite sexual organs are also reproductive organs. I get it. I know if a baby came out of a penis I’d think of penises way differently (also that baby would be hella gross). But eventually I’d get over it (maybe).

Breasts, writes Williams, need “a safer world more attuned to their vulnerabilities, and they need good listeners, not just good oglers.” Do you hear that, boob men of America? Ogling is not enough. If oglers want to keep on ogling, we’re all going to have to start caring more about women’s health. I worried a bit going into Breasts that all this feminist advocacy for women’s health might make breasts less sexy. (If there’s one thing I’ve learned from being an unapologetic loudmouthed feminist it’s that a lot of people do not like listening to unapologetic loudmouthed feminists.) But thanks to Williams’ indefatigable good humor and conversational candor, I’m inspired to believe that maybe sexy, sexy breasts can help make feminism more sexy! So come on, oglers. It’s time to pony up. Next dude who talks to my cleavage instead of my face will be expected to send 20 bucks to Planned Parenthood.

See all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.