The moment when the economy seems to be turning around is perhaps not the best time to publish a book explaining why it took so long to get things right. Still, with his new book, The Escape Artists: How Obama’s Team Fumbled the Recovery, Noam Scheiber offers a persuasive take on administration policymaking, one in which there are no heroes and no villains, no fools, no saints, not even a clear road not taken. It’s a portrait of a team that failed in its responsibility to the country to avoid a prolonged and cataclysmic downturn, but did so under extremely trying circumstances—and still, arguably, produced the best possible result.

by Noam Scheiber

Simon & Schuster

That nuanced view comes, unfortunately, at the expense of drama. Unlike Ron Suskind’s more sensationalistic Confidence Men, Scheiber’s tale doesn’t have a single storyline to propel you through its pages. Different issues are faced, different coalitions of advisers emerge, and different choices are made for different reasons. On fiscal stimulus, Lawrence Summers was consistently to the left of Tim Geithner. On the Dodd-Frank bank regulation bill, their positions wound up reversed. But much earlier it was Summers who urged aggressive bank nationalization and failed to persuade the president to overrule Geithner. Christina Romer anchored the left flank of the team in demanding more aggressive action against unemployment, but by the same token was among the most skeptical about the wisdom of pushing for a major expansion of the welfare state in the middle of an economic crisis. Peter Orszag was just the opposite.

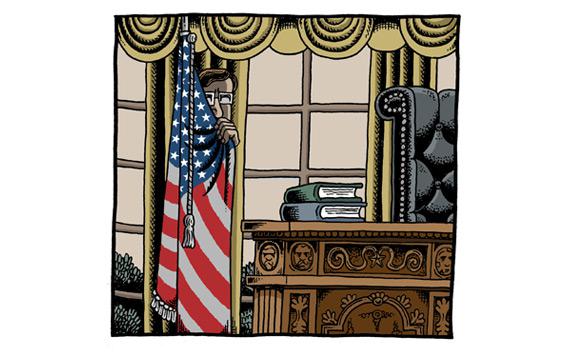

Perhaps the most revelatory detail Scheiber presents is that the most important member of the Obama economic team was Obama himself. There’s no one Svengali moving behind the scenes; there’s instead an authoritative portrait of a president and his efforts to balance competing considerations.

Time and again, many of those considerations turned out to be political. Administration economists had varying ideas about fiscal stimulus, but the conversation stopper was that “Emanuel and the other operatives were convinced that any stimulus approaching a trillion dollars was hopeless” politically. They may have been right.

Later, contemplating the idea of boosting the economy with a big-picture fix for underwater mortgages, “Summers couldn’t shake the anxiety that the only way to solve the problem once and for all was to bite the bullet and spend $500 billion to $1 trillion bailing out homeowners.” But, again, feasibility reared its head. Austan Goolsbee, contemplating the same issue, “just didn’t see how the administration could pay a $750 billion price tag to fully address the problem.”

The longest thread in Scheiber’s narrative details the administration’s misguided, premature shift of focus off job-boosting stimulus and onto the budget deficit in 2010 and most of 2011. Scheiber especially chides Orszag for undue emphasis on the debt issue, but he ignores the fact that Orszag differed from others on the economic team in a fairly nuanced way—he favored stimulus paired with deficit reduction rather than two separate political and legislative tracks.

So why did the president spend most of his first term on a futile effort to secure a bipartisan deal on long-term debt, rather than focus on the short-term jobs crisis? Scheiber suggests that one factor was Obama’s own historical sense of mission. Told by Geithner that preventing a second Great Depression would be his signature accomplishment, Obama replied, “That’s not enough.” This determination to go big got the country health care reform but failed to deliver progress on climate change and left deficit reduction as a possible source of big-picture bipartisan compromise.

The other was a strain of political advice verging on malpractice.

Aides assumed, incorrectly, that while wending its way through Congress the original stimulus would grow, not shrink. Underestimating the potency of anti-stimulus arguments, they drastically overestimated the ease with which they could come back for more should the economy prove to need an additional boost. Most of all, they insisted on taking the public’s professed concern with the deficit literally rather than as a symptom of discontent with the overall economy. Scheiber describes David Plouffe’s bizarre belief that, though proposing cuts in widely popular programs like Social Security and Medicare might “enrage” the Democratic base, “the political upside with the rest of the country would more than make up for it.” In fact, moderate voters like those programs every bit as much as Democrats, and as negotiations dragged on in Washington, the labor market limped forward and Obama’s approval ratings kept sinking. By October of last year, when the administration returned to job creation, Plouffe had changed his tune, telling his colleagues that “the president’s approval rating on the economy is tied to the economy itself”—but this was weirdly late in the game for such a banal point.

The greatest question about Obama’s economic policies, however, isn’t why the administration made the choices it did. It’s why some ideas don’t seem to have been considered at all. The flubs of Obama’s economic advisers seem to have as much to do with their failure of imagination as with any disagreements that raged between them.

Why was there no effort to tie either the first stimulus or the later payroll tax to objective economic circumstances? Did anyone mention to the president the wacky—but apparently true—fact that he could have ducked the entire debt ceiling debate by ordering the Treasury to start minting $1 trillion platinum coins? How did an administration that knew perfectly well it was facing a housing-finance crisis not manage to get a regulator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac confirmed?

Most of all, given the crucial role of central bank policy in combatting recessions—especially in the face of congressional intransigence—why was so little consideration given to replacing Ben Bernanke, and why have vacant seats on the Federal Reserve Board lingered for so long? These issues apparently didn’t even result in meetings memorable enough to blab about to an enterprising reporter like Scheiber. Now they look like some of the administration’s biggest missed opportunities.

Here, though, may be where the deficit-mania did its greatest damage. The White House is a busy place, and each hour people spent pondering doomed debt-reduction strategies was an hour not dedicated to thinking creatively about the immediate economic crisis. If the past few months of decent jobs growth keep up, Obama will likely be re-elected, his team will claim vindication, and Scheiber’s book will seem moot. But it’s not; it provides a template for future administrations—even a future Obama administration—to avoid the trap of thinking too narrowly and too politically in a crisis.

But if the jobs disappear, and Obama can’t recover? Then Scheiber’s book offers an excellent starting point for the recriminations to come.

See all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.