This August I’m hosting a literary interview series at Edith Wharton’s country estate, the Mount, and as the date draws near I find myself wondering what the grande dame herself would think of such an enterprise. My hunch is she’d have mixed feelings.

When the novelist and her husband, Teddy, moved into their just-built mansion in Lenox, Massachusetts, in 1902, the locals wondered if Wharton would become the new Catharine Sedgwick, the best-known female novelist of the 1830s, who’d maintained a literary salon in town. The Berkshires had long been lousy with writers. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and William Cullen Bryant had lived in the area. The famous first meeting between Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne took place in 1850 on nearby Monument Mountain; for the next two years, they lived 6 miles apart. After Hawthorne died in 1864, tourists flocked by the hundreds to the little red house where he’d written The House of the Seven Gables and The Blithedale Romance. Maybe Wharton’s arrival would replenish the ranks?

Alas, salon-presiding was way too art-for-art’s-sake for this pragmatist. She considered art central to civilization, a virtue to be integrated into daily life, not handled with kid gloves and kept separate. And yet, the fact that she strove with her books to reach as wide a readership as possible indicates she might be at least grudgingly amenable to literary programming taking place on her property. In our era of disappearing libraries and bookstores, author appearances are a vital way to keep literature alive in the public eye. (Also, there is the more gauche matter of keeping alive the Mount itself, now that she’s no longer here to fund it.)

I’ve long admired the Mount as a rare instance of an “autobiographical house”: Wharton designed it herself, according to the architectural principles she set forth in her first published book, The Decoration of Houses, and closely oversaw its construction. Only now am I appreciating her gifts as a hostess. Wharton was a social woman, and it was here, far from the fashionable Newport resort scene she’d grown up with, that she was finally able to reject the highly regulated yet completely mindless fraternizing of her privileged class—endless afternoons spent “paying calls”; suffocating weeklong house parties requiring countless changes of dress and vapid dinner-table conversation—and entertain on her own terms.

Wharton wasn’t merely in pursuit of the so-called good life; she was out to master what she called “the complex art of civilized living,” an elegant balance of work, art, and leisure. She built her value system directly into the estate, which is something of a live-work space writ large. All through the summer and fall, she’d host a steady stream of houseguests without putting a dent in her own productivity.

“I need scarcely tell you that I am very happy here, surrounded by every loveliness of nature & every luxury of art & treated with a benevolence that brings tears to my eyes,” wrote the famously fastidious Henry James to a friend during a stay at the Mount in 1904. In another letter, he assures his correspondent, “You needn’t bring supplementary apples or candies in your dressing bag,” adding that the Whartons are “kindness and hospitality incarnate.”

Photo by Kevin Sprague/the Mount.

Happily for American literature, sadly for those of you who own summer houses and we who visit, Wharton didn’t follow up her decorating guide with one on entertaining. And so, after consulting her biographies and interviewing Anne Schuyler, curator and house manager at the Mount, I’ve come up with my own: I’m calling it The Hosting of People. Wharton may have been born into the original 1 percent—it’s said her family inspired the idiom “keeping up with the Joneses”—but even those of us without the means to summer on her scale can mine great entertaining lessons and best practices from her approach. (I’m especially looking forward to channeling her genius for scheduling the next time I go in with friends on an Airbnb house rental.) I think I’ll use the following, said by her friend the printer Daniel Berkeley Updike (no relation to John, that I know of), for the blurb of my book:

“I do not remember any house where the hospitality was greater or more full of charm than at the Mount. As one thinks of it in retrospect, the word ‘civilised’ comes to one’s mind.”

The Hosting of People

Chapter 1: Police the Guest List

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

Only invite people you really like—otherwise there’s no point. By the time Wharton moved into the Mount, at age forty, she’d been dutifully playing society wife for 17 years. Finally, she was able to entertain whomever she wanted. She deepened her relationships with selected childhood friends, and made new ones in Lenox. As she came into her own as a novelist (her breakout book, The House of Mirth, was published in 1905), she made a point of spending as much time as possible with the many likeminded people she was meeting through her work, many of them editors, publishers, academics, and fellow writers like James, a frequent, favorite guest.

