In Gods Without Men, the fourth novel by English novelist Hari Kunzru, a hedge fund manager takes his protégé, Jaz, to the Neue Gallerie in New York to show him a silver coffee set made by the Wiener Werkstätte. “There’s a tradition that says the world has shattered,” he tells Jaz, “that what was once whole and beautiful is now just scattered fragments. Much is irreparable but a few of these fragments contain faint traces of the former state of things, and if you find them and uncover the sparks hidden inside, perhaps at last you’ll piece together the fallen world.”

The manager implies that perhaps the coffee set is one of these fragments with the hidden sparks. But he could also be talking about Gods Without Men itself, a novel with chapters like scattered fragments, which go backward and forward in time, each containing echoes, sometimes faint, of the others. The book is populated with spiritual seekers from four different centuries, all of them drawn, for one reason or another, to the Mojave Desert in Southern California.

by Hari Kunzru

Knopf

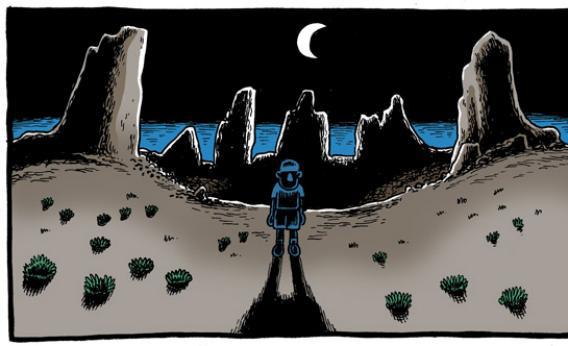

If Kunzru’s novel has a central story, it belongs to Jaz (short for Jaswinder) Matharu, the son of Punjabi immigrants, and his wife Lisa, a Jewish woman from Long Island who worked in publishing before their son was born. That son, named Raj, has been diagnosed with severe autism, and the difficulty of raising him has strained the marriage; when we first meet the couple, they’re on a “healing vacation” near Joshua Tree National Park. When they finally visit the nearby desert, they come upon a formation called the Pinnacle Rocks. And there, Raj disappears.

The riddle of Raj’s vanishing propels the novel, but around it Kunzru wraps three or four enigmas and a history lesson. The book does not begin with Jaz and Lisa but with a cryptic, American Indian-inspired prologue, and then a chapter about Francisco Garcés, a Spanish monk who really existed and kept a daily record of his 1775 trek through the Mojave. Kunzru concocts for Garcés an encounter near the rocks with “an angel in the form of a man with the head of a lion,” making him the first in a series of desert visionaries that also includes a 19th-century Mormon moving west in search of silver and a 1940s engineer seeking succor for the despair he feels at his partial responsibility for the bombing of Hiroshima. This latter figure, called Schmidt, thinks aliens will someday arrive and teach us how to be good; he hooks up with a would-be guru who attracts a hoard of UFO chasers and, in their wake, a hippie commune. All these seekers gather around the Pinnacle Rocks, which bear some family resemblance to the monolith in Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. (One of the novel’s epigraphs is a line from that book.)

These shards of stories, all chronicling efforts at mystical understanding, seem to reflect each other, the visions within prompted somehow by the blankness of the desert. Other characters look not for mystical understanding but scientific knowledge—and Kunzru seems, if anything, even more skeptical of these folks. Consider Deighton, an anthropologist who comes to the desert in 1920 to study the Indians and their culture, and who gets a few chapters of his own. Deighton regards the Indians as “primitives” and obsesses over their “purity.” He seems no freer from the colonial mindset shared by Garcés, or the Mormon miner, who each hope to convert the Indians.

American imperialism continues, of course: Today, the Mojave Desert is the site of ersatz Iraqi villages built by the U.S. military to train its soldiers in urban warfare. Iraqi-Americans, some of whom fled their homeland after it was invaded by the United States, play the natives in these simulations. Gods Without Men gives a long chapter to one such refugee, a teenage goth whose father was murdered in Baghdad. One night, during a training session, she spots Raj wandering alone in the middle of this imaginary Iraq.

How did he get there? Kunzru seems less interested in providing an answer than he is in investigating the many ways we might begin to construct one. Raj’s absence is a void not unlike the desert, and calls out for a story, not only about where he’s gone, but why. Before his reappearance, Jaz and Lisa quickly blame themselves, and each other. The American public, meanwhile, alerted to the story by TV news and the Internet, “begin to blog and tweet and post comments” about the Matharus, inventing their own theories and explanations. Kunzru, a former staffer at Wired, includes Internet comments, with aptly chosen typos and grammatical errors, in the narration, along with snippets of dialogue from the Matharus’ television appearances.

There is no straightforward solution to the mystery, but little clues and allusions send the reader back to that cryptic prologue, a faux-Indian folktale about Coyote. That trickster figure reappears periodically throughout the novel, sometimes as an animal—one howls just before the Mormon miner has a vision of angels and airships; another whines before Schmidt, the engineer, sees alien spacecraft—and sometimes in human form. One of the hippies who arrives in the wake of Schmidt is named Coyote; he’s still living in the area when Jaz and Lisa arrive on vacation.

In a tutorial of sorts about the Coyote legend, we learn that Coyote can move back and forth between the land of the living and the Land of the Dead. This suggests a supernatural explanation for both the disappearance of Raj and a parallel mystery that emerges in the chapters about Deighton, the anthropologist. Deighton one night sees a white child who appears to be glowing walking with an Indian man named Mockingbird Runner. When he tells this story in a nearby town, he prompts an investigation cum lynch mob: Angry white men chase Mockingbird Runner to the Pinnacle Rocks, where he is either killed or, perhaps, trapped in the Land of the Dead, whence he emerges to snatch Raj in 2008, only to return the baby to the land of the living a few months later in the middle of that military simulation.

Admittedly, I am still puzzling this out. Gods Without Men is a shaggy, multi-tentacled beast of a book, with many of its parts cast in shadow; that Kunzru could cram so much detail and plot into less than 400 pages is some kind of miracle of compression. (I haven’t even mentioned the British rock star, the meth dealing, the echoing instances of adultery across generations.) The book engages with enormous, complicated themes: religion vs. reason, indigenous culture vs. imperialism, fact-finding vs. storytelling. And Kunzru is a fiercely intelligent writer, who exhibits remarkable control over both his material (he has done prodigious research) and his impressive variety of narrative voices (he has negative capability in spades).

But I admire Gods Without Men more than I enjoyed it. In a recent Paris Review interview Ann Beattie said that “when you write fiction you’re raising questions, and a lot of people think you’re playing a little game with them and that actually you know the answers to the questions.” Kunzru does not pretend to have the answers in this novel—but he does play a game of sorts, burying hints and allusions you must hunt for if you want to figure out what could possibly be going on. His approach befits the trickster, Coyote, who seems to serve as a kind of spirit guide, and who, like Kunzru, probably doesn’t care that I might have liked this story better if he’d told it straight.

See all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.