I hadn’t known that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis pronounced her own name in the French way: zhack-LEEN. Nor that in 1957 Susan Sontag left her husband and young son and took off for a year-long, super gay Paris love affair, nor that Angela Davis was engaged briefly to Manfred Clemenz, a handsome German exchange student. Gossip is one of the key pleasures—but far from the only one—to be found in Alice Kaplan’s absorbing new book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis.

Some American students of French see the language as a desirable way of representing and expressing themselves—perfecting themselves, even. Others see French as a way of broadening their understanding of the world outside, or a ticket into the life of the mind. For two of Kaplan’s three imposing subjects—as for Kaplan herself, as she described with candor and charm in her earlier French Lessons—the former purpose seems to have been paramount, as French offers a way of instantly remaking oneself.

by Alice Kaplan

University of Chicago Press

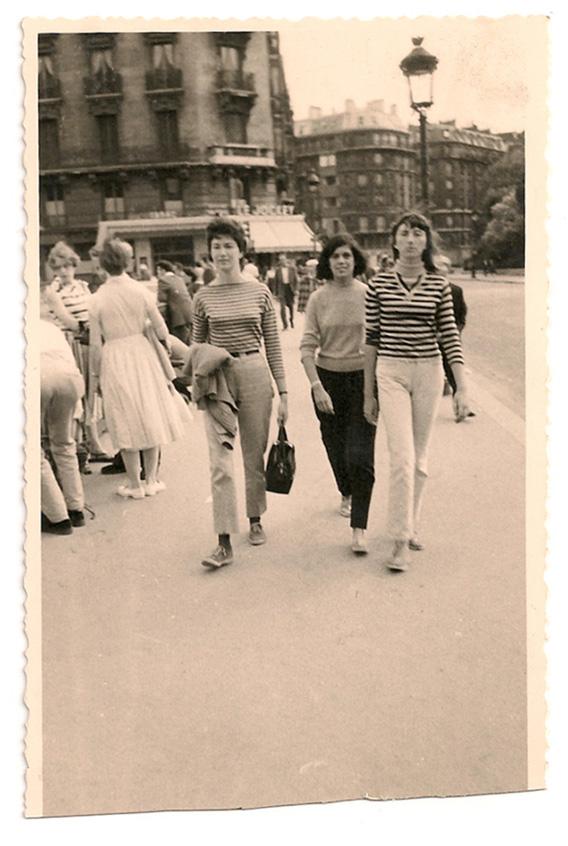

All three of Kaplan’s subjects spent a student year abroad in France; the book traces the influence of French language and culture on these soon-to-be-world-famous fabulosas. Light and fun as it is to read, Dreaming in French flirts, in appropriately Gallic fashion, with deeper questions: Why is the study of French connected so deeply in the American mind with sophistication? Exactly what is missing in American culture that our young women sought (and continue to seek) in France? (I say “young women” because the vast preponderance of French majors at American universities are women—a consistent 80 percent over the last two decades, according to David Laurence, director of the Modern Language Association’s Office of Research.) Kaplan took a tentative stab at answering these questions in French Lessons. “Why do people want to adopt another culture? Because there’s something in their own they don’t like, that doesn’t name them.” This remark suggests a deep-seated personal insecurity or “cultural cringe,” a dissatisfaction that knowing French might somehow resolve.

There is a huge divide between what Americans think of the French language and culture and what is experienced in that ancient and ever-evolving country by its natives. There’s a lot to be learned from fantasylands, though: from the chinoiserie of the Brighton Pavilion as opposed to real Chinese architecture, or from exported Hollywood ideas of America as opposed to the real thing, or from the romanticizing of young Americans in Paris.

Even now, French film, literature, and culture are touchstones of sophistication, signifiers for Americans between one another of something formal and elegant, something outside our own ways. (They also signify snooty, un-American superiority, but even that code acknowledges something in the traditional positions of the two cultures.) A familiarity with the films of Godard. To say Huis clos instead of No Exit. And the French fantasy of America and the American fantasy of France join to form an interface through which the two cultures connect.

I, too, was once a French major, visiting France for the first time the summer after high school. I was as dazzled by the beauties of Paris as any American teenager could be; I immediately bought a black beret and took to smoking Gitanes (cough), yakking in cafés, and drinking rough red wine like a native, or so I hoped. But never did I feel that French, or France, was something to escape to, as Kaplan and her subjects seem to have done. My beau idéal for France was to understand French movies and French phrases in English classics. Also, menus. By contrast, Jacqueline Bouvier fled a dull, stultifying upper-class upbringing for Paris; she wanted to be more than Queen Deb. Sontag was apparently feeling pressure to live as a heterosexual, an obligation that promptly deserted her once she arrived in France. The brilliant Angela Davis was always going to leave racist Birmingham, Ala.