Wharton was undeniably class-bound, but also, biographer Hermione Lee points out, always open to new possibilities. She seems to have had a fondness for quiet, introspective types, and she never saw age as a barrier, for instance befriending both the distinguished social critic Charles Eliot Norton and his devoted daughter Sally. So: Weed out the people you don’t care about, preserve time for the people you do, and take advantage of the opportunity hosting presents to cultivate new friendships with those who cross your path who seem interesting.

Chapter 2: Keep It Small

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

Wharton designed the Mount expressly for small-scale entertaining, not for show or big parties, the raison d’être for the Newport resort scene she’d left behind. She preferred her visitors to come two or three at a time, for a mix of long and short stays (from several days to several weeks, depending). For her, the point of being around other people was to indulge in the kinds of long, wide-ranging conversations only possible in intimate groups. The same went for her dinner parties back in the city. When the decorator Elsie de Wolfe asked her why her dining table only sat eight, Wharton replied, “Because there aren’t more than eight people in New York I care to dine with.” (Of course, that remark doubles as an entertaining principle and Wharton’s attitude toward America in general, which she left for good in 1911.)

Chapter 3: Comfort Is in the Details

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

A staff of nine certainly takes the chore out of hosting, but Wharton’s attentiveness to the little things is easy enough to replicate by the rest of us. When her guests arrived, tired and dusty from their train journey, she liked to greet them with Champagne. Turning off the lights and brightening the evenings with wax candles ensures the living room doesn’t “look like a railway-station, the dining-room like a restaurant,” as she wrote in The Decoration of Houses. Judging by James’ note about the apples and candies, she kept plenty of snacks on hand to nibble between meals. I’m especially charmed by the heart-shaped hooks she installed only in the guest rooms (presumably crafted in the nearby Shaker village)—a small touch that shows your guests you’re thinking about them.

Chapter 4: Schedule Lots of Me Time

Photo by John Seakwood/the Mount.

Central to Wharton’s entertaining philosophy was plenty of time for herself, which ensured she got done what she needed to do and, when finished, could be fully available to her guests. On a typical day at the Mount, she rose at 6 o’clock and ate a light breakfast of coffee and rolls while sitting in bed reading the newspapers and writing. Around 11 o’clock she’d end her workday and walk the grounds with her gardener. Nobody was allowed to interrupt her, ever (except the servants).

Chapter 5: Dine Alfresco

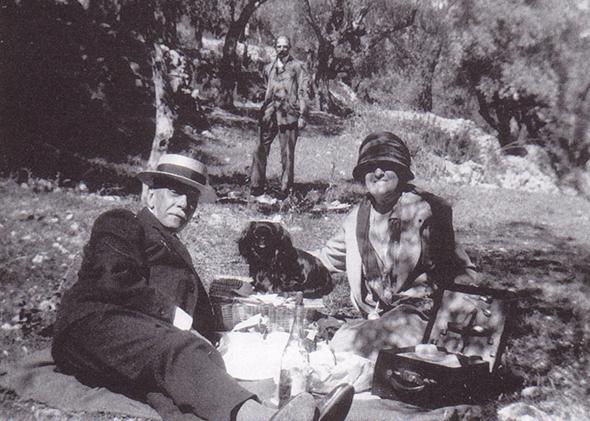

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

At noon Wharton convened with her guests for lunch on the terrace, or even better, picnicked with them somewhere on her gorgeous grounds (designed with help from her niece, the noted landscape architect Beatrix Farrand)—a wonderfully casual retort to the multiple-course luncheons of her youth. Given her appreciation for common-sense solutions, I think she’d understand swapping out her own cumbersome picnic basket—surely carried by a servant—for one of today’s ubiquitous canvas tote bags, kept stocked and at the ready with a blanket, a corkscrew, and dining utensils.

Chapter 6: Be Adventurous

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

Vacationers fall into one of two groups: those who like to get out and do things, and those who don’t. The ever-industrious Wharton didn’t leave much room for choice, perhaps rightly intuiting that even bookish types—make that especially bookish types—need to stretch their legs. She made sure that every afternoon held an outdoor excursion of some stripe—long walks; gardening; horseback riding; touring in her motorcar through the countryside. A favorite group nighttime activity was stargazing.

