A vast gulf separates us from the incidents described in Ellen Ullman’s new novel By Blood: a gulf the approximate size and shape of the Internet. The pieces of technology that matter in By Blood’s San Francisco-circa-1974 feel positively antediluvian: the sound machine that masks the therapy sessions taking place in the office next door to our narrator (a disgraced professor facing sexual misconduct charges) but that’s periodically turned off at the request of one patient, on whose sessions the narrator compulsively eavesdrops; the reel-to-reel tape recorder the patient takes with her to Israel late in the novel to record conversations with her newly discovered birth mother. Subsidiary machines make an appearance now and again: Radio broadcasts inform the narrator about the oil crisis and the Zodiac killings; the narrator rides the streetcar; other motor vehicles impinge on his awareness. But By Blood’s treatment of identity has more in common with the milieu of classical tragedy (Electra wondering what’s happened to Orestes, Oedipus blithely unaware of the identity of the man he killed at the crossroads) than with the world of Facebook, where reunions with lost family members are as simple as clicking “Friend”—hardly the stuff of drama.

by Ellen Ullman

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux

Covering some of the same ground as Woody Allen’s 1988 film Another Woman, a pioneer in the depiction of therapeutic eavesdropping, By Blood shows the narrator falling deep into the drama unfolding on the other side of the door, convinced that he has come in on the patient’s therapy “at just the right moment, one of those mysterious fulcrum points: a pure, Aristotelian shift in the plot wherein the therapeutic story of the patient’s life was about to turn.” We learn neither his own name nor that of the object of his obsession; he likens his contextless experience of the situations she describes to tuning in “to a radio play, a disembodied story floating in the quickening of my imagination.”

The nameless and faceless patient is a Midwestern lesbian financial analyst, adopted, about to embark on a quest to discover her birth mother’s identity—a quest in which the narrator himself will become dangerously and inappropriately entangled. (If only he had access to Google: the few details he possesses about this young woman’s traits—her age, her Wharton MBA, her profession—would undoubtedly provide enough information to let him see her name and a profile pic!) His own family tree is dotted with suicides, and he’s long been preoccupied with the fantasy “of the self-created individual, freed from the ownership implied in the inheritance of one’s parents’ genes: You are not of them; they do not own you; you owe them only the normal gratitude for having been raised up and fed by them; you may become what you need to be.”

The narrator does possess the name of the psychotherapist, but he knows little beyond the bare fact of her professional qualifications and her German origins. He tries to catch the patient in the hallway to the office building, but is frustratingly unable to determine which one of several young women she might be. The uneven conditions of ignorance in which he is forced to remain—knowing a good deal about the patient’s inner life but nothing much at all about her appearance or worldly identity—are an enabling premise of Ullman’s drama. When the patient drops an envelope in the lobby, a letter meant to be forwarded to her ex-girlfriend, the narrator learns not her name but only her street address, a stalkerish development that lets him become even more involved in facilitating her investigation into her past.

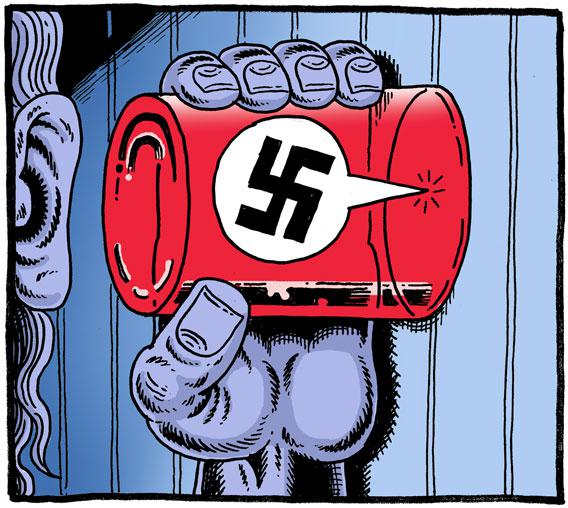

Assisted by the narrator’s discreet and creepy stage management, the patient’s inquiry will lead her to a group of Jewish orphans at Belsen in the last days of World War II. In Israel, the patient will also encounter something like a parallel self, an unsuspected sibling—also adopted—whose story of her own reunion with their mother casts light on the terrible meaning not just of why the patient was given up for adoption as a baby but why her mother never sought her out later on.

At precisely this juncture, though, the narrator’s own fatal involvement in the story’s uncovering comes to light; the sound machine is turned back on and the curtain falls, sundering the narrator from the protagonist with whom he has so thoroughly identified and leaving the reader in equal parts unsettled and moved. It seems that intimacy and identification can take us only so far, and that fate is determined to throw us back on our own resources, depriving us of the comforts of recognition and discovery. Ullman’s best-known book probably remains her first, a 1997 memoir of her career as a programmer in the 1970s and 1980s. (She has also served as a commentator on technology for NPR, the New York Times and many other venues.) Close to the Machine: Technophilia and Its Discontents is a series of short essays on topics ranging from the conceptual allure of the spreadsheet to the difficulty Ullman experiences letting go of a now-obsolete small white spiral-bound notebook that contains the UNIX operating system in its entirety.

The memoir’s overarching narrative, such as it is, chronicles the generational incomprehension that separates Ullman and her younger male lover, who cannot understand Ullman’s attraction to the past any more than she can comprehend what drives him and his ilk to want to make money rather than things, to look for satisfaction in growing a company rather than, say, getting a Ph.D. or learning French. Her own love for the kind of work engineers do, though, her satisfaction with being part of a group of “people who built things and took our satisfactions from humming machines and running programs,” comes sometimes at the cost of personal intimacy and an investment in private life.

What is most distinctive about Ullman’s voice in both these books is the way it sounds fully formed, mature both intellectually and emotionally; the books themselves read as seamless constructions that so thoroughly and elegantly survey the terrain at hand that they don’t seem to want to be talked back to. This is more a strength than a weakness. The narrator of By Blood, shut literally out of the conversation that obsesses him and existing at several removes from the story in which he is interested, in this sense models the position in which Ullman places her reader. We too press our noses up against the glass of this alienating, addictive novel. The story on the other side repels intimacy as much as it elicits it.

See all the pieces in the new Slate Book Review.