So what I found most striking about Kaplan’s book was its relation not to France, but to America. It’s a book, to some extent, about the desirability of abandoning or attenuating one’s Americanness. “I am very attached by temperament to the status of the foreigner,” Sontag said in a French radio interview. “Even though I live there, I don’t feel like a New Yorker.” And there’s this really hopeless note that Jacqueline Kennedy wrote to Oleg Cassini on the eve of her husband’s inauguration:

Put your brilliant mind to work for a day—Coats—dresses for public appearances—lunch & afternoon that I would wear if Jack were President of FRANCE—très Princesse de Rethy mais jeune.

“Well, at least she didn’t say King!” quips Kaplan.

Each of Kaplan’s subjects could be said to represent a different aspect of American ideas of France: Jacqueline Bouvier, brought up in wealth and privilege, embodies the love of French aestheticism, of social elegance, art and fashion; Susan Sontag, so haughty and self-regarding, the unabashedly lofty cerebralism of the French intelligentsia; Angela Davis recalls the soixante-huitards, the idealism and intensity of the Parisian political left of the postwar period and by extension, of the modern European left that those years engendered. (Indeed, Davis soon left Paris to study with Adorno in Germany.)

Kaplan’s attempts to paint Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis as an intellectually gifted woman are belied by a hundred little details she reports herself, like this tart jibe from Olivier Todd’s biography of Malraux: “She’s good at talking about books, even the ones she hasn’t read.” There are excerpts from her essays for a Vogue competition; there’s a paragraph from a book she edited at Doubleday. All are striking in their lack of originality or interest. France, for Jacqueline Kennedy, was like a beautiful dress or a carefully-put-together room: Something you pose in.

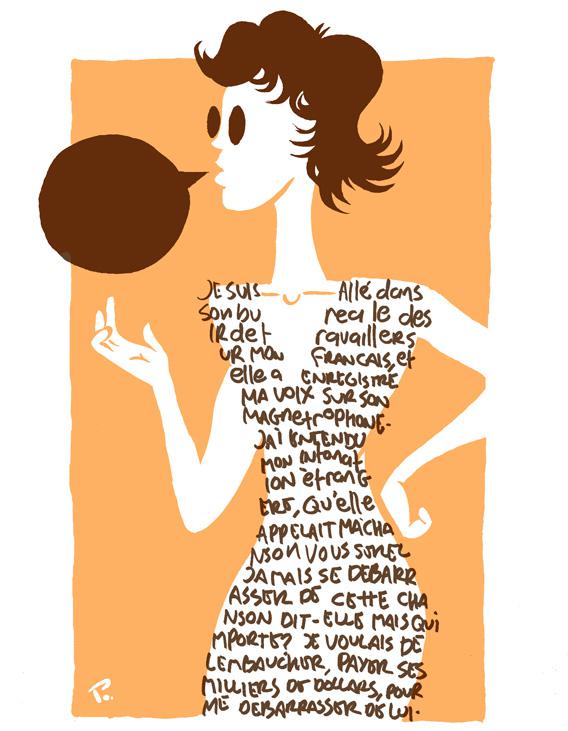

Sontag, too, seems a titanic poser. In this 1979 Apostrophes interview cited in Kaplan’s book, Sontag is joined by the likes of Robert Doisneau and Helmut Newton in a conversation about photography. Weirdly, Sontag claims that a camera is like a passport into people’s private lives; that you grant them importance by taking their photographs, so they let you right in. The panelists express a little well-bred skepticism. Well, she replies, perhaps the French have a more difficult character than do Americans, who are extremely docile and flattered around a camera. “And are you flattered when people want to take your photo?” comes the friendly but pointed question from presenter Bernard Pivot. “I’m embarrassed,” Sontag responds girlishly.

Where Kaplan sees reverence toward Sontag in this interview, I see an agreeable willingness to sock it to her on the part of her French interlocutors. Perhaps Kaplan’s earlier work as a historian (on collaborators and Holocaust deniers in postwar France), very serious in character, led her to take it pretty easy on Sontag and Onassis, whose chief crimes were dingbattery and pretentiousness.

Davis is by far the most fluent and most vital of the three. Just watch her speaking French. She had a point to make which had nothing to do with making herself seem smart or cool or beautiful or elegant or the greatest speaker of French, even. And yet Davis is all of these things. The intensity of her desire to understand, and to make herself understood, is transcendental. “A political thinker and an analyst of society, Angela Davis considered her individual adventure important only in the way it might illuminate society,” Kaplan writes. In any language the immediacy of what a person has to say will surmount whatever obstacles her questionable vowels might put in the way. Because it is not a matter of pruning one’s character as if it were a bonsai. Real language happens when there is someone to speak and someone to hear.

If this pleasurable book never quite convinced me of the story it wanted to tell, maybe that’s just because my experience is so markedly different from the author’s. And that’s totally okay. Perhaps Francophilia itself, the dreaming in French, is largely inexplicable, like the charm, impenetrable to some and irresistible to others, of foie gras, or Foucault. Maybe the mystery should be left as a sophomore French major I know left it recently, when she was asked, why? Why French? And she replied, “Je ne sais pas, quelque chose m’a pris.” I don’t know, something just took hold of me.

See all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.