Chapter 7: Read Alone Together

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

“Almost every day on returning from the afternoon expedition we were greeted by an engaging row of new volumes, which the hostess instantly handed over to her guests,” remembered her friend Robert Norton. Presumably, after the outdoor excursion and before changing for dinner, guests would settle in with a book on one of the many plush armchairs in the drawing room (comfort was paramount for Wharton), or a chaise on the terrace. Apparently she had something of a mania for occasional tables; you were guaranteed to always have a place at your elbow to rest your lemonade.

Chapter 8: Read Aloud Together

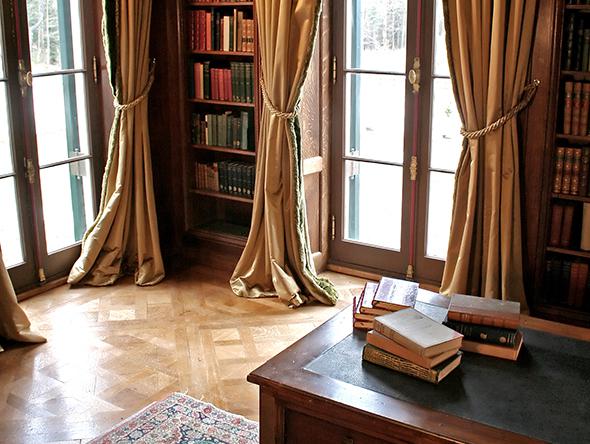

Photo by David Dashiell/the Mount.

One guest reported that sometimes Wharton would ask her visitors if they’d like to hear her read one of her own chapters in progress, and give criticism. “It helped her very much, she said, to be able to talk over what she was writing; and she encouraged us to be completely frank in our comments and suggestions.” For the after-dinner evening entertainment, everyone retired to the library to take turns giving readings—the works of Walt Whitman were a favorite.

Chapter 9: Don’t Skimp on Food

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

Sadly, little is known about what Wharton actually served at her table—I won’t be following up this entertaining guide with a cookbook. But it’s known she “liked rich and choice food and a good deal of it,” as her friend Gaillard Lapsley put it. At breakfast there were homemade marmalades and jams, and teatime was caravan tea from China, honey, and scones. One guest remembers a lunch of “rice and chicken’s liver, then a roast chicken of the tenderest, peas, and strawberries and cream.”

Dinner was probably at 8 o’clock. Though everyone who visited the Mount raved over the food, they tended to be less specific than later visitors to Sainte-Claire du Château, her eventual home in France. There’s been reference made to “lobster a l’Americaine” combined with fillets of sole, as well as “a very good potage, grilled turbot, salsifis sauté, and apple charlotte.” Her friend Vivienne de Watteville rhapsodized: “Dinner was a poem to which brains and palate equally combined to bring a fitting appreciation; it was not a matter of living too well but whether one could bring fine enough discernment to a work of art.”

Chapter 10: Drink Well! But Not Too Much

Photo courtesy of the Mount.

It’s said sometimes that Wharton was a teetotaler, but Schuyler doesn’t think so—rather, that there was a distinction between hard liquor (which her husband overimbibed) and wine. “A good wine cellar was a mark of civilization and a point of pride in her New York upbringing, and certainly remarked upon in her fiction,” says Schuyler. She adds that Wharton’s few extant recipes (Christmas pudding; lobster dishes) called for generous amounts of alcohol.

Chapter 11: Early to Bed

Photo by John Seakwood/the Mount.

Wharton was no talk-till-dawn bohemian: She made sure that she and her guests got a good night’s rest for the morning of work to follow. Nobody knows for sure, but bedtime was probably 11 o’clock, depending on the company and the conversation. Falling asleep in that pastoral quiet was one of the Mount’s greatest pleasures. As Wharton once wrote to a friend at the end of the season, “We are in despair at the thought of leaving this delicious stillness, & warm bright sparkle of air, for the noise & stuffiness of that execrable N.Y.”

Touchstones at the Mount opens on Aug. 8 and runs for four consecutive Fridays. This summer’s featured guests are Andre Dubus III, Joanna Rakoff, Scott Stossel, and Jennifer Finney Boylan. Go to edithwharton.org for more details.